Logocracy - Chapter 3a: Man, Society, State

The importance of the differentiation and variation of human talent

All this creates a complex mosaic of talents that gives human society multiplied creative possibilities. The diversity of talents is a great gift of God and nature to humanity. The good and the future of nations depend on how we respect and manage these abilities.

I’m breaking up this chapter into two parts. The first provides a brief description of some of the aspects of human nature Lobaczewski thinks essential to take into account when designing and implementing a logocratic state system. For those who have read Political Ponerology, thus recapitulates the ideas in Chapter II of that book, specifically its description of the emotional-instinctive substrate, the social nature of man, basic and general intelligence and their distribution, individual talents, and socio-occupational adjustment.

Lobaczewski describes how all these variations come together to create a healthy social structure. He also provides a rough picture of appropriate occupational positions for different IQ brackets, though noting that societies can be either too rigid or too lax concerning this.

Therefore, in a modern social system … the proper adaptation of individuals, their opportunity for self-realization in creative activity and their right to seek their own way in life, should constitute both the aim of the social system and the criterion of the rightness of its action.

Chapter 3a

The basic element of society is the human individual, who as recently as the 1930s Dr. Alexis Carrel could call “the unknown.”1 Today, however, the vision of this great naturalist is being fulfilled, as the knowledge and understanding of man progresses with each passing year.

However, man always remains an extraordinarily complex being, especially in his psychological state, which can never be understood or described by means of our common psychological worldview, even if it is refined through literary, philosophical, and religious reflection. In order to understand man well, we must make use of the objective system of natural and psychological concepts which modern science is gradually developing.

It follows that all the social and political doctrines on the basis of which the ancient and modern systems of countries were built, or in the name of which revolutions broke out, were based on inadequate conceptions of the personality of man. The simplistic schema of this personality, which overlooks many essential properties of our nature and the considerable range of psychological causality that operates within us, has been handy for the formulation of laws and for energetic administrators. It finds defenders among ambitious people. The consequence of this is that in current systems the subjects of the law—the judges and defendants—are sometimes a kind of philosophical or legal mannequin which plays certain roles, whereas the consequences are borne by living people.

From such a state of affairs even more radical simplifications come easily, even caricaturing the human personality, which we encounter in totalitarian, nationalist, or class doctrines. Such doctrines, convenient for propagandists and leaders, have justified systems of power which in fact had different roots and causes, often of a psychopathological nature.

Progress in the psychological understanding of man, which began about 120 years ago, has now reached such a level that we can rely on it to overcome such phenomena. This creates the first opportunity in the history of our civilization to build a social and state system that would become a homeland for real people, as we are, with our complex nature and interpersonal diversity. The customs, laws, and organization of such a country would come from an understanding of human personalities, their values and weaknesses. They would take into account the creative role of psychological differentiation that occurs among individuals of the species Homo sapiens. In order to be able to sketch in the following chapters the concept of such a system, let us briefly but objectively list the most important characteristics of human personality as modern science sees them. We also believe that the coming times will bring further development of knowledge in this field and its refinement.

Animal psychology teaches us two basic laws of nature. The higher psychologically organized a species is, the longer is the period of immaturity of its representatives in proportion to the whole life. That is why man has the longest childhood. The same law holds true within the species and this is why a highly gifted person matures later on average than a mediocre one.2 Secondly, the higher the mental organization of a species, the greater the inter-individual mental variation. Thus our species reveals the greatest extent of this differentiation, which occurs at all levels and in all structures of the human personality.

A phenomenon common to all animal species and to man is the existence of a phylogenetically derived and hereditarily transmitted instinctive substrate of mental life. The content of this substrate, as a product of many thousands of years of phylogeny, is characteristic for a given species. The instinctive substrate of the human being is a set of emotionally colored inborn reactions, formed in the species living socially since its prehistory. This substrate inspires the activities necessary for the development of the human personality. We carry within us the basic responses of social nature, containing its wisdom and its errors which have been known for generations. Therefore, the human personality cannot develop normally outside of a suitable human environment. It must acquire psychic material from other people in various ways in order to transform it into its own personality. Nor can it find the meaning of life outside of human society and its bonds.

