The following article is a guest submission dealing with a topic Lobaczewski mentions only a couple of times in his works: anankastia, or anankastic personality disorder. All Lobaczewski says is that this is one of the ponerogenic personality disorders and that they are “silent despots” who are difficult to get along with and who “become causes of neurosis in others.” Martin’s article is thus a welcome addition to the study of ponerology, filling a gap. As you’ll see, anankastia is an important piece of the puzzle.

Tyranny and the Anankastic Mind

Our friends at the World Health Organization have recently released the 11th edition of the International Classification of Diseases, which attempts to inventory all of mankind’s maladies—including mental disorders. One interesting development in the ICD-11 is the inclusion of anankastia as a maladaptive personality trait domain found in those with personality disorders. In fact, the ICD-10 classified anankastic personality disorder as an extreme form of this quality. But what does it mean to be anankastic?

I think the word is best defined in the Bantam Medical Dictionary:

describing a collection of longstanding personality traits, including stubbornness, meanness, an overmeticulous concern to be accurate in small details, a disposition to check things unnecessarily, severe feelings of insecurity about personal worth, and an excessive tendency to doubt evident facts.

The American mental health diagnostic manual, the DSM-IV, contains an analog to this condition: the so-called “obsessive-compulsive personality disorder.” This label is problematic because it conflates anankastia with OCD, or obsessive-compulsive disorder, when the two are completely distinct from one another. Also outdated is the “anal retentive” designation, a term coined by perverted cult leader Sigmund Freud. Thankfully, this vulgar phrase has mostly dropped from the public vernacular. More recently, anankastia may be observed in the type of person known as the “Karen,” an objectionable slur against white women.

Considering the alternatives, anankastia is probably the best label for this trait domain, awkward as this word may be. For this reason, the labels “anankastia” and “anankastic” will be used throughout this essay to describe an extreme personality type, a collection of tendencies, or as a socio-psychological trend. Consider that while some people are more anankastic than others, we can all exhibit this tendency, sometimes, to varying degrees, which means it can be exploited in all of us. Also note that this author is not a professional psychologist, and words like “fixation” or “repression” are meant to be taken in their colloquial (i.e. non-Freudian) meaning.

Anankastic traits in action

Below are a list of traits I associate with anankastia. Some of these are identified by the ICD-11, and some are based on my own observation. In describing these traits, I will compare anankastia with other malignant personality types to which the reader may be more familiar—like narcissism—or less familiar, like schizoidia. Keep in mind that these are discrete characterizations, and in reality, an individual can possess overlapping traits (e.g. schizoid and anankastic). Here’s a list of what I consider the essential facets of an anankastic personality:

Limited empathy

Conscientiousness

Fixation

Perfectionism

Repression

Self-sacrifice

Hoarding

Lack of self-awareness

Imposition of rules

Inability to learn by observation

Limited empathy

Diminished empathy is a trait shared by several pathological personality types, including paranoia, schizoidia, and narcissism. Anankastics also demonstrate limited empathy, but in a unique way. The anankastic is so focused on the way she thinks things should be, and so righteous in her own assumed correctness, that she tends to lack a humane sense of propriety and will spout her opinions in a way that seems exceptionally tone-deaf. For this reason, she can read as narcissistic.

Both she and the narcissist crave power and acclaim, and while both will maneuver to control a social situation, the anankastic is more able to consider other peoples’ position due to her inclination toward conscientiousness, and can therefore build a more accurate model of a group dynamic. By contrast, the narcissist’s lack of empathy places huge blind spots in his social awareness.

The severe anankastic is so set in her ways that she can’t consider other perspectives, but she does consider their disposition. She imagines a chain of consequences for her actions, and she worries what people are saying or doing when she’s not around. The severe narcissist, however, is completely solipsistic in his perspective. It doesn’t occur to him that anyone does anything once they exit the frame of his experience.

Note that empathy (that is, cognitive empathy) is not the same as sympathy (or affective empathy), which is feeling for other people; empathy is a kind of abstract thinking where one can construct a model of someone else’s position, and imagine what they might be thinking. Empathy can lead us to sympathize with others, but also recognize when we’re being conned or manipulated. The paranoiac reflexively distrusts everyone because his low empathy causes him to view everyone as a potential threat; but Polyanna is also limited in her empathy—trusting to a fault.

The schizoid is, in modern times, often perceived as being on the autism spectrum; however, autism is considered a neurodevelopmental disorder, and schizoidia a defect of personality. Nevertheless, you know it when you see it: robotic, shallow affect, inability to connect with others, extremely left-brained. Thus, the label “autistic” is used here, interchangeably with “schizoid,” in favor of familiarity over precision.

Anankastics should not be confused with narcissists, nor with autistics—despite the surface similarity. Autistics can be hyper-analytical, miss obvious social cues, and come across as impolite or uptight. Those on the autism spectrum struggle to empathize with others. However, the schizoid can often reason with an open mind, because his low emotionality places less pressure on his thinking process—whereas the anankastic has high emotional pressure on hers. Her decisions are fear-based, her thought process closed and self-censoring.

