The Cost of Ignorance: How Gaps in Understanding Psychopathy Endanger Kids

Continuing Chapter 5 of Karen Mitchell's work

Parenting and Children

For many, direct exposure to the persistent predatory personality (PPP) starts early. Lobaczewski briefly mentions the personality-deforming effects of being raised by a psychopathic or character-disturbed parent. Not having any experience to the contrary, such children imbibe “pathological” material from a young age, instilling in them with various illusions about the world, maladaptive emotional responses, and twisted values.

Mitchell adds several of her own observations based on the responses from her study’s participants. As one put it: “the children’s needs are never put first. They [the predatory parents] always have control.” Additionally, such parents “use their children to achieve their own goals.”

This is rarely observable or visible, however, as [the parents] often invest substantial effort into appearing to be a ‘good parent’ and grooming others to believe they are committed to their children while engaging privately in behaviours that are abusive, manipulative, intimidating, controlling, harmful, and/or undermining the other parent to family and friends.

One participant knew a dark personality (DP) who “killed his child to get victory over the mother.” Another treated his child “incredibly well later in life” to do the same. These are instrumental behaviors lacking in any genuine “parental love.” Such parents do not require their children’s presence in their lives “and can go for years without seeing them. If they are ever challenged about not seeing their children for a lengthy period, they will often construct a false narrative, blaming the other parent for their absence.”

Predatory mothers and fathers “put substantial effort into destroying the child’s relationship with the other parent,” using a number of tactics like “lying; ‘reversing the narrative,’ which is to attribute their nefarious behaviours to the protective parent; criticising the other parent; making ungrounded and serious accusations against the other parent; offering financial incentives to a child; provoking the other parent in the presence of a child, and so on.” These can also include “physical violence, isolation from family and friends, threats, court weaponisation, paying people to stalk the non-DP parent.” PPPs may also harm their children through neglect or by setting their children against each other.

This imposes a large burden of time, energy, and resources on the non-DP parent, especially since that parent often doesn’t know precisely what is going on. Quoting another participant: “They are always dealing with mopping up damage, are always behind the 8 ball, always protecting, but the DP parent is turning the children against them.”

The DP parent’s behaviors can cause a litany of problems: “mental, emotional, physical, social, relational, sexual, financial, familial, and school related.” To anyone who has observed this dynamic from the outside, it’s clear that “the harm they are causing to their children through their behaviours are not as important [to them] as continuing their coercive control,” as one participant put it.

While PPPs are inherently selfish, this is not their only motivation. The behaviors listed above also involve “a level of sadistic enjoyment of inflicting harm, discomfort, and humiliation.” They also use intimidation to prevent exposure. These acts are usually performed in private, and if the child happens to confide in another adult, the PPP will vigorously deny the child’s accusations.

Several research participants commented that children often ‘back down’ when required to talk in an official context about emotional, mental, physical, sexual, or other forms of abuse from a parent who is of DP out of fear of how that parent may react …

Such children often develop their own methods of self-protection, such as running away, ensuring they have weapons close at hand (whether real or toys), and not discussing their parents’ actions for fear of retribution.

To reiterate a point above, any ostensibly loving behavior on the part of a PPP will not be motivated by actual parental love. Rather, it will be an act designed to serve another goal. Mitchell summarizes some of these goals as follows:

the ego boost of being seen as a ‘great parent,’ to harm and punish others, particularly the other parent of the children, to leverage for money, to fulfil their own needs and passions such as those relating to sadism and sexuality, and to achieve life goals they themselves may not have been able to achieve.

Criminality and Imprisonment

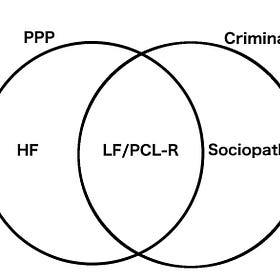

As stated several times already in this series, while all PPPs break “laws, rules, regulations, and agreements” (they are “not agreement capable,” as a certain foreign minister once said), not all of them engage in overt criminality or go to prison. High-functioning PPPs outsmart the justice system using both legal and illegal tactics and successfully project the image of a model citizen. They develop “powerful connections and networks” that help them in this regard. Participants ascribed this ability to variable features like intelligence, social class, education, good parenting, good executive functions and impulse control.

Tactically, they use subtler control methods, e.g. using psychological methods over physical, such as manipulation and persuasion. They are more cunning than the lower-functioning types. Mitchell makes sure to point out that just because they are more likely to use less overtly aggressive tactics, that does not imply they are any less dangerous.

Professions and Employment

While Mitchell’s sample size for explicitly mentioned professions was too small to be representative, those listed give some hint as to the variety of positions PPPs may hold. In order from most to least mentioned: entrepreneur, corporate leader, medical professional, law enforcement, legal professional, religious leader. Those less frequently mentioned ran the gamut, from car mechanic and gang member to accountant and musician.

As she observes, these challenge the idea that DPs “are drawn to roles that have risk and alleviate boredom.” Rather, some suggest another possible motivation: “the need for control and power and sadism.”

Knowledge Gaps

Ninety-five percent of participants believed that we have collective gaps in our knowledge of PPPs. These include: prevention and management, origins, motivations, and how to understand the PPP’s success in fooling people, which can appear at times to be almost supernatural. I recall bringing this up in my interview with Dr. Mitchell, how onlookers will think it ridiculous and inconceivable that someone (particularly the PPP) could do such a thing, and yet believe the PPP when he blames the innocent party of doing the exact same thing.

