Logocracy - Chapter 8: The Principle of Public Sovereignty

Popular sovereignty is an ideological fiction and contradicts human nature

Lobaczewski is sympathetic to modern democratic forms of government, to a degree. They have at least proven themselves capable of supporting relatively stable and workable systems. And in that sense the notion of “popular sovereignty”—that true authority is held by “the people”— has stood the test of time. However, to the degree that this and related ideas deviate from human nature, the problems arise. In this light, the notion of popular sovereignty is more a political ideology or naive belief than it is an actual principle rooted in concrete reality.1

In fact, all democratic systems restrict the franchise, whether with an age limit, a requirement for citizenship, or additional criteria. The question is how restricted it should be, because when it is unrestricted, democracy tends to devolve into “the semi-secret rule of organized minorities.” For Lobaczewski popular sovereignty should be limited to a psychologically normal, rational society. He sees this as a natural law and right.

We shall regard pressures to limit the exercise of this natural law in favor of individuals incapable of fulfilling their civic duties as measures designed to weaken the social organization of nations in order to exploit them.

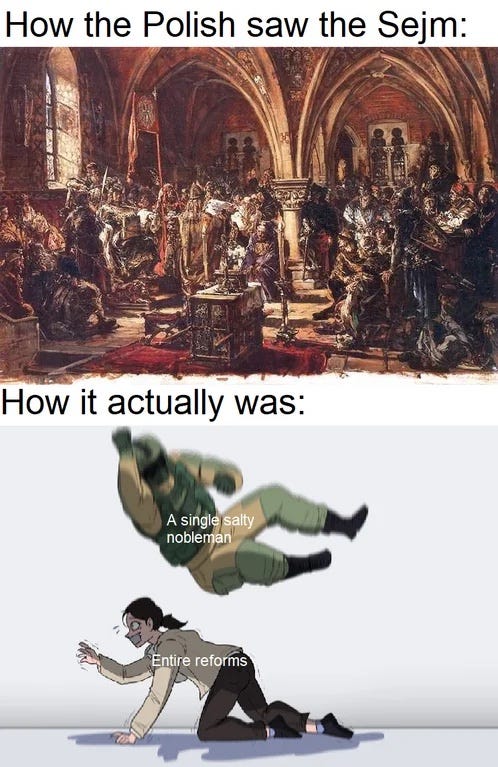

Such individuals include those “incapable of prudently exercising the rights and fulfilling the duties that flow from democratic principles” for various reasons (e.g. age, mental ability, morality). Foremost among them are the ponerogenic minority of individuals with various personality disorders, who act in democratic societies as a kind of liberum veto on the majority of rational society. Logocracy seeks to mitigate their influence on politics as much as possible.

This principle, along with others like that of competence (dealt with in the next chapter), should be realized “through the dissemination of good knowledge of social, political, and economic matters.” This would create a greater role for those citizens of high intelligence and common sense who avoid involvement in the typical party system and whose voices are overshadowed by the mainstream parties. This “prudent center” should have the right to nominate non-party candidates for all elective positions.

A democratic system tends to elect and place in positions of authority people who are not of the highest caliber, and a party system often places in its leadership people with a tendency to be doctrinaire and extreme in their views.

The Principle of Public Sovereignty

The principle of a democratic system, which assumes that the sovereign is the people and not the ruler or any privileged group, has already partially passed the test of time and experience. Countries where it has been reasonably respected have proved capable of governing themselves, but not without characteristic difficulties. These difficulties arise from a certain naive idealism of the doctrine, which does not take into account the psychological realities already discussed, which exist in every country. In the form in which we find it in modern democracies, the principle must be regarded as a political ideology that is not entirely consistent with the laws of nature. Both scientific reasoning and practical experience teach us that if we grant the right to vote to all people who are too young or incapable of understanding political realities, then such a democracy ceases to operate in accordance with the above principle and degenerates into the semi-secret rule of organized minorities. Thus, it ceases to be a democracy. Therefore, if we want to build a better system, this problem must be skillfully solved.

We must recognize as a natural law the sovereignty of a rational society which is capable of exercising sound judgment and prudence. We shall regard pressures to limit the exercise of this natural law in favor of individuals incapable of fulfilling their civic duties as measures designed to weaken the social organization of nations in order to exploit them.