Despite his free thinking, the schizoid demonstrates interpersonal naïveté due to his inability to read others emotionally. The narcissist is highly credulous for the same reason, and casually dishonest at the same time. The anankastic, however, is highly conscientious, and therefore extremely honest. She has an internalized sense of integrity—an admirable trait. She settles all her debts and returns every favor, as a matter of honor. It’s hard for the anankastic to tell a lie—even a white lie—and a “victimless crime” is no excuse. Even if no one knows what she did, and no one was directly affected, she still knows she did something wrong (or, for the religious anankastic, God knows what she did) and she has to live with herself.

Conscientiousness

This is because the anankastic personality is, paradoxically, highly conscientious in spite of her limited empathy. She makes fear-based decisions (“what if something goes wrong?”) and worries that her decisions may carry repercussions for others. “What if I take too long and it causes him to be late?” she worries, anxious that she’ll inadvertently place someone at a disadvantage. But this is all based on an abstract idea of what she thinks could affect someone, and not on the actual feedback she receives from others—spoken or otherwise.

The anankastic may send the most elegant and formal invitation to her party, and a touching thank-you note to all attendees after the fact— and yet present as cold and preoccupied at the actual event. Burdened by responsibility, threatened by perceived impropriety and racked with guilt, she’s never really living “in the moment”, but rather in anticipation of an expected outcome, in fear of unintended consequences, or in rumination over disappointing results.

Fixation and perfectionism

This is where anankastia becomes confused with obsessive-compulsion, or OCD. Both types of people become absolutely fixated on small, often inconsequential details. Both types are procedural to the point that the process itself becomes a ritual more important than its own objectives. The most crucial difference between the two is that people with OCD understand they have a problem. They don’t actually want to obsess in this way, but feel compelled to do so.

Anankastics, on the other hand, want to dwell on small details, and believe their way of doing things is the only, truly correct way. Obsessive-compulsion is considered a component of anxiety, while anankastia is a defect of character. The obsessive- compulsive individual can seek and obtain help for his condition, because he wants to alleviate the burden of his anxiety. The anankastic, by contrast, believes in her pursuit of ideal perfection, and her hyper-perfectionism makes her unlikely to even identify fault in her patterns of thinking and behavior—much less admit fault. It is thus extremely unlikely that someone so pathologically inflexible would willingly undergo the personal transformation necessary to shed her anankastic traits, even if she wanted to—which she doesn’t.

The process of completing tasks is doubly complicated for the anankastic: first, because of her perfectionism; and second, because of her non-heuristic approach to problem-solving. She considers trial-and-error, rules of thumb and educated guesses as improper or amateurish, relying instead on her formal instruction. We all have to “fake it till we make it,” sometimes, and “winging it” gives us real-world, on-the-fly training that you can’t get in a classroom. But because the anankastic refuses to operate in this way, she limits her own opportunity for growth.

Repression

“‘I have done that,’ says my memory. ‘I cannot have done that,’ says my pride, and remains inexorable. Eventually—memory yields.” —Friedrich Nietzsche

Anankastics are controlling and driven by emotion, but they aren’t selfish. The narcissist may want to be seen as good by others, and the anankastic wants this, too, but the anankastic wants to actually be good and moral. Again, not a bad trait to have! She really does want to act with integrity and can be very hard on herself. But she is also human, as we all are. She can become jealous, spiteful, or mean-spirited, as can anyone—and even more so, because she is extremely petty and uncooperative to begin with. But she’s also highly scrupulous and wants to believe she is motivated by altruism, so she won’t admit to herself when she’s misbehaving.

The difference between the narcissist and the anankastic, in this case, is subtle, yet distinct: The narcissist is fundamentally selfish, and he uses motivated reasoning to rationalize whatever actions will benefit him personally; the anankastic is not generally selfish, but when her lesser nature asserts itself, she will choose to justify her motivations as altruistic.

The anankastic’s mind is a labyrinth of circuitous reasoning and self-deception. She fears not just the consequences of her actions, but the implications of her own unpleasant thoughts. For this reason, sinful notions are terminated before they are annunciated in her internal monologue.

Self-sacrifice

The anankastic is often high performing—and thus successful—but the life she leads is rarely one of luxury. For one, she’s usually incredibly miserly, hoarding her money for “a rainy day” and never spending it; hence, her surroundings are often spartan and she lives well below her means.

The anankastic often denies herself life’s pleasures, seeing them as frivolous and self-indulgent. Despite her penchant for compulsion, she’s unlikely to become an alcoholic or a drug addict, and she’s usually rail thin, if not outright anorexic. The anankastic believes that sacrifice is morally purifying—a virtue unto itself.

Hoarding

This one is actually not an essential trait, but it correlates strongly with anankastia. Anankastics have a tendency toward hoarding, as they’re afraid to discard something which may be of some use, someday. What’s less recognized is that anankastics also hoard information. The logic seems to be, “I have this piece of information that someone needs to do their job, and if I withhold it, I can use this as leverage.” Anankastics love to gatekeep information in this way. However, the point of gatekeeping is that when the other person gives you what you want, you then open the gate for them.

In my experience, an anankastic coworker will dangle information over your head to make you do something, and then when you do it, she still won’t release the information you need—or does so very reluctantly. The rationale seems to be that if she spends her bargaining chip, then she won’t possess it anymore. This is obviously self-defeating, because people will stop transacting with you if there’s no payoff.