Certain “structures” came up repeatedly, which participants believed hindered our knowledge, including: reliance on psychometric assessment tools, siloed research approaches, lack of shared definitions, and the difficulty in studying high-functioning PPPs. These gaps result in certain authoritative groups, such as personality researchers, lacking a sufficient understanding of the problem.

The Problem

As big a problem as PPPs pose, there is a greater one: ignorance. Even if gaps in our knowledge still remain, most of the population lacks even the basics, and as one respondent put it, “Gaps in the knowledge of ordinary people means that abuse goes unpunished, victims are not believed and are retraumatised when they try to get help.” As Lobaczewski would put it, such gaps act as ponerogenic openings for the actions of socially and politically active psychopaths.

Closing the gaps in our knowledge is essential to dealing with the problem. That knowledge, in and of itself, acts as a protective measure. Lobaczewski makes this point repeatedly, and Mitchell echoes it in this section of her thesis. Several participants identified the problem, writing, “there is not … a consistent message,” and, “Lay people, which are most of our community, do not have knowledge let alone a willingness to believe what is unbelievable.” “If we don’t have a clear and strong popular conception, then it is very difficult to counter the destructive role that they play in society.”

An incomplete definition which focuses primarily on criminality may cause people operating on that definition to “underestimate, and overlook, the potential harm caused by someone with a DP within everyday interpersonal relationships,” or within “respectable” or “responsible” positions in society.

A clear understanding of the PPP, by contrast, makes it “easier to expose and hold people of DP to account.” For instance, with the proper knowledge, “there might be safeguards in place organisationally to prevent such people holding positions of authority.” This is precisely what Lobaczewski recommended as necessary to prevent the potential development of pathocracy.

However, several of the study’s respondents felt that even with an agreed-upon definition, “these types will still impact other.” After all, we have a definition of pedophilia. Another responded:

Society is only protected if behaviours rise to the level of a violation of law resulting in incarceration or if the behaviours do not violate the law but can be shown to be harmful to the individual or others, resulting in institutionalisation.

On this, Lobaczewski wasn’t entirely clear. He seemed to believe that institutionalization would only be necessary in certain cases and that observation and control of psychopaths in the general population would be sufficient in many cases, perhaps akin to something like a cross between a sex offender registry and parole or community supervision.

A popularization of accurate information about PPPs would help mitigate another problem. For many without such knowledge, the exposure of a PPP can have some strange effects.

Where someone of DP is exposed for their nefarious deeds and malevolent nature, … people are often so disturbed by being presented with information about a person of DP, they know that they often become angry at the messenger and/or the target/victim. … people generally push back, try to justify, make excuses for the person of DP, question the espoused experiences of the target/victim, and challenge the person who exposes the person of DP.

Mitchell quotes the work of Dale and Alpert:

The stories are so complicated and painful that our unconscious mind employs defences such as dissociation from the victim’s plight. There also is a tendency to identify with the perpetrator. It is easier to deal with the predicament of the perpetrator than relate to the intense pain that the victims endured and continue to endure.

Such people do not believe such allegations because the distance between what they think is possible and what they are presented with is too great. This results in cognitive dissonance and the attempt to create a suitable rationalization to retain one’s previous yet faulty worldview. Lobaczewski calls this conversive thinking.

In an earlier article in this series I noted how Mitchell and Lobaczewski both highlight the dangers of a poor definition of psychopathy. It allows psychopaths to operate in the dark, outside the reach of public scrutiny.

The Varieties of Predatory Experience

We’ve now covered the attributes and tactics from Karen Mitchell’s persistent predatory personality (PPP) model. This post rounds out the model with a number of differentiators. In other words, these items are not diagnostic, because they will manifest differently in dark personalities (DPs) on an individual basis.

Lobaczewski claimed that such a definition was deliberately employed in communist psychiatry in order to mask the psychopathic nucleus of pathocracy and forestall its diagnosis. In this chapter Mitchell makes a similar point, quoting six study participants who believed that “key academics and researchers in the field of DP are themselves of DP” and that these researchers “actively engage in tactics to block the kind of research undertaken in this study, preventing accurate research from being published.”

I used to think it was just the catch-all diagnosis of “antisocial personality disorder” that was the problem, and that psychopathy was relatively free from ambiguity, but after reading Mitchell’s thesis, I’ve changed my mind. Even the commonly accepted definitions of psychopathy are part of the problem.

9 times out of 10, when I have talked to people about my father's neglectful treatment of me, their first reaction is to make excuses for him and indicate, subtly, that I am exaggerating or am partly responsible for my treatment, "It can be a thankless task raising a boy", "I'm sure he did his best", "All families are a bit dysfunctional" etc etc. If they say these things to me, an adult man, you can imagine the kinds of denial and victim blaming that children get when they complain about how they are treated at home. It's alienating at best, literally maddening at worst being told by any adult one might dare to open up to that you are exaggerating or being unfair to a parent when that parent is a furtive monster.

"Such people do not believe such allegations because the distance between what they think is possible and what they are presented with is too great. This results in cognitive dissonance and the attempt to create a suitable rationalization to retain one’s previous yet faulty worldview."

There is an aspect of projection to this. The disbelief presented in the face of verifiable evidence, is routinely expressed as "What reason could they have for doing x, they have nothing to gain from it?" That response originates from projecting a personal motivational framework onto the range of options the DT type operates under.