In the Margins: Ultrasociety by Peter Turchin

A Footnote on War, Violence, and Pathology in History

In this recurring series (of a sort), I will be providing additional notes and commentary to supplement those I provided in the revised, expanded edition of Political Ponerology. In some cases notes got deleted or shortened in the editorial process to avoid having too much text crowding the page or straying too far afield. In this case, I simply hadn’t read the source in question until after publication. Either way it will allow me to write some more extensive commentary using old and new sources.

The book in question is Peter Turchin’s Ultrasociety: How 10,000 Years of War Made Humans the Greatest Cooperators on Earth, published in 2016. I like Turchin’s work, and cited some of his other books (like Ages of Discord) in the notes. His empirical approach to questions of history is satisfying to read (as is his prose), and it’s nice to have in this book a solid correction to some of the errors in the approaches of guys like Steven Pinker (in The Better Angels of Our Nature), Jared Diamond (in Guns, Germs, and Steel), and Richard Dawkins (in The Selfish Gene).

A History of Violence

First a quotation from Ponerology. In the introduction, Lobaczewski points out that until recent times a book (like PP) “offering a sufficient explanation of the causes and processes” by which humanity descends into “bloodthirsty madness” (i.e. ponerogenesis) was impossible. He prefaces this by saying:

If a collection were to be made of all those books which describe the horrors of wars, the cruelties of revolutions, and the bloody deeds of political leaders and their systems, many readers would avoid such a library. … The collection would include works on the philosophy of history discussing the social and moral aspects of the genesis of evil, but they would also use the half-mysterious laws of history to partly justify the blood-stained solutions. However, an alert reader would be able to detect a certain degree of evolution in the authors’ attitudes, from an ancient affirmation of primitive enslavement and murder of vanquished peoples, to the present-day moralizing condemnation of such methods of behavior. (pp. 2-3)

Though it does not discuss psychopathology, Turchin’s book is a welcome addition, tracking the history of human cooperation and warfare from hunter-gatherer tribes through the early and complex chiefdoms, and insanely despotic archaic states, to our highly cooperative modern mega-states (“ultrasocieties”). He argues that warfare, especially new technologies (like the invention and spread of new projectile weapons), has been the main driver of cultural evolution throughout the past 10,000 years, and the main driver behind the transition to large-scale societies—not, for example, agricultural productive capacity (per Diamond). Similarly for the observable decline in violence over the past several thousand years—not a result of modern Enlightenment values (per Pinker).

Humans are a cooperative species, but not always and not with everyone. Effective hunting of large game required individual hunters to cooperate in groups—much more effective than a collection of hotshots each trying to take down his own mastodon. Now what about an invading tribe? Combat with other groups fosters and requires cooperation both for defense and offense. And as resources became more valuable (e.g. permanent, settled agricultural villages), the need for better defense became paramount. Part of the answer: form alliances. A bigger group of fighters stands a better chance than a small one.

Notice what this implies: as the group grows, warfare may become more intense on the peripheries (with armies as opposed to small collections of warriors), but the number of people not at war greatly increases—fighting occurs on the frontiers, not deep in the heartland, which knows relative peace. The people within the new, expanded “tribe” (a collection of villages, a tribal alliance, an early chiefdom, an empire or mega-state) all cooperate on a level previously unknown in human history. The circle of cooperation expands from a close kin group to include strangers, previously the most potentially dangerous type of person there was. Whereas with intertribal warfare there are many small “circles” engaged in almost constant combat, with the risk of being wiped out, now the circles are larger, and those within them safer than their smaller progenitors were.

In the process, smaller and less internally cohesive tribes or villages get wiped off the map and the survivors are the larger social units—themselves internally cohesive, though externally combative. As Turchin puts it, “the evolution of cooperation is driven by competition between groups.” And to succeed, “cooperative groups must suppress internal competition [e.g. by moralistic punishment]” (p. 93).

Before reading Turchin I wasn’t aware just how violent inter-tribal (pre-agricultural) warfare really was—a state of almost constant warfare with violent death dozens or hundreds times more common than it is in even the most violent countries today. Nor was I aware just how widespread was the despotism of archaic states (which first appeared some 5,000 years ago, but developed and existed in some locales up to relatively recent times, e.g. Hawaii in the eighteenth century).

Upstart Alphas and God-Kings

Lobaczewski writes:

Our zeal to control and fight anyone harmful to ourselves or our group is so primal in its near-reflex necessity as to leave no doubt that it is also encoded at the instinctual level. This is a result of the fact that retaliation was originally a necessity of life. Our instinct, however, does not differentiate between behavior motivated by simple human failure and behavior performed by individuals with pathological aberrations. (p. 28)

This also includes “upstarts” and free riders—those who shirk their hunting duty, for instance, or who get a little too big for their britches and try to elevate themselves and boss others around—wannabe despots. Humans have always been very good at detecting such people and taking them down a peg or two. In cases where gossip, ridicule, or ostracism (or even just ignoring their orders) didn’t work, we always had a last resort: homicide. And it didn’t matter if the upstart was the strongest among us and could easily defeat us in a fight. We had a solution: projectile weapons. First stones, then spears, bows and arrows. Anything to put some distance between us and a potentially physically stronger foe and give us a fighting chance. (David and Goliath are archetypal in this regard.)