I may be incorrect in my explanation of information hoarding, but I have observed that the anankastic is excessively private and coy. You could probably get her to take a secret to her grave if she believed it was her duty.

Lack of self-awareness

This is an important feature of the anankastic personality: it lacks introspection, which is why, like the narcissist, the anankastic can appear unintentionally absurd, and can be trolled into making herself ridiculous. Unlike the narcissist, she can be made to feel guilty and to seek redemption, so she can certainly internalize fault; even so, she can’t really take a step back, evaluate her assumptions, and analyze what it is that motivates her behavior. Despite her attention to detail, she lives an unexamined life, and, despite her righteous certitude, her beliefs rest on an insecure foundation. In fact, her impulse to impose her way on others is partly because it makes her feel more secure. She proves her correctness to herself by reinforcing the integrity of the rules, and she does this by imposing them on others.

Imposition of rules

The anankastic’s world is scaffolded by rules she assumes are universal, and she is constantly agitated by assumed impropriety, insufficient excellence, and perceived slights. “You should know better,” she assumes of those who violate her unspoken ordinances. She either buries her judgment under disingenuous courtesy, or delivers it in a fit of indignation—but whether seething or scolding, she can never accept that others simply possess different standards than her own.

Thus, the anankastic seeks rule-making powers so that she can enforce her standards. When a narcissist has the power to make the rules, he rigs them in his favor; but the anankastic’s vision of fairness does not necessarily benefit her disproportionately (or even at all), and when it does, it’s simply to the extent that she can monopolize power, because she can’t trust others to make things truly fair. She may use the rules to her own advantage, but to her, the rules themselves have a sacred quality and apply to everyone—even herself. If extemporaneous circumstances require her to bend or break the rules, she might use pretzel logic to justify her rule-breaking, in an attempt to resolve her own cognitive dissonance.

Anankastics fear hypocrisy and inconsistency, and must have an internally consistent moral code. Conversely, narcissists (and psychopaths) believe rules are for other people, so hypocrisy and double-standards don’t bother them at all.

Inability to learn by observation

This is a very important factor in defining anankastia, and one that I think is often overlooked. Anankastics do not see what is right in front of them, because they can’t see past what they think should be there. In this way, anankastia becomes more than a feature of personality, producing significant perceptual cognitive distortions.

You may have taken this test before, at some point in your life: an instructor holds up a flash card, and on it is written a common phrase, like:

A BIRD IN THE HAND IS WORTH TWO IN THE THE BUSH

The instructor will show you the card for a couple seconds, put it down. then ask what was written on the card. Most people will say “A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush” because they don’t notice the word “THE” printed twice. A variation on this test is to srcabmle the lteters of some words, but keep the first and last letters intact. Your brain will recognize what words are supposed to be there, and in many cases won’t even recognize the typo. This is because our brains constantly fill in or “correct” incomplete information. This kind of cognitive revision is something we all do, to varying degrees.

The power of suggestion is more effective on some people than on others, and the highly suggestible are those more likely to trust the guidance of others than to rely on their own judgment—or even their own senses. Con-men and hypnotists call this a “mark.” While the anankastic isn’t whimsically suggestible in this way, and is actually very stubborn and headstrong, once she latches on to an idea it puts her under a kind of hypnotic spell that no amount of contradictory evidence can break.

The anankastic relies on her own assumptions and prejudices to understand the world, and not her observations. I had a teacher once who told me there isn’t a single word in the English language that starts with the soft “zh” sound, as in mirage or massage. “What about the word genre,” I asked her (her rule was probably correct but didn’t consider loan words). “Genre?” she replied, pronouncing it correctly. She pronounced it again, under her breath, and then informed me, with total confidence, that the word is pronounced “John-ra” with a hard J. The obvious incorrectness of this assertion, and the fact that she had just pronounced it zhanra a moment earlier, and indeed, presumably, her entire life to this point, was not enough for her to reconsider her rule.

Pathology and pathocracy

Political science is the discipline through which we typically define systems of government, but poli-sci is limited in its application to corrupt or tyrannical systems. The reason is that a corrupt system is less a function of design than of its own subversion or degradation. “Conspiracy theorist” can’t really be considered a political persuasion, because a conspiracy theorist is less focused on how the government should function, and more on the ways in which it undermines its own existing, ostensible purpose.

Furthermore, political science fails to explain mass social phenomena, which may not be “political” in the strictest sense but which shape and impact society. Luckily, several authors have attempted to explain societal dysfunction by combining their political observations with an analysis of mass psychology. Notable works include The Origins of Totalitarianism by Hannah Arendt, Political Ponerology by Andrew Lobaczewski, and The Psychology of Totalitarianism by Mattias Desmet. All three books explore the mass psychology of tyranny, with Ponerology attempting to explain the way psychopaths can take over a society and warp it in their own image.

Psychopathy is a topic for another time, and is better explained in the aforementioned work. Popular visions of dystopia conjure the image of a psychopathic despot oppressing the terrorized masses, or a closed bureaucracy of Machiavellian overlords unaccountable to a bewildered public. While there may be validity to these conceptions, they portray a simplistic dichotomy between the ruling elite and the mass population, which fails to illustrate the structure of evil.