But no instinctive substrate, as a product of the species’ phylogeny, can be perfect in its responses. It fails particularly dangerously in situations that, due to their apparent similarity to certain stimuli, trigger responses encoded in our instincts as para-adequate responses. Such responses lead animals, their packs and swarms, to extinction.3

In humans, the instinct is somewhat less dynamic and more plastic, which opens the possibility of rational control over its manifestations. Nevertheless, also in humans we meet dramatic difficulties caused by such para-adequate instinctive and emotional reactions. Good upbringing should aim at working out a harmonized cooperation between the instinct and the intellect, so that the human being will benefit both from the wisdom of nature coded in his instinct and also from the ability to control his involuntary reactions.

This instinctive endowment of man shows discernible inter-individual differences. People differ especially in its dynamism or its ability to give way to rational control. There are also differences in its richness of content and its sensitivity. Nevertheless, in the vast majority of people, this apparatus is normally rich and typically human.

Only a small percentage of people (2-3%) show discernible defects in this substrate, with “gaps” in its spectrum, impaired performance as if skating on sand, or in its asthenicity or weakness. Such people grow up to carry a sense of their difference from the world of normal people. They have an impaired ability to produce a common psychological worldview and, consequently, to understand the meaning of social customs. They bring many difficulties to society and are often treated as the culprits.

On the basis of the instinctive substrate, through its interaction with the surrounding human world and in the process of upbringing, basic intelligence develops, also called emotional intelligence, always fused with instinctive emotionality. This allows us to sense the state of other people and psychological situations, to develop a common psychological worldview and a sound moral sense, to intuit the value of respect for other people and of good conduct, and thus to find ways of behaving tactfully. Although there are natural variations in these abilities, due to both heredity and upbringing, this basic intelligence is widely distributed in society. Only a similarly small percentage of people exhibit significant deficits in this area, which can be found at almost all levels of intellectual performance, with the exception of the highest levels of giftedness. A marked deficit in this basic intelligence is essentially a psychopathic deviation.

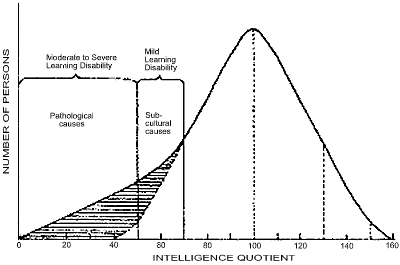

The intellectual layer of our intelligence is quite differently distributed in societies. It shows the greatest qualitative and quantitative diversity of human abilities. Normal man represents all levels of ability, from mental sluggishness to excellence. All states worse than what is here called sluggishness are caused by various pathological factors, most often by traumatic brain injury. The distribution of these talents in a given country is represented by a curve resembling a Gauss bell curve, but somewhat irregular because its left arm representing lower talents is bent to some extent, due to the presence of pathological factors.

We refer to the lowest level of ability as mental sluggishness. A normal person with this level of aptitude can master the curriculum of about five grades of elementary school. After that, his mind more readily accepts practical life skills. Even so, such a man may have a good basic intelligence that allows him to develop a socially reliable character. However, he will always have a sense of needing support and care from someone more powerful. This is why ancient social systems gave the weak a better chance of social adaptation than modern democracies do. Care for people with inferior mental capacity is practiced today in all civilized countries, so it will certainly be developed also in the system proposed here, which has deeper humanistic assumptions.

People with abilities close to the average values (IQ=94-107) comprise up to 50% of the population of various countries.4 Such people form the core of the mass of voters in democratic countries today. They are mostly people with a specific occupation as workers, farmers, or others. In a modern society they may have graduated from a vocational school, which has given them an appropriate education in a popularized manner, but based on sound knowledge.

This stratum, already politically conscious and active, shows intelligence sufficient to judge accurately the characters of those educated persons whom it encounters in the life of the community and in its workplaces. They know and understand many technical issues. They represent an understanding of practical realities, and a sensitivity to social and moral issues. To a large extent, they are the voice of common sense. Their talents and skills fail, however, when they lack direct contact with the people they need to know, or in more difficult matters such as economics or international politics, and especially where there are psychological and moral problems caused by the activities of people who are not completely normal mentally. When their skills fail, selfish motives and emotions, the inductive action of collectives, and the ambitions of groups and their leaders come into play.

A psychological analysis of the talents of people of this class, supported by experience in the perception and use of vocational school curricula, indicates that their critical political sense could be greatly improved by an adequate popular education, but so could a vocational school curriculum based on good knowledge. This indicates to us how the problem of the political activity of persons of this class of aptitude can be solved in the new better system. For this social group—because of its size, level of prosperity, and ability to organize—plays and will continue to play an important role in social and political life. The necessary preparation for it should therefore be built into the educational system of the country. The solution to this problem will be proposed in the chapter on the principle of competence.

