This world, it deserves a better class of heroes. Instead, we get Marvel.

That’s not to say there are no genuine heroes in our stories. You can still read an old book if you want, or watch some Turkish historical fiction. But slogging through the modern Hollywood superhero film franchises as they flail about is like auditing a lesson in psychological mediocrity.

Last month, The Saxon Cross made some interesting observations on the modern hero in his piece “Marvel Morality”:

On the subject of mercy, for example, our contemporary heroes are fairly hopelessly muddled. Many heroes are decidedly unmerciful—Odysseus being the OG Doom slayer. Mercy can be done right, but in its modern incarnation it tend to go something like this: mindlessly kill a bunch of people (either bystanders or low-rung baddies “just doing their jobs”—it’s the collateral damage way), but when it comes to finally facing off with the big bad, go out of your way to hold back, get self-conflicted, and give him one last chance to redeem himself.

How about sparing the innocent and the low-level criminals and killing the weapon-of-mass-destruction personified instead?

A great villain is hard to kill, admittedly, because repeat future appearances are both entertaining and highly profitable. But a character’s moral code should at least be consistent. The Saxon Cross concludes this point:

Mercy is not a bad thing. But it is almost always used inappropriately in modern media like this. It is used not as true mercy, but as nauseating moralizing.

As a result of this inability to define true evil and treat it as such, our heroes must also become less heroic. Our popular media is filled to the brim with antiheroes.

On that second point, screenwriters would benefit from reading some actual true crime, and even one book on psychopathy (hint hint)—instead of the lazy psychoanalytic projection of juvenile inner conflicts onto super-villains that we routinely get instead.

But I want to make a different point here.

One of DC’s latest offerings, Black Adam starring Dwayne Johnson, broke the mold a bit in the mercy department. The character Black Adam isn’t just unmerciful, he’s more of a Shazam first and forget to ask questions later kind of guy. Getting in his way means getting dead. Needless to say, this makes for at least an interesting counter to “Marvel morality.” And where Marvel morality does make an appearance, it is set up a secondary conflict, parallel to the primary big bad CGI guy.

Black Adam wasn’t a great superhero film. I’m not sure I would even call it good. But at least it wasn’t Marvel. And it made clear to me one of the things I loathe about modern “heroes.” Let’s call it the Hero Incorporated model—the hero as day job.

In the film, Black Adam gets released from thousands of years of imprisonment and immediately goes on a rampage killing bad guys. As a result, the hall monitor cops of the DC superheroverse—the “Justice Society,” consisting of DC Dr. Strange (“Doctor Fate”), DC Falcon (“Hawkman”), DC Ant-Man (“Atom Smasher”), and DC Storm (“Cyclone”)—get sent in to neutralize the dangerous threat he poses to the military industrial complex.

Aside from Pierce Brosnan as Doctor Fate, who cannot help but be charismatic on screen, each of these characters is insufferably annoying. Mostly because they’re annoying people who just happen to be superheroes. Like Saxon Cross writes, “modern media does not just use this [demigod] archetype, but has totally replaced the noble hero with the everyman.” These heroes have super powers, but they’re otherwise average people who just happen to work for a hero corporation.

Atom Smasher inherited his suit from his uncle with all the majesty of taking over the family convenience store. Hawkman is a do-gooder who would take out JFK if his superiors ordered him to—he’s a letter-of-the-law type guy. And Cyclone—well, I don’t remember her well enough to comment. These guys destroy neighborhoods and cultural relics aplenty in their mission to take down Black Adam, and the film plays up how unwelcome they are to the locals, who see them as foreign meddlers protecting the evil corporation running their country—which is true, if a tad on the nose.

At one point, Black Adam is taken to a superhero-max prison, and the woman running it is even more smug, arrogant, and insufferable than the heroes who put him there. These people are supposed to be the good guys, and they just come across as soulless corporate ladder-climbers with all the virtue of middle management. In superhero land, everything is a soulless corporation.

And that’s what gets me the most. These people aren’t just boring; they’re actively annoying. They are not cool; they’re self-important posers. They’re not heroes; they just work here. And somehow that’s supposed to make them awesome. But it doesn’t, because it can’t.