In reality, a system that rewards ruthlessness and deceit is obviously going to favor psychopaths over normal people, and over time, this criminogenic environment will concentrate psychos at the top. Corporate and intelligence structures are two such examples, and it’s no surprise that both produce a high number of powerful, psychopathic individuals.

These people generally can’t rule directly, however, for a couple important reasons: first, their power depends on compartmentalization, in which their words and actions are tailored to target the individuals they need to manipulate. This kind of maneuvering is more difficult to do in the pubic eye. Second, the psychopath wears a mask of sanity that isn’t likely to convince the entirety of the pubic, which is why he surrounds himself with other, subservient pathological personalities.

The most important of these personalities is the aforementioned narcissist, who craves power but also attention, and who basks in the public spotlight. He has no morals or convictions, so he’s easily molded to play whatever part is necessary. He’s so self-interested and so lacking empathy that he’s oblivious to the machinations of psychopaths in his midst. And unlike the psychopath, who is unburdened by human emotions, the narcissist is entirely ruled by his own childish ego—making him a willing manipulator who is easily manipulated himself. He’s also easy to blackmail, due to his fear of public humiliation and his propensity for misbehavior. Thus, the narcissist becomes the ideal puppet for the psychopathic puppet master, especially if the puppet possesses some psychopathic traits himself—as narcissists often do.

A society under psychopathic control produces a spirit of narcissism, both among its celebrities and politicians, and in a general culture that permeates throughout the public. Ordinary people model their behavior after the vapid, superficial quality of the figures held up as society’s leaders. A population of selfish, self-obsessed individuals is unlikely to question the nature of society, or to work together to challenge the power structure.

But if psychopaths represent the hidden hand of power, and narcissists are their figureheads, anankastics are the important next step between the elite and the masses of ordinary people. Anankastics are not true leaders, nor are they followers, but rather the regime’s enforcers—its bureaucrats, pundits, policy wonks, middle managers, stool pigeons, hall monitors, and other petty tyrants.

Anankastia in politics

A corrupt, tyrannical regime needs people to do its will and not ask questions. Narcissists make good figureheads in this kind of order, because they’re often high- functioning, but incurious and imperceptive. High-functioning autistics/schizoids are narrowly-focused, unintuitive, and potentially useful, but they may present a liability if they can think freely without being cowed by emotional and societal pressure. Anankastics are often highly productive and effective, are imperceptive, are easily controlled by establishment pressure, and are obedient to authority—making them the perfect Janissaries.

Anankastics are not sheep, and they’re not blind adherents. Remember that they are enforcers, not followers. They don’t rely on the social proof of ordinary people to make decisions, and they aren’t afraid to go against their peers. They think they’re smarter than those around them, and more qualified to make decisions. Therefore, propaganda tailored to the anankastic cannot simply project that “everyone’s doing it.” You need official (looking) reports and authoritative (seeming) organizations to bring the anankastic population to heel.

Anankastics must maintain a coherent mindset in which all conflicts and discrepancies are resolved, in a holistic, totalizing worldview. This becomes a problem in the postmodern order, which is the result of intellectual deconstruction. Postmodernism’s rejection of epistemic certainty and objectivity leaves little terra firma to support the anankastic mind, yet this is the culture in which we live, and so we see interesting results when postmodernism and anankastia collide.

Uncompromising tolerance

“My dear brethren, never forget, when you hear the progress of wisdom vaunted, that the cleverest ruse of the Devil is to persuade you he does not exist!” —Charles Baudelaire

The anankastic is binary in her thinking: there’s a right way and a wrong way; there’s this and there’s that, and if it isn’t this, then naturally it must be that. Her mindset trends toward a polarized, Manichean conception of good and evil. However, the contemporary, Humanist perspective insists that deep down, we’re all the same, and it characterizes people not as “good” or “bad” but as “good” and “misunderstood.” Everyone is basically good, and bad behavior is the outcome of either suffering or misfortune brought upon the offender.

When an anankastic learns and embraces this ethic, and then encounters antisocial behavior, she can’t believe or accept malice: “What kind of a person would do such a thing?” The logic seems to be, “I’m a good person, and we’re all basically alike, which means other people are basically like me. I would never think to be so treacherous, so they must have misspoken, or there must be a misunderstanding.” And when that interpretation falls apart, and there’s no way to explain away the behavior: “I would never think to be so duplicitous, unless I was in a really dire situation, or unless I was hurting inside.” So then the cope is that the person must be lashing out in some way, or reacting to some larger injustice. In other words, the anankastic can sort-of put herself in someone else’s shoes, as long as the person in those shoes is still thinking with her brain.

When she does this, it’s because she needs her real-life experience to conform to her existing assumptions about human nature—in this case, “everyone is basically good.” It is doubtful that the belief in universal goodness is a feature of the anankastic personality, though, but rather a function of upbringing and education. An anankastic raised on secular humanist ideals might think this way, but an anankastic religious fundamentalist, raised to believe that men are wicked sinners, might only assume good faith among her co-religionists.