Individuals with superior talents are a minority in any society. Unfortunately in Poland there has been a tragic counter-selection as a result of the extermination activities carried out by the Nazis and Bolsheviks, and the mass emigration of the intelligentsia to Western countries. Compared to other countries, our giftedness curve is flattened, representing this impoverishment. Only time, natural eugenic processes, and the spread of an appropriate eugenic morality can correct this deficit. In the proposed system there will be an institution that patronizes such pursuits.

People of the highest level of giftedness constitute only a few per thousand of the population of nations. Nevertheless, these people endowed with incisive intelligence constitute such an important factor in the life of any nation that their relegation to a position of social maladjustment and the suppression of their voice and cultural-creative role, inspiring progress in various fields or serving as accurate critics, make the normal functioning of society—its cultural, economic and political development—impossible. Thus, a nation’s future depends on how it is able to recognize these people, acknowledge their role, and respect them. It should be mentioned here that the lack of this virtue of respect for one’s own wise people was one of the causes of the tragedy of our Polish history.

But no state system can be based on faith in the existence of brilliant people or in the genius of a leader. For exceptional human creativity is most often the product of a coincidence of two circumstances, when an individual of the highest talents is forced at an early age by the circumstances of life to cooperate in overcoming real difficulties, often under unusual conditions. Such people develop the necessary accuracy of thought, realistic grasp of reality, perseverance, and the ability to pursue new paths. A person with similar talents, but brought up in the comfort of a settled life, may be a good scientist or politician, but will not develop this innovative path. Governing a country requires both a certain stability and novelty. Both of these types of people should therefore find their way into public activity. However, societies should never forget the tragic lesson of history, when the belief of leaders in their own genius, or of the masses of people in the genius of a mentally aberrant leader, proved to be pathological phenomena with tragic consequences.

To date, no psychological test has been developed to assess human giftedness in a sufficiently objective manner. Tests do not sufficiently capture basic intelligence. In addition, the higher up on the intelligence scale one goes, the greater the error in these indications.5 Therefore, the psychologist must correct these indications accordingly, which requires individual skill. In life, experience makes similar corrections. However, data obtained in this way allow the assessment of a person’s talents with sufficient reliability for the analysis of his social and occupational adaptation.

To the variety of human talents sketched above, we must add numerous talents and specialized abilities. Some people are gifted with the ability to capture an unusually large amount of data in their field of attention. Others have an unusually capacious and durable memory. We know people who have a talent for figurative reproduction or color composition, who are aesthetically sensitive, who are gifted with musical hearing, or who have a talent for sensing and observing psychological phenomena. All this creates a complex mosaic of talents that gives human society multiplied creative possibilities. The diversity of talents is a great gift of God and nature to humanity. The good and the future of nations depend on how we respect and manage these abilities. Human talents constitute a fundamental social capital, which must be used purposefully and sparingly, as we do with expensive raw materials or energy, but with due respect. For this reason, the management of talents must never be treated as a purely private matter.

In this psychological differentiation, the potential, implicit structure of society must already be perceived, which should be realized as a matter of concern for those who have undertaken to govern a country. The fundamental aim of the individual, in the realization of which the state and society must be of assistance, is the self-realization of his potentialities through appropriate socio-occupational adaptation. Such adaptation gives to the individual satisfaction and better success, and to society optimal benefits from his work. It should be emphasized that a normal person feels the situation of his correct adaptation as social justice towards himself. Defective adaptations, on the other hand, are sometimes the cause of bitterness and difficulties on every social scale. So let us look at the typical errors of this adaptation.

A person with a qualitatively inaccurate and inferior adaptation in relation to his own talents is always aware of it, though it is rarely affirmed by those around him. Therefore, the understanding and recognition of such a state by a psychologist is always a step in the right direction. Such a person is easily frustrated, so he changes his profession or job, learning the new one easily. The learning period gives him an opportunity to engage his talents. But since his work does not engage his abilities, he takes his mind off it and goes into the world of his interests and dreams. As a result of this distraction, he is more likely to make mistakes and to cause accidents. Although such people sometimes make some innovations, they generally do not do the job better than a worker of merely sufficient ability. An employee who is more intelligent than his supervisor is easily drawn into ambitious conflicts with him. In such a situation, however, these people do not properly develop a healthy appreciation of the limits of their abilities. Thus, it seems to them that they could cope with tasks much more difficult than their real abilities allow, for example, governing a country. Thus, the dream of changing the social system in which they were subjected to such a harmful maladaptation, often by means of violence, finds fertile ground among such people. Such individuals thus constitute a factor of social discontent or revolutionary turmoil.

