Neurotics Gone Wild: The Asthenic Personality

A chapter from Polish psychiatrist Antoni Kepinski's book, "Psychopathies"

This series expands on the glossary entries included in Political Ponerology.

asthenic psychopathy: Asthenia (from the Greek a- without + sthenos strength) was generally considered a nervous or mental fatigue or weakness characterized by passivity, low energy, inability to enjoy life, low sensation threshold, irritability, and unstable moods. In Western psychiatry, diagnosis of asthenic personality disorder eventually split into dependent and avoidant (also passive-aggressive) personality disorders, though these bear only a passing resemblance to the disorder Łobaczewski describes. The ICD- 11 equivalent for avoidant personality disorder is a combination of negative affectivity (anxiety, avoidance of situations judged too difficult), detachment (avoidance of social interactions and intimacy, see schizoidia), and low dissociality (reversed self-centeredness, low self-esteem). The type described in Cleckley’s Caricature of Love seems much closer to Łobaczewski’s.

When discussing the “ponerogenic” personality disorders, Lobaczewski focuses on the most serious, the ones that contribute the most to pathocracy. I’ve written about many of them: psychopathy, frontal brain damage (i.e. secondary psychopathy, pseudopsychopathy, etc.), schizoidia, and paranoid personality disorder. But he mentions others in passing which also play a role—basically all the other personality disorders, including anankastic/obsessive-compulsive (covered here recently in an excellent article by Martin Grady), hysterical/histrionic, and, this article’s subject, asthenic/dependent.

The connection between asthenic and dependent PDs isn’t very clear in Lobaczewski’s work. Reading one of the books he cites, Antoni Kępiński’s Psychopathies, makes the connection becomes a bit clearer. (I have included the full chapter on this disorder below.) To sum it up, asthenics are hopelessly neurotic—so neurotic that they have a completely distorted self-image, finding fault everywhere in themselves, even when others do not see these faults (because they do not really exist). For Kępiński, the psychasthenic is tortured because of the vast gulf between his ideals or potentials and what he sees in himself, which can never live up to them. He is incapable of “lifting himself up,” as it were, to his ideals, which are detached from reality. He lives more in his dreams than reality. Psychasthenics are pathologically inhibited, indecisive, constantly dissatisfied with themselves and others, and feel little if any joy (or love). Their personality structure is always incomplete.

Dabrowski, in contrast, placed asthenia on a spectrum, from neurasthenia on a low level (mainly manifesting in physical lack of energy) to psychasthenia on a higher level (the spending of mental energy; depression). Dabrowski defined it as “A type of psychoneurosis characterized by lowered biopsychic tonus, especially in regard to primitive [e.g. practical] functions and adjustment to actual reality. Psychasthenia is characterized by feelings of inadequacy, obsessions, anxieties (especially existential), depressions.” While the inner milieu of neurasthenics is fairly shallow, psychasthenics experience “multilevel” disintegration, i.e. the inner division between higher and lower aspects of oneself, an awareness of potential structures that may be realized, and the realization of those potentials. (Dabrowski characterized Proust, Kafka, and Zeromski as psychasthenics.) Psychasthenia acquires a much more positive connotation in Dabrowski due to its association with examples of high developmental potential and personality development.

As for Western psychiatry, here’s how asthenic PD was defined before the morph into dependent PD:

ICD8: Characterised by inadequate response to intellectual, emotional, social and physical demands. Such individuals are generally unable to adjust to specific situations such as marriage, home life or occupation, and exhibit lack of self confidence, indecisiveness and emotional dependence.

ICD9: Charactcrised by passive compliance with the wishes of elders and others and a weak inadequate response to the demands of daily life. Lack of vigour may show itself in the intellectual or emotional spheres; there is little capacity for enjoyment. Synonym: Passive, Dependent, Inadequate.

DSM2: Characterised by easy fatigueability, low energy, lack of enthusiasm, marked incapacity for enjoyment, and over-sensitivity to physical and emotional stress.

The paper above used factor analysis to condense 13 symptom, life history, and psychological test items down two 2 factors: anxiety proneness and inability to cope with stress.