Contemporary liberalism embraces Karl Popper’s view that everyone should be tolerated—except the intolerant. This natural contradiction is especially so for the anankastic, who is intolerant by nature. She seems able to simultaneously believe that everyone is basically good, but that there are also bigots in society that are irredeemably evil. In this worldview, “bad” and “intolerant” are practically synonymous. To the anankastic, a person who transgresses the assumed moral code is bad, but then it’s intolerant to think of people as bad—unless he’s intolerant in some way, in which case he’s unambiguously bad. This means that when someone deviates from her belief system, she is motivated to perceive him as intolerant in some way, so that she can give herself license to hate him.

Unconditional tolerance and self-sacrifice might explain the white liberal who is fervently, stridently anti-white. This obviously doesn’t benefit her, her family, or her racial kin. She believes this position is especially altruistic because it’s self-defeating. Of course, it also pisses off self-respecting white people, and non-whites don’t respect it, either. The anti-white anankastic lacks self-awareness, and is unobservant, so she doesn’t recognize how much this erodes her status with everyone except other anti-whites—but of course, the more anti-white rhetoric she espouses, the less likely she is to ever reverse course, until she ends up in the exclusive company of other anti-white white people.

It is often observed that the loudest of such people have few non-white connections, if any, and all their friends are white. I believe this is because the anankastic white liberal has rigid, unexamined assumptions about how one should and shouldn’t behave, and because her background and upbringing inform these assumptions, people of very similar walks of life are least likely to offend her sensibilities.

Moral crusades

Anankastics can be motivated to fanaticism, to hate and want to punish non- conformists, and to support evil with a clean conscience if they believe they’re following the rules. Their code of ethics is more legalistic than humane, and once acting on her righteous determination, the anankastic crusader is unlikely to second- guess herself when the deleterious effects of her actions become apparent.

The anankastic’s state of mind is one of perpetual, repressed frustration, but she is afraid to get angry on her own behalf. Moral outrage at injustice is altruistic and selfless, however, and so a moral crusade offers an opportunity to expend this pent- up, negative energy. Consider this quote by Aldous Huxley:

The surest way to work up a crusade in favor of some good cause is to promise people they will have a chance at maltreating someone. To be able to destroy with good conscience, to be able to behave badly and call your bad behavior ‘righteous indignation’ — this is the height of psychological luxury, the most delicious of moral treats.

Rule by experts

Anankastics practice credentialism. If you don’t have a certificate and a title, you’re not an expert. Rare is the truly autodidactic individual, and never is the anankastic such a person. Her mind cannot educate itself. This is largely why she scoffs at the notion of self-education: because she could never learn through curiosity, dialectic, experimentation, and experience. She learns by instruction, and the extent of her self-education is to read the manual.

The anankastic needs to believe in a functioning meritocracy, so she will trust an official leader as long as he projects a sense of authority—even if it’s completely fraudulent. A leader who projects crassness or mediocrity upsets the anankastic because it becomes so difficult to suspend her disbelief when faced with such an obviously unathoritative figure.

The anankastic is not very observant, and she doesn’t totally rely on social proof to make decisions, but she does take certain cues from a public figure to determine if he’s any good. One is whether he’s articulate. This is very important. Another cue is whether he’s well-mannered. He can’t be seen to transgress social norms, and the anankastic, who is herself highly scrupulous, holds others to very high standards of behavior. An authoritarian leader must project an air of altruism, of stoicism and virtue, and, above all, of competence—even if his actions obviously betray this posture. Conversely, the populist demagogue who insults his opponents with vulgarities and speaks at a 5th-grade level is likely to provoke the anankastic segment of society into an apoplectic fury.

Anankastic revolutionaries

The anankastic needs to believe that the system is fair, and not just fair but perfect; that the construction of rules and procedures contains within it an almost mystical clairvoyance, in which all questions can be answered and all problems solved; and that when this system is operational, any real life dysfunction can be “debugged” by perfecting it with more rules and procedures.

When real-life results reveal the presuppositions of a planned system to be infeasible, the anankastic will either refuse to acknowledge this reality, or assume that the agenda wasn’t pursued closely or aggressively enough, and then double- and quadruple-down on her plan. When this makes everything even worse, she will either octuple-down or start blaming “wreckers” in the group for sabotaging the system. Or, she will defend the system at the expense of its victims. When the agenda leaves casualties in its wake, she assumes those people deserve what they got, because they didn’t play by the rules or failed to meet its standards.

However, again, this defies the postmodern, humanist hermeneutic which assumes behavioral outcomes are strictly determined by societal inputs. From here we can see the internal contradictions that society’s planners attempt to resolve, but again, anankastics are not actually society’s planners, but its enforcers. For them, an unstable system creates a great deal of cognitive dissonance and can lead to revolutionary fervor.

The agitprop so often targeted at the anankastic is as follows: “Here’s an extreme edge case where the legal system completely failed someone. This proves that the entire system is fundamentally, fatally flawed and needs to be completely scrapped and reinvented.” Never mind the horrible judgment exercised by the victim, or his just happening to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. In this case, the system failed, which means it’s imperfect, which means it’s invalid.