As Turchin puts it, projectile weapons were the first “equalizer” of humanity: “Lethal weapons drove the evolution of egalitarianism, thanks to our collective ability to control and subdue aggressive, physically powerful males” (p. 108). That and our ability to form coalitions. The result was a “reverse dominance hierarchy” based more on persuasion and consensus-building than physical domination.

This changed after the development of agriculture, followed by that of the first archaic states. Alpha male upstarts made a comeback in the era of the god-kings. It took an average of around 5,000 years, or at least 100 generations, for archaic states to appear after the development or introduction of agriculture in a particular region, once populations passed the tens of thousands and approached hundreds. Resistance to upstarts (primarily from within the military) was successful for all that time, but eventually the growing polities succumbed.

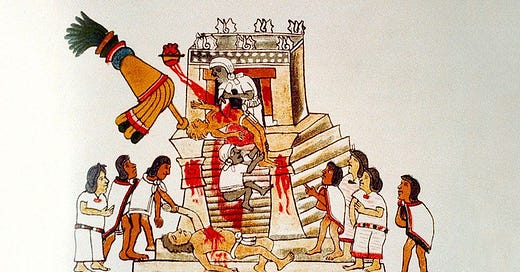

Archaic states shared a lot of features, most notably extreme inequality (the elites owned all the land and did no work, demanding tribute, labor, and wives from the commoners), but also divine kingship, slavery, and frequent human sacrifice. War and ritual were central. The god-king must be provided with a form of spiritual energy (mana in Hawaii) continually in order to preserve the cosmic order, which he embodied. Any commoners who failed to perform the correct religious genuflections, for example, were executed on the spot. Periodic executions of those least compliant seem to have selected for populations with an excellent capacity for internalizing (religious) rules. Do what’s expected of you, don’t question, don’t stick your head out, or you might lose it.

But, Turchin asks, if we were so effective at countering upstarts prior to the emergence of states, what gave? How did all archaic states swing so far in the other direction? He criticizes most existing theories on empirical grounds and proposes his own: successful military alliances (formed in response to the constant threat of warfare), the Machiavellian appearance of legitimacy buttressed by supernatural/ritual power, and eventual takeover by a god-king in whom is held all military and religious power. (He provides Augustus as a possible, though late, model—after so much war and destruction, the commoners will gladly accept a god-emperor if it means peace and stability, especially if he makes a show of being modest and not arrogant.)

The Era of Pathocracy?

The progression of violence and inequality over human history hasn’t been a straight line from violence to peace, as Pinker suggests. Rather, it’s Z-shaped.

I think the missing ingredient in understanding the archaic states is … you guessed it: psychopathology. Combine constant warfare (which may select for some psychopathic traits), poor nutrition (n.b. Turchin credits the Paleo diet with turning his health around), and probably a whole lot of right-frontal lobe brain trauma in utero and in early childhood, and you have a start. (I consider Adrian Raine’s The Anatomy of Violence the most important book on this particular subject.)

But also note how Turchin thinks the first god-kings ascended to power: not on their own, but through a “coalition of upstarts” (pp. 160, 178), a coup consisting of the military/ritual leader and his loyal retinue and warriors. In other words, a ponerogenic association. It wasn’t just groups of selfish elites who took power (all elites are selfish—it’s the iron law of oligarchy). The archaic states and the elites who ruled them were the stuff of nightmares and seem to stand out from all the rest. Our modern pathocracies strike me as a best-effort attempt to recreate them, but limited to a large degree by our “post-Axial” norms.

Axial Transitions

After the archaic states came the mega-empires (e.g. the Achaemenid in Persia, the Mauryan in India, the Han Dynasty in China, and the Roman Empire) with vastly different ideas about human dignity. New religions and philosophies appeared: Zoroastrianism, Platonism, Judaism, Buddhism, Christianity, Confucianism, Taoism, (and later) Islam. The “universalizing, morality-focused and ruler-constraining ideologies.” The common occurrence of many of these in the mid-first millennium B.C. caused Karl Jaspers to hypothesize an “Axial Age.” For Turchin it is these religions that are largely responsible for the decline of violence and increase in cooperation Pinker observed (not reason, as Pinker would have it).