We already know that in every society of the world there is a certain numerically limited minority of individuals who, because of their mental deficiencies, mental deviations, and moral failings, are incapable of prudently exercising the rights and fulfilling the duties that flow from democratic principles, guided by an understanding of the good of the whole and even of their own. This minority, easily inspired by demagogy, can be a decisive factor, tipping the scales in votes. It can also have a distorting effect on much more numerous groups, pushing them towards ponerogenic phenomena. Particularly in nations with less political experience and general culture, this pathological faction exerts an excessively dangerous influence on the whole of social life. If this phenomenon cannot be eliminated altogether, it must be limited to safe proportions.

The action of this minority is reminiscent of the Polish liberum veto, which limited the right of a reasonable majority of the Sejm (legistlature) to make decisions consistent with the good of the nation.2 The liberum veto grew out of an idealistic interpretation of ancient laws, detached from social and psychological realities, and thus out of what can be considered the opposite of the spirit of logocracy. It limited the sovereignty of the noble democracy in favor of factors that were politically or psychologically alien to that society. The results were lamentable. A naive interpretation of the principle of national sovereignty works similarly, limiting that sovereignty itself. The theory and practice of logocracy cannot accept this.

For all these reasons, the principle of the sovereignty of the nation must in the logocratic system be refined and transformed into the principle of the sovereignty of the logocratic society. This will happen through appropriate corrections, resulting from objective knowledge of the nature of societies, and introduced into a number of system solutions. As a consequence of this, a more mature and clearer social opinion will enjoy greater respect from the authorities, and at the same time the differences in attitudes between different social groupings will be somewhat mitigated. These improvements will be realized in the most natural way possible, through the dissemination of good knowledge of social, political, and economic matters, through the widespread application of the principle of competence, and through the operation of a politically neutral organization called a logocratic or civic association. These arrangements will be discussed in the relevant chapters.

A democratic system tends to elect and place in positions of authority people who are not of the highest caliber, and a party system often places in its leadership people with a tendency to be doctrinaire and extreme in their views. Citizens with balanced convictions, which may be a consequence of their greater intelligence, common sense, and education, are thus overshadowed. As they are inclined to see in each political party its values but also its doctrinal extremes and errors, they avoid formal involvement with any of them. So they choose to work organically and creatively, and seek to serve society, themselves, and their families along the way. When they vote, they tend to be guided by the personal qualities of candidates rather than by their party programs.

Such citizens constitute a part of society quantitatively more numerous than those already discussed and qualitatively more valuable. The activation of this prudent center for the needs of social and political life follows from the most general assumptions of the logocratic system, as one that values prudent and critical minds. Therefore, the constitution of every country with this kind of system should provide for the existence of a social organization that will gather citizens who do not belong to any political party, but who represent a wide range of moderate views. This organization will have the right to nominate candidates for all elective positions, and will do so on the basis of recognition of the value of their characters and their abilities. We may call such an organization a “logocratic” or “civic” association. The detailed tasks of this association will be discussed in Chapter 13 of this work.

Other solutions that implement the principle of sovereignty of a logocratic society will be discussed in the following chapters.

Note: This work is a project of QFG/FOTCM and is planned to be published in book form soon.

HK: For a more in-depth treatment on the topic of sovereignty in general, and popular sovereignty in particular, see Michael McConkey’s The Managerial Class on Trial.

From Wiki: “Many historians hold that the liberum veto was a major cause of the deterioration of the Commonwealth political system, particularly in the 18th century, when foreign powers bribed Sejm members to paralyze its proceedings … In the period of 1573–1763, about 150 sejms were held, about a third failing to pass any legislation, mostly because of the liberum veto. The expression Polish parliament in many European languages originated from the apparent paralysis.”

Yes I'll order the book too.

It's an outstanding chapter.

It's unwavering in standing up for truth.

Citizens must be responsible and stand up for themselves if they wish to participate in a logocracy, painful as that is to hear, to protect the people and true civilization.

I ordered the book today. That is an interesting concept there at the end. I might borrow it.