The tenacious, pedantic nature of the anankastic makes her seem schizo-autistic. Both believe themselves more rational than others, but the schizoid is ruled by logic while the anankastic is actually ruled by emotion. The smug, anankastic liberal assumes she has a monopoly on rational thought, primarily because she doesn’t hear any reasoned, illiberal arguments, and she doesn’t hear the arguments because an illiberal person is not worth engaging. In fact, to consider an illiberal line of reasoning makes her queasy, like an Irish Catholic who sins simply by having impure thoughts. Dialectical argumentation is not the process by which she forms her understanding, but rather by instruction, so there’s no entertaining an opposing viewpoint, even to craft a counter-argument, or even as a thought experiment—she can’t entertain an idea without embracing it, so considering a dissident position is like hugging a tar baby.

That said, she will listen to an argument further to the left than her, if it can be made in such a way that it confirms her biases, or plays on her insecurities if it’s implied she’s not dedicated enough to her own principles. This pathway can be exploited to radicalize her, like so: “you accept x, and therefore, it only follows that you would embrace y; and once we’ve established y, then naturally you must also embrace z.” Poverty and exploitation should be alleviated; therefore, gulags. Love is love; therefore, child genital mutilation. Once she accepts a premise, she is now receptive to the next premise. And because she can’t entertain an idea without embracing it, the new premise is absorbed and she’s primed for the next one.

Again, though, this process of radicalization requires intolerance of any dissenting opinions, and intolerance is anathema to the liberal, humanist worldview. So how does the anankastic resolve this? She resolves it by pathologizing her opponent. She claims she wants to understand him, but in reality she attempts to “understand” what’s gone wrong with the mind of someone who hasn’t naturally arrived at the same, extreme conclusions as herself. Hence the unctuous, condescending way she pretends to seek understanding with dissenting, illiberal voices.

The extent to which the anakastic “does her own research” is to look up what the official experts say. She mistakes her pedantry for rational skepticism, and believes herself more enlightened than others.

Scientism

This leads to scientism as a method of control. Science is presumed to be perfect and gives us the answers we need. Science tells us x, and therefore if you don’t believe x then you don’t believe in science, and your opinion is invalid. If you can pack every ideological premise into this framework, then it’s assumed that no ideological premises can be challenged.

There are a number of reasons not to “trust the science”:

The missing aspect fallacy;

Corruption of the scientific method—e.g., paying a team of scientists to “peer review” your product, then claiming their methodology is a trade secret;

The fallibility of human scientists;

Complicated computer models as a substitute for actual scientific experimentation;

The scientific method’s ability to disprove, but not prove;

Science that treats subjective matters as empirically quantifiable; and

Outright scientific fraud.

The scientific community has suffered a replication crisis since at least 2005. When scientists attempted to reproduce the results of an accepted, peer-reviewed and published scientific finding, they were unable to do so about 40% of the time. However, the failures to replicate findings vary significantly across disciplines, with the worst results in biomedical research, economics, and the social sciences. This implies that the scientific establishment has more of replicability “problem” in the hard sciences than a crisis, but that these other disciplines are either corrupted by special interests or are soft to the point of being semi-scientific.

This isn’t to suggest that social science is without merit, or that economics isn’t an important or valuable discipline. However, it’s clear that Scientism, or science as ideology, can exploit the less-empirical disciplines for the purpose of mass manipulation and revolutionary fervor.

An early example of this is the Jacobins, who forcibly replaced the Catholic church with the Cult of Reason. This included, among many reforms, the imposition of the Revolutionary Calendar, which reset the year to 1 and which made every day 10 hours long, 100 minutes per hour and 100 seconds per minute. Those who rejected the Jacobins’ reforms were subject to mass execution.

An even better example would be the Bolsheviks, whose “Short Course” textbook codified Marxism-Leninism into the “science” of dialectical materialism. The claim of Bolshevism’s scientific basis allowed the party to label their opposition as against science itself. The Soviets eventually pathologized disagreement to such a degree that they declared political dissidents to be psychologically unwell and had them committed to psychoprisons.

None of this is to imply that anankastia is exclusive to leftism, or to liberalism. There are plenty of religious fundamentalists who exhibit highly anankastic behavior, as well as extremely doctrinaire, anankastic (and schizoidal) libertarians who will try to enforce the non-aggression principle, and claim Ayn Rand’s objectivism applies to all these aspects of reality that are actually quite subjective (Rand herself was guilty of this). Scientific inquiry and ideological struggle are both important, even noble pursuits. However, there is a subtle but important distinction between one’s quest for logos and veritas, versus an emotional need to be righteous and correct.

Speech regulation

In a pathocracy, psychopaths control and distort the language as a way of manipulating the public psychologically. Anankastics embrace, enforce and inflict this language on others—but they, too, are entranced by it.

Anankastics—along with psychopaths, schizoid/autistic types and narcissists—are put off and alienated by dry sarcasm, situational irony, and double entendre. In order to appreciate irony, one must understand that looks can be deceiving, and that something’s actual, effective meaning can betray its official, ostensible meaning. This alienates the narcissist, for whom appearances and meaning are practically the same thing, and who doesn’t consider the intrinsic value of anything. It also alienates the anankastic, for whom meaning is static and inflexible. For this reason, you can usually filter out a lot of pathological people by observing who can understand and appreciate irony, and who cannot.

