Logocracy - Chapter 18: The Executive

Administering the state through political and regional government

Chapter 18 covers the executive branch of logocratic government, i.e. the head of government, his cabinet, and the ministries that administer the state’s political, social, and economic functions. Exclusively partisan government is incompatible with natural law: the executive must represent all citizens. As for its head—the prime minister, or president of the council of ministers—he should choose his ministers based on their qualifications, not their party affiliation or other anti-merit-based criteria (e.g. nepotism, DIE).

Skills, and less so party affiliation, should be the deciding factor in assigning a person to ministerial positions. A logocratic government may consist of members of different parties and non-partisans, and should be decided by consensus.

Lobaczewski chalks up the problems with democratic executives (e.g. frequent changes of administration, cabinet crises, lack of cooperation with parliament) to “the excessive role of party affiliation and the ease with which devious and selfish people get into the legislature and other authorities.” Various logocratic mechanisms are designed to mitigate these problems.

Ministers should have talent, education, and previous professional and political experience. Key subject areas include political science, sociology, economics, and the biohumanities. As some commented on a previous chapter, some of these fields are seemingly hopelessly corrupt. Lobaczewski acknowledges the problem, noting that it was precisely these disciplines which suffered the most under communism:

It should be noted here that these are precisely the disciplines which have been most discriminated against under the pathocracy and which have been led to considerable degradation. Their scientific restoration is a necessary condition for the construction of an improved system.

Again, the principle of competence is the sine qua non of logocracy.

However, education in these fields is not enough. Potential ministers ideally should have a specific professional degree, work experience, “followed by a second study in a field related to politics,” as well as parliamentary rights and some lower-level political experience.

Lobaczewski recommends psychological realism when it comes to ministerial performance. The hyper-attentive focus on minor gaffes in American politics—followed by near-obligatory resignations—is not realistic. In fact, it “discourages and drives away many worthy people.” Rather, “In entrusting a man with high office, one should first see his character, talents, and education, and then let him mature in practice.” To foster this, new ministers without experience as MPs will shadow their predecessors before taking their positions.

A logocratic executive will consist of a prime minister and three types of ministers or secretaries: political, representative, and regional. The PM will be chosen by parliament from among candidates put forward by the same institutions who do so for the senate; parties will put forward their best candidates, not just their party leaders.

The PM will then appoint political ministers approved by parliament, to a limited number of ministries (e.g. Interior, Foreign Affairs, Defense, Treasury, Industry and Trade, Agriculture, Communications, and Health and Welfare).

Representative ministers (as with their counterparts in parliament) will be elected by their respective independent powers, i.e. Justice, Science and Education (both approved by the president), and the Directorate of Social Goods (whose minister, approved by the PM, will work with the Minister of Industry and Trade).

Regional ministers, representing a geographical area encompassing a number of states or provinces, will be appointed by the head of state with senate approval, usually from among former ministers. In Poland, for instance, there would be 5 to 7 such ministers.

It would be the duty of the regional ministers to know the affairs of their regions well and to represent their needs to the government. They would be an inspecting and mediating body, controlling the correctness of all public institutions of the region.

In states of emergency, regional ministers would meet with their political counterparts, acting as a “factor of prudence and experience” and advising ministries within their expertise. In a cabinet crisis, representative ministers will keep their posts, and vacant political ministerial positions (including that of PM) will be filled by regional ministers.

The government will notify the head of state of each meeting and its subject matter, and the head of state will have the ability to call on the regional ministers, and to chair the session, if he deems it necessary. As for dissolving the government, this will be

… by a decision of the government itself, by a vote of no confidence passed by a simple majority of both houses of parliament, or by a similar vote passed by a higher qualified majority of the senate. The president will have the power to dissolve the government based on a lower qualified majority in the senate itself.

Finally, ministers should be relatively autonomous, consulting with each other when necessary, and deciding collectively (by clear or qualified majority) on important issues.

If such a convincing majority proves unattainable, regional ministers should be called in. If even this does not lead to a mature decision, the government should appeal to parliament. Therefore, the ratio of votes of ministers in important matters of state should be public.

Chapter 18: The Executive

The government of a country is the body that administers its political, social, and economic functions. It should therefore act within the framework of the law, for the good of all the citizens of the country and its role in the world. It is therefore not compatible with natural law that the government should become an organ of one party that has won an election. Therefore, the Westminster principle—winner takes all—could not be adapted to a logocratic system.