Lobaczewski saw something along these lines:

How astonishingly similar were the philosophies of Socrates and Confucius, those half-legendary thinkers who, albeit near-contemporaries, resided at opposite ends of the great continent. Both lived during evil, bloody times and adumbrated a method for conquering evil, especially regarding perception of the laws of life and knowledge of human nature. They searched for criteria of moral values within human nature and considered knowledge and understanding to be virtues. Both men, however, heard the same wordless internal Voice warning those embarking upon important moral questions: “Socrates, do not do this.” That is why their efforts and sacrifices constitute permanent assistance in the battle against evil. (p. 59)

Once civilization and its concurrent discipline of thought reaches a certain level of development, a monotheistic idea tends to emerge, generally as a conviction of a certain narrow intellectual elite. Such development in religious thought can be considered a historical law rather than individual discovery by such people like Zarathustra or Socrates. The march of religious thought through history constitutes an indispensable factor of the formation of human cultures. (p. 286)

How did warfare fit into this transition to mega-empires? Blame Conan (the Barbarian, not the late-night talkshow host). Or rather, those warriors on horseback from the Great Eurasian Steppe (progenitors of the Cimmerians and Scythians). Armed with the newly developed composite bow and iron arrowheads, cavalry took warfare to another level, forcing societies to adapt and necessitating even better defenses. Existing states were no match for the horse archers. “We’re gonna need a bigger state!” Maybe one with walls to keep out the horsemen—like China. The despotic archaic states were no match for the new multiethnic mega-empires and their massive armies, either.

Incidentally, however, after writing Ultrasociety, Turchin and his team did a study on the Axial Age (there’s an edited book too, which I have not yet read), concluding that it was not a specific time period or limited to certain regions. Rather, “‘axiality’ as a cluster of traits emerged time and again whenever societies reached a certain threshold of scale and level of complexity” (from the book description)—sometimes earlier than Axial Age proponents have argued. (See also their more recent paper on the rise of the moralizing religions.)

Now, since this post has turned out much longer than I’d planned, I’ll close with two quotations, the first from Lobaczewski, the second from Turchin. Turchin’s book provides a nice supplement to the first. And the second strikes me as very ponerological.

If we observe the throngs of people crowding the streets of some great human metropolis, we see what looks like individuals driven by their own affairs and concerns, pursuing some crumb of happiness. However, such an oversimplification of reality causes us to disregard the laws of social life which existed long before the metropolis ever did, which are still present there, although somewhat impaired, and which will continue to exist long after huge cities are emptied of people and purpose. Loners in a crowd have a difficult time accepting that reality, which exists at the very least in potential form, although they cannot perceive it directly. (PP, p. 39)

Long-term social “experiments”—attempts to impose a new morality from above—show that social norms and institutions which go strongly against human nature do note “take,” no matter how hard they are promoted. (Turchin, p. 146)

That's an intriguing suggestion. I certainly agree that organized violence plays a dominant role in the evolution of human societies. I think it's much more granular than the big picture illustrated above. Different eras with different characteristic military technologies invariably adopt different societal forms, with the primary dichotomy between centralization/decentralization or equivalently, liberty/authoritarianism.

In some ages (the Greek iron age, for instance, or the Roman Republican era) weapons were relatively easy to use and cheap to make. The result is a preference for mass armies composed of regulars, typically citizen soldiers who in many cases provide their own equipment (note that the professional armies of the Roman Imperial period were a late development). In other eras - for example, medieval Europe, in which a knight required a large quantity of expensive armour and needed a lifetime of training to use it effectively - it takes a much larger economic effort to support a single warrior, and the result is a more hierarchical society.

Back to the ancient despotisms. I'd argue that the chariot may have been the driving technology. They were invented around the right time, they weren't cheap by the standards of the late neolithic, and armies without them would have stood no chance against armies with them. The result was the development of a specialized warrior caste supported by a peasant caste (sure, the peasants would be conscripted and handed spears when war broke out, but spearmen aren't much of a threat to charioteers).

Before that era, weapons technology was relatively static - flint knives, spears, and arrows, the same as during the hunter-gather period of the neolithic. Since these were available to all, they resulted in an egalitarian society.

After the chariot era, advances in metallurgy lead to wider availability of bronze and then iron weapons. Iron was the real game changer as it's so much easier to mine and make. The result: the hierarchical societies of the chariioteer bronze age gave way to the relatively egalitarian city states of the Hellenic iron age.

The invention of the stirrup then returned the emphasis in warfare to cavalry; thus, the aristocratic warfare of the middle ages, and the hierarchical social structure that accompanied it.

With gunpowder, the musketeer and then the rifleman soon dominated the battlefield. Mass democracies were not far behind, and serfs became free-holding yeoman farmers.

The 20th century saw the development of mechanized warfare and aerial warfare, both extremely expensive weapons technologies that are far beyond the reach of individual households. Democratic republics gave way in function, though not in form, to vertically integrated managerialism ... again the pattern continues.

Extrapolating to the future, it seems the next iteration in mechanical warfare will be the drone. Drones are in principle extremely easy to use, very cheap to manufacture, and when combined with 3D printing it will be possible to make them at home. Military exercises with drone-equipped platoons indicate that they are a ridiculously potent force multiplier, enabling a formation to take a hardened objective in a fraction of the time and with a fraction of the number of men. If the pattern holds, that points to a return to a decentralized, egalitarian societal form.

>Iron law of oligarchy

Good point.

I'd add that only Autocracy can combat Oligarchy.