I don’t know whether or not Black Adam was trying to make a point about the utter shallowness of the personalities that populate superhero movies. But it succeeded in demonstrating them, at the very least.

I suspect this is because most Hollywood writers are this shallow. They don’t understand heroism because the don’t understand virtue, or have any idea of what a developed personality might look like (tonic masculinity). They are annoying people, and so they can’t help but write annoying people. Perhaps. Either way, they will never be able to capture even an ounce of the qualities that make an Odysseus:

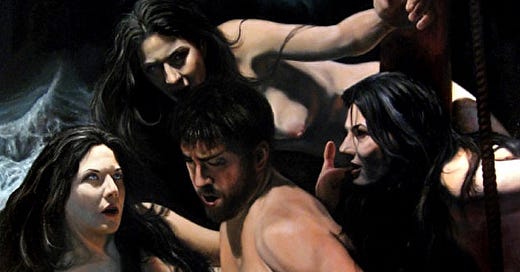

There she found Odysseus amid the bodies of the slain, all befouled with blood and filth, like a lion that comes from feeding on an ox of the farmstead, and all his breast and his cheeks on either side are stained with blood, and he is terrible to look upon; even so was Odysseus befouled, his feet and his hands above. But she, when she beheld the corpses and the great welter of blood, made ready to utter loud cries of joy, seeing what a deed had been wrought. But Odysseus stayed and checked her in her eagerness, and spoke and addressed her with winged words: “In thine own heart rejoice, old dame, but refrain thyself and cry not out aloud: an unholy thing is it to boast over slain men. These men here has the fate of the gods destroyed and their own reckless deeds, for they honored no one of men upon the earth, were he evil or good, whosoever came among them; wherefore by their wanton folly they brought on themselves a shameful death. …” (Od. 22)

Hero stories are supposed to be magical—not just amusing, and they often fail at even that. Here I use R.G. Collingwood’s somewhat idiosyncratic definition:

Magic is a representation where the emotion evoked is an emotion valued on account of its function in practical life, evoked in order that it may discharge that function, and fed by the generative or focusing magical activity into the practical life that needs it. Magical activity is a kind of dynamo supplying the mechanism of practical life with the emotional current that drives it. Hence magic is a necessity for every sort and condition of man, and is actually found in every healthy society. A society which thinks, as our own thinks, that it has outlived the need of magic, is either mistaken in that opinion, or else it is a dying society, perishing for lack of interest in its own maintenance. (Principles of Art, pp. 68-69)

If we were talking about the moral regeneration of our world, I should urge the deliberate creation of a system of magic, using as its vehicles such things as the theatre and the profession of letters, as one indispensable kind of means to that end. (ibid., p. 278)

Magic requires a decent psychological worldview. When culture falls behind in that department, art and entertainment suffer. That mediocrity then interacts with the mediocrity of undeveloped human potential in a feedback loop, reinforcing that mediocrity. In this sense, superhero films become both a symptom and a further cause of a moral disease:

… moral diseases have this peculiarity, that they may be fatal to a society in which they are endemic without being fatal to any of its members. A society consists in the common way of life which its members practise; if they become so bored with this way of life that they begin to practise a different one, the old society is dead even if no one noticed its death.

… [The Roman empire] died of disease, not of violence, and the disease was a long-growing and deep-seated conviction that its own way of life was not worth preserving. (ibid., pp. 95-96)

Mainstream culture currently lacks two essential things: an adequate understanding of evil, and an adequate understanding of heroism. Without either, that moral disease threatens to be fatal not just to society, but also to its members. Luckily there’s ponerology for the former. And tonic masculinity for the latter.

I will add that as far as villains go, I really liked both Heath Ledger and Joaquin Phoenix's Jokers. Can't think of any CGI villains that even come close.

Great observation about the constant slaughtering of the (semi-)innocent and the "he must have had a bad childhood" sparing of the true villains. Never really thought about this.

I really can't stand super hero movies for quite some time now, even pre-woke. The shallowness is just insufferable. But what to expect from a culture that is now literally chasing balloons LOL. Collingwood was right: we will go under because we stopped believing our culture is worth saving. Sadly, we might even be right.