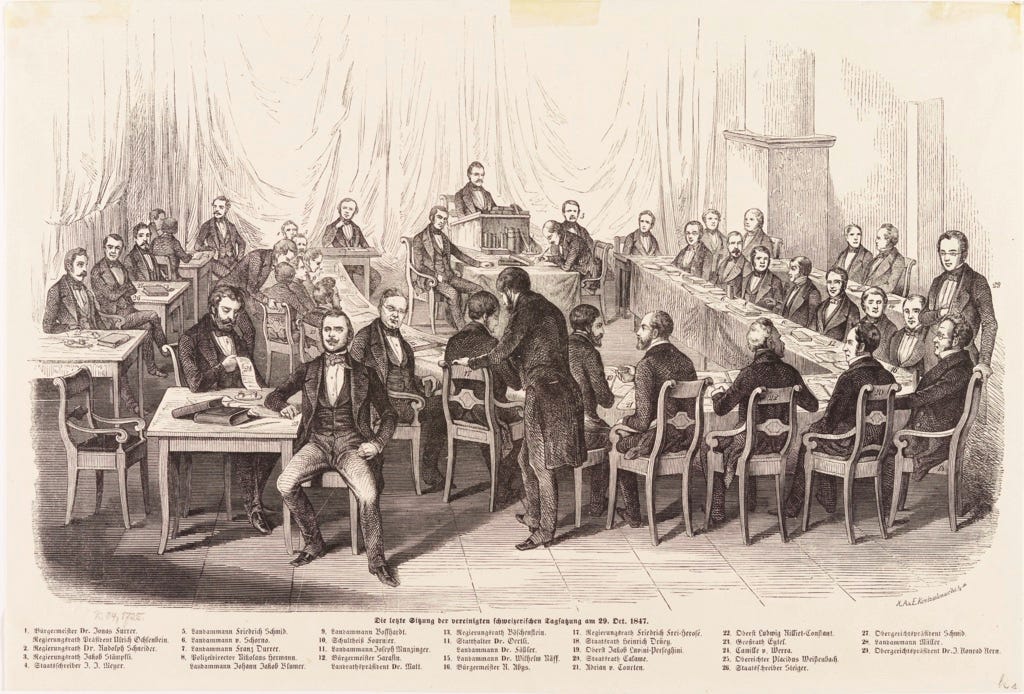

It is not without good reason that the government of the United States of America is called “administration” and not “government,” and its head feels himself to be the president of all Americans. In choosing his ministers, he looks above all for people with the best possible qualifications. Especially in the lower positions, there remain many who are members of the opposite party or of no party at all. In Switzerland, the government consists of representatives of all the major political parties and operates on the principle of consociational decision-making. Nevertheless, it is not an inefficient government.

In all three of these countries, England, the U.S., and Switzerland, the set of moderating factors is the long tradition of independent self-government that nourishes all-party political sanity. However, even in such countries we can see that things are already beginning to break down there. The Swiss system has proved to be the most reliable and this should be taken into account in our further considerations.

Logocracy must become a system capable of efficient action in all countries, including those which have recently become independent, or those which have experienced a historical cataclysm and are therefore lacking in moderating factors, traditions, and experience. It is therefore necessary to find a way of forming a government which, thanks to its foundation in the natural characteristics of societies, is always capable of acting efficiently and righteously.

The too frequent changes of ruling teams, the protracted cabinet crises, the difficulties of cooperation between government and parliament, which bring so much harm to democratic nations, are due to the now well-known weaknesses of democracy, among them the excessive role of party affiliation and the ease with which devious and selfish people get into the legislature and other authorities.

A logocratic system will seek to eliminate the causes of these defects at all levels of its organization, through theoretical principles we already know, through psychological realism, through experience with democratic government, and through a properly drafted constitution. Widely promoted understandings of the demands placed on human beings by the highest offices of the land or legislative work, and an understanding of the people who undertake such responsibilities, should become criteria for finding optimal solutions.

Participation in governing the country requires a high level of aptitude, adequate scientific preparation, and the necessary political experience. Therefore, the development of appropriate studies: political science, sociology, economics, and biohumanities, will follow from the basic premises of logocracy. It should be noted here that these are precisely the disciplines which have been most discriminated against under the pathocracy and which have been led to considerable degradation. Their scientific restoration is a necessary condition for the construction of an improved system.

