Left Is Right and Right Is Wrong

A ponerology glossary entry on paralogic and paramoralisms

This series expands on the glossary entries included in Political Ponerology.

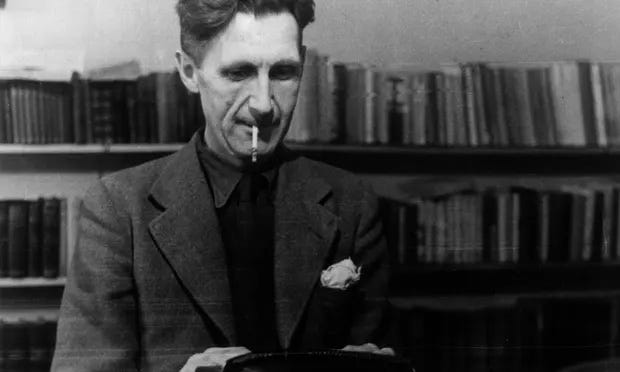

paralogic (paralogism, paralogistics): An illogical, false logic. A paralogism is a statement or argument intended to be persuasive that is fundamentally illogical. It can either be the result of conversive thinking or deliberate mendacity. Ideological propaganda is a form of paralogistics. It is ostensibly logical, but contains false premises, leaps of logic, and double standards. Paralogic acquires much of its persuasive force due to the presence of paramoralisms. Orwell captured the essence of paralogic in 1984: “War is peace, freedom is slavery, ignorance is strength.” James Lindsay defines ideological paralogic as “an alternative logic—a paralogic, an illogical fake logic that operates beside logic—that has internally comprehensible rules and structure but that does not produce logical results.”

paramorality (paramoralism): An immoral, false morality. Paramoralisms can take the form of slogans or suggestive insults (epithets, terms of abuse) with highly negative connotations. They are the means by which something good or neutral can be deemed evil or immoral, or something evil or neutral deemed good. For example, words with positive, neutral, or negative connotations can be transformed into the words implying the worst form of evil, e.g., traitor, counterrevolutionary, Jew, kulak, racist, sexist, transphobe, etc. Those under the influence of a psychopathological individual will often paramorally defend them and even approve of their behavior. If freedom is slavery according to paralogic, then according to paramorality, evil is good, and conscience is evil. James Lindsay defines ideological paramorality as “an immoral false morality which lies beside (and apart from) anything that deserves to be called ‘moral.’ The goal of the paramorality is to socially enforce the belief that good people accept the paramorality and attendant pseudo-reality while everyone else is morally deficient and evil. That is, it is an inversion of morality.”

When Lobaczewski introduces paralogistics he gives the example of “Austrian talk,” the tendency to distrust everything one’s conversational partner says—even the most mundane details, even when they’re telling the truth, and even when there is no good reason to doubt what they say. He also identified the Marxist ideological indoctrination of his university instructor as paralogistics. Simply put, it is bad thinking—the tendency to come to wrong conclusions using an ostensibly logical thought process. It does not compute.

Paramoralisms are moral inversions, emotionally laden statements that carry moral connotations and inspire those hearing them adopt the implicit moral stance and take the implied course of action. As Lobaczewski put it:

The conviction that moral values exist and that some actions violate moral rules is so common and ancient a phenomenon that it seems not only to be the product of centuries of experience, culture, religion, and socialization, but also to have some foundation at the level of man’s phylogenetic instinctive endowment (although it is certainly not totally adequate for moral truth). Thus, any insinuation framed in moral slogans is always suggestive, even if the “moral” criteria used are just an ad hoc invention. By means of such paramoralisms, one can thus prove any act to be immoral or moral in a manner so actively suggestive that people whose minds will succumb to such reasoning can always be found. (pp. 138-139)

I think of them in terms of several types:

Pejoratives. Lobaczeski gives as an example Lenin’s invective-fueled name-calling. Simply calling someone a “filthy traitor” is enough to blemish their character in the eyes of others, regardless of the facts.

Explicit inversions. Lenin also introduced a principle of anti-empathy, according to Gary Saul Morson. Schoolchildren “were taught that mercy, kindness, and pity are vices.” More generally, Ernest Andrews writes that totalitarian language’s “chief defining characteristic was the reduction of all reality … wherein the good equaled all things that were part of the ‘socialist/communist’ reality, while the bad equaled all things that, in some way or to some degree, stood opposed to the things ‘socialist/communist.’”

Implicit inversions. In this variation the moral principle stays relatively intact, but is misapplied. Someone using it may adopt the principle and manipulatively accuse another of violating it—even when the person so accused may in fact be exemplifying said principle. This is a typical psychopathic manipulation—the liar accusing the truth-teller of lying, for instance.

Demoralization

I quoted James Lindsay’s definitions in the above entries. He has since published a very nice New Discourses Bullets episode on demoralization:

With inspiration from Yuri Bezmenov’s use of the term as a phase of pathocratic political warfare, he identifies five types of demoralization, handily summarized in one of the YT comments:

Moral: can’t tell right from wrong (good/evil)

Perceptual: can’t tell real from fake (authentic/inauthentic)

Social: can’t tell who to trust (friend/foe)

Epistemic: can’t tell true from false (truth/lie)

Spiritual: nihilistic outlook (hope/despair)

Black Pill Goal: Induced dysfunctionality and dependency

Counter-Strategy: Moralization, optimism, and humor

This one concept—demoralization—encapsulates many central aspects of ponerology. You have paralogistics (epistemic demoralization), dissociative thinking more generally (including perceptual demoralization), paramoralisms (moral demoralization), and the loss of social capital and spiritual crisis characteristic of the disintegrative phase of secular cycles (social and spiritual demoralization).