However, the temporary adaptation of a person below his talents and abilities allows him to accumulate practical experience, triggers his ingenuity and efforts to get out of this situation. This makes creative sense and is used to varying degrees in different countries. In the U.S., employing young academic graduates in labor positions is a common practice with good results.

Individuals who, through wealth, political, doctrinal, or racial privilege (such as some blacks in the U.S.), have reached positions where their talents prove inadequate in the face of tasks and responsibilities, begin to be demonstratively preoccupied with matters of lesser importance while overlooking those that are significantly more important but more difficult. There is a characteristic component of theatrics in their behavior. They begin to play a role of what they unfortunately cannot be. Their way of thinking becomes conversionary or dissociative,6 and a decline in the correctness of their reasoning can be empirically demonstrated after only a few years in this position. These individuals prove to be prone to an uphill battle against better able workers, which contributes to the under-adaptation and frustration of the latter. Inflated socio-occupational adaptation results in a life of constant psychological strain. Such people are more likely to suffer from the so-called diseases of civilization, and their bodies age faster.

In the model of a sick society, the over-emphasis on socio-occupational adaptation by some and the under-emphasis by others are two sides of the same coin. In such a situation, the waste of human talents and abilities—this basic social capital—is reflected in all areas of life, culture, science, technology, economics, and politics.

Man develops his mental and spiritual capacities best when his education and occupation correspond to his real talents. The better the social and occupational adaptation of individuals in a country, the more correct is its socio-psychological structure. If this problem is solved in a near-optimal way, there is order in the country, and the creativity of society in every field will be the richest. The economy of exploiting human talents is the basis of all economics in the broad sense of the word. Therefore, in a modern social system, the best that can be built, the proper adaptation of individuals, their opportunity for self-realization in creative activity and their right to seek their own way in life, should constitute both its aim and the criterion of the rightness of its action. For all this contributes to the formation of a living and active psychological social structure, that is, society as such.

Modern psychology and occupational science can provide helpful methods for this purpose. It is also possible to calculate correlation coefficients of occupational adaptation. Particularly in a country that, as a result of the imposition of pathocratic rule, has lost its historically created social structure, the use of the achievements of modern science to contribute to its restoration seems not only a temptation to use new skills, but may also prove to be the only way out. With regard to the scale of general intelligence, the correct adaptation could be presented roughly as follows:

IQ Aptitude Index

≤93: Workers apprenticed to practical work. [HK: Roughly 32% of the population]

93-107: Qualified laborers with vocational schooling. [~36%]

107-114: Foreman and foreman workers. [~14%]

114-122: Technicians and elementary school teachers. [~11%]

122-132: Employees with higher education and academic studies. [~5%]

132-136: The intellectual elite—scientists and politicians. [~1%]

≥136: Heads of state and exceptional artists. [≤1%]

It should be emphasized here that a system better than a democracy would have to incorporate the necessary devices so that the highest offices of state would be in the hands of persons with the requisite talents and scientific training. Concepts of such arrangements will be given in the following chapters.

Note: This work is a project of QFG/FOTCM and is planned to be published in book form soon.

HK: Carrel (1873-1944) was a French surgeon and biologist whose most famous book was titled Man, the Unknown (1935).

HK: A common theme in the work of Dabrowski, who associated this extended period of maturation with multilevel disintegration, as well as phenomena like “positive immaturity” or “psychoneurotic infantilism.” He cites Michelangelo as “One of the best examples of extended and unfinished maturation” (Dabrowski 1972).

HK: For example, the ant death spiral, where the ants’ usually effective pheromone system encounters a situation in which their instinctive response is inadequate or inappropriate, causing them to die unless diverted off their established course.

HK: Using a standard deviation of 15 points, 50% of the population fall between an IQ of 90 and 110.

HK: Standard IQ tests are only accurate up to about an IQ of 160. They can’t capture a one-in-a-million intellect, for instance.

HK: Translated as “conversive thinking” in Political Ponerology.

Of many thought provoking paragraphs, this one stood out for me:

"The simplistic schema of this personality, which overlooks many essential properties of our nature and the considerable range of psychological causality that operates within us, has been handy for the formulation of laws and for energetic administrators. It finds defenders among ambitious people. The consequence of this is that in current systems the subjects of the law—the judges and defendants—are sometimes a kind of philosophical or legal mannequin which plays certain roles, whereas the consequences are borne by living people".