On the other hand, it can also be observed that people who have received education in the above-mentioned fields, but do not have adequate experience in practical activity, later show a tendency to doctrinal radicalism and to overlook many social realities in their reasoning. The ideal background for a minister should be a specific profession, work, and experience, followed by a second study in a field related to politics. This was the background of Lady Margaret Thatcher, who first studied chemistry and gained some work experience, and then took up sociology. Therefore, the minimum requirements for a ministerial candidate should be a professional degree, professional work, parliamentary rights, and some experience in political activity. The final choice should belong to the prime minister, parliament, or senate. The council of wise and the president can help.

Skills, and less so party affiliation, should be the deciding factor in assigning a person to ministerial positions. A logocratic government may consist of members of different parties and non-partisans, and should be decided by consensus.1 Therefore, the newly elected prime minister will call on all parties and legitimate institutions to put forward suitably qualified candidates.

Those who take part in governing the country gradually acquire the necessary experience in this art. Although the whole system of logocracy will tend to limit experimentation on the people, the phenomenon of learning from mistakes can never be completely eliminated. Therefore, minor mistakes should not be the cause of resignation, because the one who replaces the one removed will also be a fallible human being. The American habit of keeping track of every gaffe of those in chief positions stems from the psychologically unrealistic assumption that there can be an infallible human mind. This discourages and drives away many worthy people. In entrusting a man with high office, one should first see his character, talents, and education, and then let him mature in practice. A logocratic system should function satisfactorily in spite of known human deficiencies, rather by knowing them.

For these and similar reasons, the logocratic system will follow the practice of prolonged entry into office. A person elected or appointed to an office will accompany his predecessor as his successor for a period recognized by law or practice. This will not be required of current MPs. These beliefs and practices should reduce the frequency of change in government positions, extending the life of those officials. Constitutional provisions should contribute to the good selection of people.

The people who make up the apparatus of government usually have no more influence on the history of a nation than some outstanding people who achieve goals in the fields of science, culture, technology, or economics. Logocracy will be the system of society and it will decide the future of the nation by its sovereignty, moral and mental values, integrity of conduct and work. Only in the period of the emergence of the state as an independent entity and the formation of a more perfect system should the government play a leading role, doing so for the future of the nation. So we are looking for solutions that best meet the above requirements. And here is a proposal:

The council of ministers would consist of the president of the council of ministers, and three types of ministers called: political, representative, and regional ministers. They would be appointed in different ways.

The president of the council of ministers will be chosen by parliament, by simple or qualified majority, from among its own candidates or those put forward by the logocratic association, political parties, and independent powers, and who have gained the approval of the council of wise. The political parties will then be forced to put forward candidates of their most able people, not just their leaders. In a republican system, an elector who has been elected by a simple majority will be approved by the president. If not approved, there will be a re-election. A logocratic parliament, made up of people prepared for their duties, with a significant minority of members and senators who do not belong to any party but are elected for the value of their minds and characters, will tend to elect people with similarly good qualifications, often not representing any party. This will ensure better decisions for the country than a premiership of party leaders.

The elected and approved prime minister will appoint political ministers who will be approved by the parliament or only by the senate. It seems expedient to limit the number of these ministries as to the Interior, Foreign Affairs, Defense, Treasury, Industry and Trade, Agriculture, Communications, and Health and Welfare.2 A smaller number of ministries with a wider range of powers seems a cheaper and more efficient organization. Two representative ministers, Justice and Science and Education, will be elected, by independent powers, and will be approved individually by the head of state. The Council of Social Goods will choose a deputy representative minister to work with the minister of industry and trade, and will be approved by the prime minister. The political ministers and representatives will constitute the “political government” of the state.

Regional ministers would be appointed individually by the head of state with the approval of the senate. These positions would be given mostly to experienced people, often former ministers. They would represent in the government the affairs of the regions of the country called ziemiami (“lands”) in Poland. For this purpose, Poland would be divided into 5 to 7 such regions with borders following a certain historical tradition—usually three provinces each. This would be the number of these ministers. It would be the duty of the regional ministers to know the affairs of their regions well and to represent their needs to the government. They would be an inspecting and mediating body, controlling the correctness of all public institutions of the region. They would be accompanied by inspection offices such as the NIK,3 labor inspection, and others, as well as some institutions related to science. Their offices would be located in the capitals of these regions, not necessarily in the capital of one of the provinces, but in a town convenient in terms of communication. They would be summoned to the capital by the prime minister individually, or for plenary cabinet meetings, or by the head of state in the event of a cabinet crisis.