All of this creates the conditions of dysfunctionality and dependency which allow psychopaths to gain levels of influence and power that were unthinkable during “good times,” which are characterized by relatively better capacities for logical and moral reasoning, and higher levels of social capital.

Semantic Entropy

Another helpful way of looking at this topic, which I recently came across, is

’s description of semantic entropy and its relation to political and legal entropy. In his recently published collection, FAQs on Reality vol. 2, he writes:Let’s use the phrase “semantic entropy” to describe linguistic disorder involving loss of information regarding word definitions. Then we may consider the possibility that legal and political entropy are functions of semantic entropy caused by the tortured verbal manipulations and legalistic language games of lawyers and politicians vying for wealth and influence at public expense. (p. 69)

Such doublespeak is a key feature of totalitarian language. The new definitions tend to be emotionally suggestive in nature, skewing in a particular direction for a particular purpose. As Lobaczewski wrote, “One should bear in mind that such an ability is characteristic of most psychopathic and paranoid individuals and that these statements are [also] paramoralistic in nature” (Ponerology, p. 209). Either that, or they are deliberately vague and blandly euphemistic.

Langan continues:

If we lose semantic information regarding the definition of a word, then this tends to dissolve the boundary of its definitive cell, and also the cells of any words whose definitions incorporate it; cells can split, merge, disappear, and change location in a way that warps the entire semantic network comprising their definitional relationships with other cells. (p. 70)

By extension, when intentionally employed by pathocrats, semantic entropy induces dissociative, paralogical thinking in others. If the words are corrupt—the content of thought—the process of thought itself becomes hopelessly confused, as premises become disjointed from their logical conclusions. Cognitive dissonance is resolved in a phantasm of ostensibly logical truth that covers over any conscious awareness of an uncomfortable truth or the entropic nature of language employed to banish it from the eye of awareness.

When public opinion succumbs to semantic entropy, and politicians then take the opportunity to freeze it in the form of law, legal and political entropy increase as a result. (p. 71)

Uberboyo on YouTube makes a similar point in his reading of Orwell (highly recommended, so please watch—there’s a George Carlin clip to entice you):

And once semantic entropy is frozen like this, institutions will tend to preserve the new entropic “order,” repressing any “negentropic” influences capable of reversing it. It becomes self-reinforcing.

But Langan doesn’t just point out the disorder; he defines what he means by a legitimate political order. And what he writes resonates well with what Lobaczewski has to say in both Political Ponerology and Logocracy:

What, then, is the “most orderly” political order? Where the proper purpose of any political order is to benefit society, it is that political order which maximizes social utility. Social utility is maximized when the ability and industry of the populace finds maximal constructive expression, which occurs when economic opportunity is widely distributed, creative freedom is unleashed, and noise from other sources – e.g., rampant elitism and economic strangulation of the middle class, and social unrest associated with such things as immigration policy – is minimized so that social stability is maintained and knowledge can be accumulated and productively applied without interruption, interference, or misdirection. (p. 66)

The most profound kind of social and political order is found only in a system which is consistent with human psychology and thus nonreliant on repression; when such a system gives way to repression, this order is lost and replaced with a false “orderliness” which is at odds with human nature and thus bought at the expense of a greater tendency toward rebellion and social breakdown. (p. 68)

Lobaczewski has much to say on this topic in Chapter 2 of Ponerology, and much of Logocracy (particularly on the principle of competence), but here’s how he sums it up:

A just social structure woven of individually adjusted persons,1 i.e., creative and dynamic as a whole, can only take shape if this process is subjected to its natural laws [i.e. human nature] rather than some conceptual doctrines [which are often paralogistic in nature]. It benefits society as a whole for each individual to be able to find his own way to self-realization with assistance from a society that understands these laws, individual interests, and the common good. (PP, p. 48)

When this natural order is allowed to unfold, it creates a socio-psychological structure to emerge, the human telos, which is implicit within humanity and its tonic diversity and variations of talents. This is the structure that gets degraded in disintegrative phases of secular cycles, helped along by semantic entropy, and deliberately induced by pathocrats.

He means socio-occupationally adjusted, i.e. matched to their level of competence.

It's long past time for a rectification of names. Death to all euphemisms! We must say what we mean, clearly, and with feeling.

While the devious use of words and "logic" is important in understanding the mechanics of ponerology, it operates at the level of the symbol, and thus is unsatisfactory when we look at higher levels of knowing. How do these lies creep into those higher levels? We need, eventually, some understanding of the situation that could result in at least a partial resolution of the problem of the psychopath.

For me, this arrived in the form of Hubbard's work. Others find solace in the findings of parapsychology or perhaps in the experiences of some particular person who had an NDE then returned to life transformed.

We must believe that spiritual life, by definition, exists above the level of biological life, and that addressing the spirit, or Spirit, can ultimately revive a being, give them a new sense of hope and purpose, and perhaps even some day free the psychopath from his or her demons.

The ultimate dire image of any horror movie is that of the "hero," sorting through piles of data until he begins to understand what is really happening, suddenly blindsided by a surprise attack and unable to defend himself because he lacked the skills he needed to put that understanding into practice.

As my own biological life slowly burns out, I face that image more and more starkly. I do not have sufficient spiritual skill to get even my own friend to look with a fresh eye, feel with a fresh heart, think with a fresh mind. And so my "friend" today can become my enemy tomorrow and see me as little more than an object needing to be annihilated.