Sarcasm depends on tone, delivery, and context. Narcissists lack empathy, so they can’t read microexpressions or subtle inflections in tone. Anankistics can, but they struggle with the notion that context changes meaning. This is why anankastics like to police speech, and find political correctness reassuring: it’s a speech code with concrete do’s and don’ts, words you can and can’t use, and that these don’t change with situational context. For the same reason, they like explicit consent codes around courtship, even though these don’t work at all in practice.

Conspiracy theories

Anankastics are especially put off by novel takes, esoterica, or anything that sounds like a conspiracy theory, because this line of thinking implies that that you can tease out a deeper meaning by reading between the lines—which anankastics can’t do, and don’t want to do. An anankastic may be surrounded by scandal and intrigue, to which she is utterly oblivious. So intense is her aversion to conspiracy thinking that she leaves herself vulnerable to those who might use her as an unwitting pawn in a grand scheme.

Mark Twain once said that it’s easier to fool a man than to convince him that he’s been fooled, and this is especially true of the anankastic. She’s easily manipulated by social predators because of her stubborn, presumptuous, and unobservant nature.

Conclusion

Just as narcissism can describe a disorder, a personality trait, or a societal undercurrent, so too can anankastia describe these three phenomena. I believe our society is currently suffering the effects of extreme anankastia, both imposed by the pathological functionaries of the system, and as a general spirit possessing the public at large. While some social critics describe this as mass psychosis, I think it’s more accurate to see this as wide-scale anankastic neurosis.

We can see anankastia, retrospectively, in the kinds of people described by the novelists who warned us of the descent into social chaos. We see it in both the binary thinking and the “beetle like men” that Orwell described in Nineteen Eighty-Four, with their “scuttling movements” and “inscrutable faces,” “the type that seemed to flourish under the dominion of the party.” We see it in the “illiterate air” of Eric Hoffer’s True Believer, who “seems to use words as if he were ignorant of their true meaning.” We see it in the “oversocialized types” Ted Kaczynski describes in his infamous manifesto, the “rebels” who form the vanguard of state ideology. And we see it in the Kafkaesque quality of our current era, so named for the bureaucratic madness so vividly described by Kafka.

Society is hierarchical by nature. Some people have natural leadership qualities, and some do not. There’s no point in having natural leaders without a great number of natural born followers. While the progressive and the libertarian may believe everyone has the capacity for rational thought and a destiny for self-actualization, the last few years prove that this is obviously not the case. So, if large numbers of people are destined go along with whatever, then our best hope may be some emergent, more benevolent leadership.

Perhaps there is a role in a healthy society for an enforcer, someone who is steadfast in her loyalty, morally confident, carefully adherent and rigidly conformist. Technological progress once required the hands and minds of many people willing to, say, fashion arrows all day, with meticulous craftsmanship, in a design they didn’t invent and for a cause they never questioned. Perhaps the survival of the tribe depended on these people.

I feel some degree of sympathy for Karen, because the impulse to concern oneself with the affairs of others, and to reinforce the social contract, is not necessarily a bad one. Her mistake, if anything, is to think we still live in communities, and not the vestiges of community. It’s likely that a somewhat anankastic person is made more so by fear and anxiety, and I wonder if those who need order and structure to feel secure are becoming more anankastic as society’s structure continues to break down.

I hope this essay helps to explain a psychosocial phenomenon that was once difficult to define. It’s ironic that the heinous, odious World Health Organization, which has so terrorized the world population and which so threatens the fabric of society, has also offered us this framework to better understand the widespread pathology they have so exacerbated.