In a normal condition of the country, a political government composed of political ministers and representative ministers would operate, and the regional ministers would perform their duties in the regions. In need of difficult, contentious, or historical decisions, a plenary government would meet with the regional ministers, in which the latter would be the factor of prudence and experience. Each regional minister would have some kind of advisory position to one or two political ministries, according to his skill and experience. In Poland, a regional minister would be an advisory deputy prime minister. They would have insight into the activities of these offices and would be kept informed. In the event of a cabinet crisis, only the prime minister and political ministers would be subject to resignation. Representative ministers would remain in their posts. The functions of prime minister will be assumed by the Minister of Greater Poland. Orphaned ministries will be taken over by regional ministers, some supervising two of them. In this way many of the harmful effects of a protracted cabinet crisis will be avoided. The situation in which the apparatus of executive power will be in the hands of prudent and experienced persons will be conducive to the resolution of the difficulties and the peaceful formation of a new, efficient political government.

The president of the state will be notified of every meeting of the government and its subject matter, and will have the power to elevate its importance by calling upon the regional ministers. The republican constitution may provide that the president will then have the opportunity to take the chair of the session. The government will be dissolved by a decision of the government itself, by a vote of no confidence passed by a simple majority of both houses of parliament, or by a similar vote passed by a higher qualified majority of the senate. The president will have the power to dissolve the government based on a lower qualified majority in the senate itself. The resignation of a representative minister will require a separate individual procedure set out in the constitution. The resignation of a regional minister will be granted by the head of state on the proposal of himself or the senate, or possibly the council of wise.

Individual ministers should have sufficient autonomy to make their own decisions or to consult with other ministers. In matters of greater importance, the government should decide collectively by a clear or qualified majority. If such a convincing majority proves unattainable, regional ministers should be called in. If even this does not lead to a mature decision, the government should appeal to parliament. Therefore, the ratio of votes of ministers in important matters of state should be public.

A logocratic government, acting in cooperation with such a parliament and on the basis of independent authority, would certainly be more efficient in its work and more accurate in its decisions than can be achieved in a democratic system. At the same time, possible excesses of government power, which have been the cause of misfortunes in the past dramatic century, will be much less likely. Nevertheless, such a government will not be weak or limited in its powers.

Note: This work is a project of QFG/Red Pill Press and is planned to be published in book form.

HK: A reference to consociationalism or consensus democracy, in contrast to majoritarianism. In Switzerland, it is called a concordance system.

HK: That’s eight ministries. The U.S., by contrast, has 15 departments, including Justice (a function of the judiciary in a logocracy), Transportation, Energy (these two would fall under the independent Directorate of Social Goods), Education (an independent power), Housing and Urban Development, Labor, Veterans Affairs, and Homeland Security (a redundant department).

HK: The Supreme Audit Office, akin to the U.S.’s Government Accountability Office.

To be President (Prime Minister) or Cabinet Member over a federation of 50 states containing over 300 million people is a huge responsibility to say nothing of the potential workload. I don't see how any human being could be expected to perform in this role competently, let alone sanely.

Yet we can always hope that a few among us exist who could bear such a task with skill and success.

I would only point to a few related matters that might have to be worked out to make this a realistic expectation for even the most accomplished human being:

1) The organization being run (in this case the administrative branch of the federal government) must be sanely organized. A sane organization follows a few basic rules of which I will only mention two.

a) Any senior should only have four or five direct juniors.

b) Sub-sections of the group should follow the exact same patterns and policies that the full group must follow.

To me this means dividing the country into regions and sub-regions. Maybe five regions each with two or three sub-regions. The Federal Reserve, for example, is divided into 12 districts.

2) A chief executive should be highly emotionally stable. You can't have the guy throw some fit that results in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people (Putin? Stalin? ...Lincoln??).

In my world this can only be accomplished through extensive spiritual counseling from my church. Thus, bringing secular executives up to my standards for "competence" is currently beyond possibility, unless we somehow manage to elect an OT8 Ls completion (forgive the jargon; you can look it up if it makes a difference to you).

This may be the best original reason for democratic elections. This essentially crowd-sources the sanity test. It's a big ask of any population, but perhaps better than leaving it up to psychiatrists or psychologists. Perhaps Lobaczewski would disagree?

"The president of the council of ministers "

Is this the "leader" of the gubment or is there no individual leader?

If not, if there is no "executive" in person, then does this not lend itself to confusion needless and bureaucratic?

Or is the "prime minister" the leader?

Regardless, without an individual leading, restricted accordingly, just begs for gubment inefficiency.

Local is better. From the ground up.