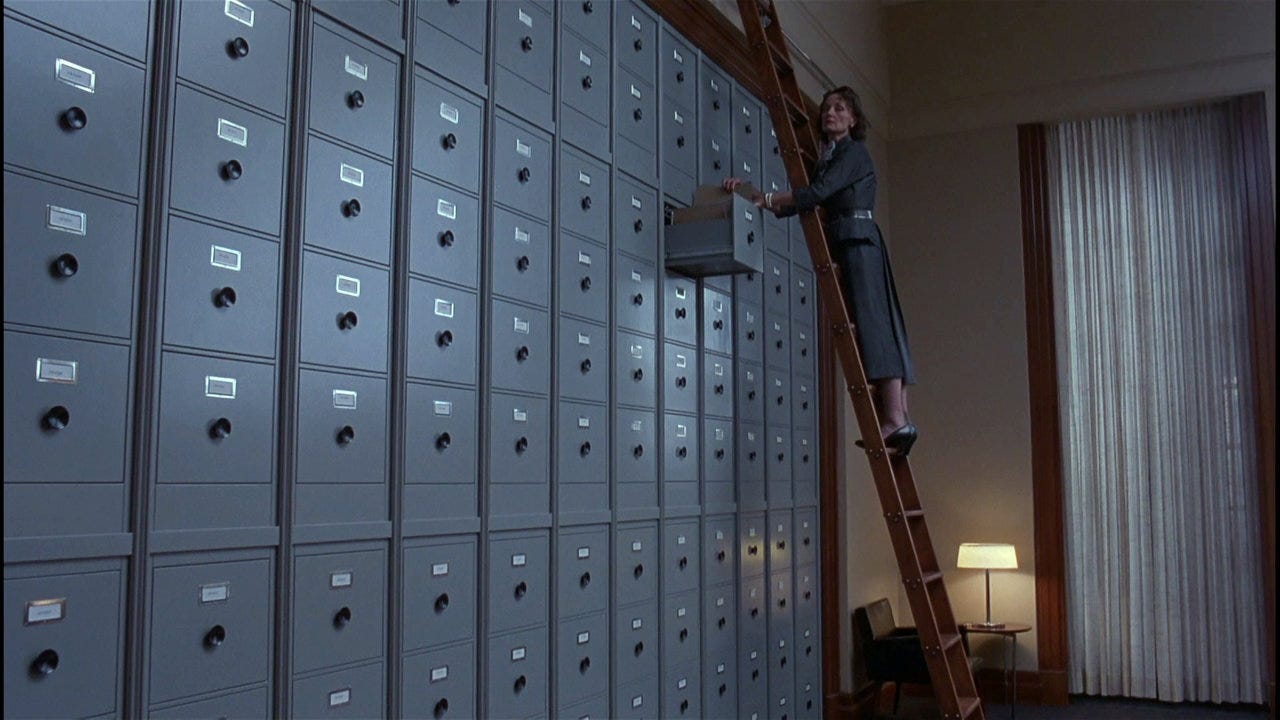

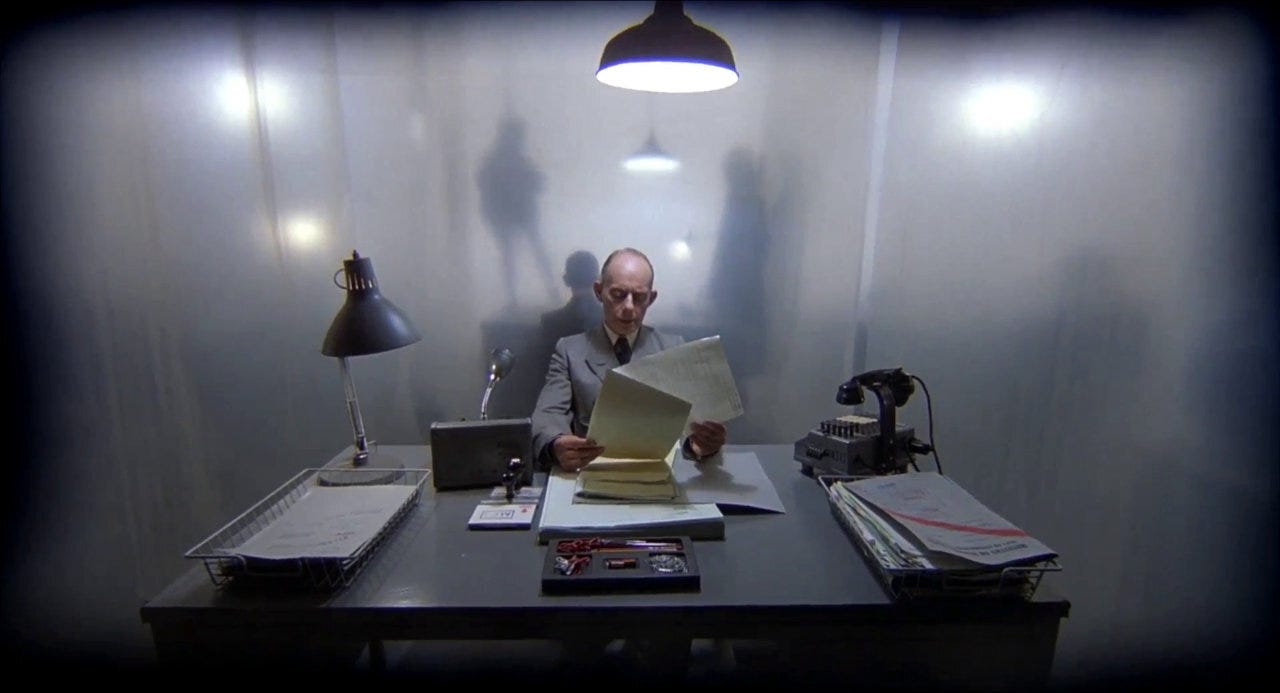

I was having a little difficulty getting my head around this Anankastia concept until you showed the shots from Terry Gilliam's "Brazil", then it all started to fall into place.

The first shot is just after the SWAT team bust into a nice family home to arrest the wrong guy, the officious Stasi-like bureaucrat informs him that he has "been invited to assist the ministry of information with certain inquiries". He then turns to the terrified wife and says, "That is your receipt for your husband, and this is my receipt for your receipt".

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nSQ5EsbT4cE

I think later in the movie, after the poor sap has been tortured to death, because he didn't know anything and The Ministry of Information had the wrong medical files, the wife actually gets a refund for her dead husband.

Once again science fiction shows us the way. If you want a vision of the future imagine a vast tribe of pettifogging administrators screwing things up - forever

I wonder if the sudden spike in anakastia isn't committed to our increasingly permissive and self-centered worldview. If you tell people, "You can be whatever you want and do whatever you want to do," most of them will run in terror to find somebody who will tell them who they should be and what they should do. In a society where truth is flexible and rules are whatever you want them to be, it's not surprising that many people will run toward Unquestionable Truths and Unbending Rules.