Lobaczewski’s description of asthenic PD includes the following traits and tendencies, starting with those most similar to the above formulations:

asthenic and hypersensitive

no great deficit in moral feeling and ability to intuit social and psychological dynamics

somewhat idealistic

masks inner world and aspirations from others (somewhat akin to a “mask of sanity”)

less vital sexually (sometimes verging on asexuality)

superficial pangs of conscience as a result of their faulty behavior

shallow nostalgia

easily avoid consistency and accuracy in logical reasoning

better at adjusting to social life than psychopaths, especially via the arts

literary or artistic expressions are “disturbing” (“they insinuate to their readers that their world of concepts and experiences is self-evident”)

some enjoy demonstrating their “strangeness”

psychological worldview to some extent childishly distorted, so their opinions about people cannot be trusted

anti-psychological attitude:

Their behavior towards people who do not notice their faults is urbane, even friendly; however, the same people manifest hostility and a perfidious, preemptive aggression against persons who have a talent for psychology or demonstrate knowledge in this field. … The more severe cases are more brutally anti-psychological and contemptuous of normal people. … Their dreams are composed of a certain dramatic idealism similar to the ideas of normal people. They would like to reform the world to their liking and combat its errors, but are unable to foresee the more far-reaching implications and results. (pp. 118-119)

Lobaczewski acknowledged that he may have been conflating different types, nomologically speaking. That’s what it looks like to me. I think he saw certain asthenic traits in a type that was simply more sinister than your average neurotic psychasthenic. That’s why I made the connection to those authors Cleckley describes in Caricature of Love. Read the excerpts I included here to see the connections. Those types were characterized by antisexuality (e.g. sadism and masochism), shallow ideals and pangs of conscience, contempt for normal people, physical and mental “ennui” or lassitude (i.e. asthenia), and disturbing artistic creations and ideas.

But there may be something else going on here too. In a pathocracy, asthenics may become victims of their own inability to realize potentials and their dependency on the external world for validation and structure. Perhaps in a normal world they would be better off, but pathocracy offers a simulation of structure in which they can find meaning.

Lobaczewski gives the example of Dzerzhinsky, founder of the Soviet Cheka (secret police). He quotes the following from a letter of his (with Lobaczewski’s notes in brackets):

If I had to start life all over again, I’d do exactly the same: it’s organic necessity, not the dictates of duty. [Feeling of being different.] I have one thing which keeps me going and bids me be serene even when things are so very sad. [Shallow nostalgia.] That is an unshakable faith in people. Conditions will change and evil will cease to reign, and man will be a brother to man, not a wolf as is the case today. [Vision of a new world.] My forbearance derives not from my fancy, but rather from my clear vision of the causes which give rise to evil. [Different psychological knowledge.]

Psychopaths, according to Dabrowski’s theory, are incapable of any real inner ideal, any separation within oneself. The only ideals they chase are in the external world, whether that be the next high, the next score, or a pathocratic world in which they can do whatever they want. Severe asthenics, by contrast, only have ideals (inner and external), but they are unattainable. This leaves them vulnerable to finding their place in a system that just mimics ideals, like a pathocracy. Such a system provides a vehicle for the realization of their dreams, but one that perhaps never quite lives up to those dreams.

So perhaps a guy like Dzerzhinsky really was disturbed by the evils of the world, however detached from reality he otherwise may have been. Unable to effect any inner transformation of his own, he sought the manifestation of his ideals in a system which gave the appearance of righting wrongs, creating a new world. Dependent on the ideological and communal structure of Marxism-Leninism, he found the realization of a structure he could not manifest in himself. Essentially, he was conned (and conned himself) into believing the Soviet solution was the salvation he was looking for.

Feeling unsure of themselves, perhaps asthenics flock towards a system the claims certainty and the solidity of principles they do not find in the normal world. It gives them a sort of pseudo-strength which they otherwise lack. But since their potentials are never fully realized, always incomplete, they lack the practical experience and knowledge to be able to tell the difference. They “fight evil” while participating in it. And perhaps these types made up a portion of the revolutionaries that ended up getting purged by their more pathological counterparts?

With that said, here is how Kępiński characterized “the psychasthenic type.” The chapter is long, so for those strapped for time, I have bolded what I think are the most important or insightful points, most having to do with psychasthenics, but others regarding hysterics and paranoids and other assorted topics.

The Psychasthenic Type

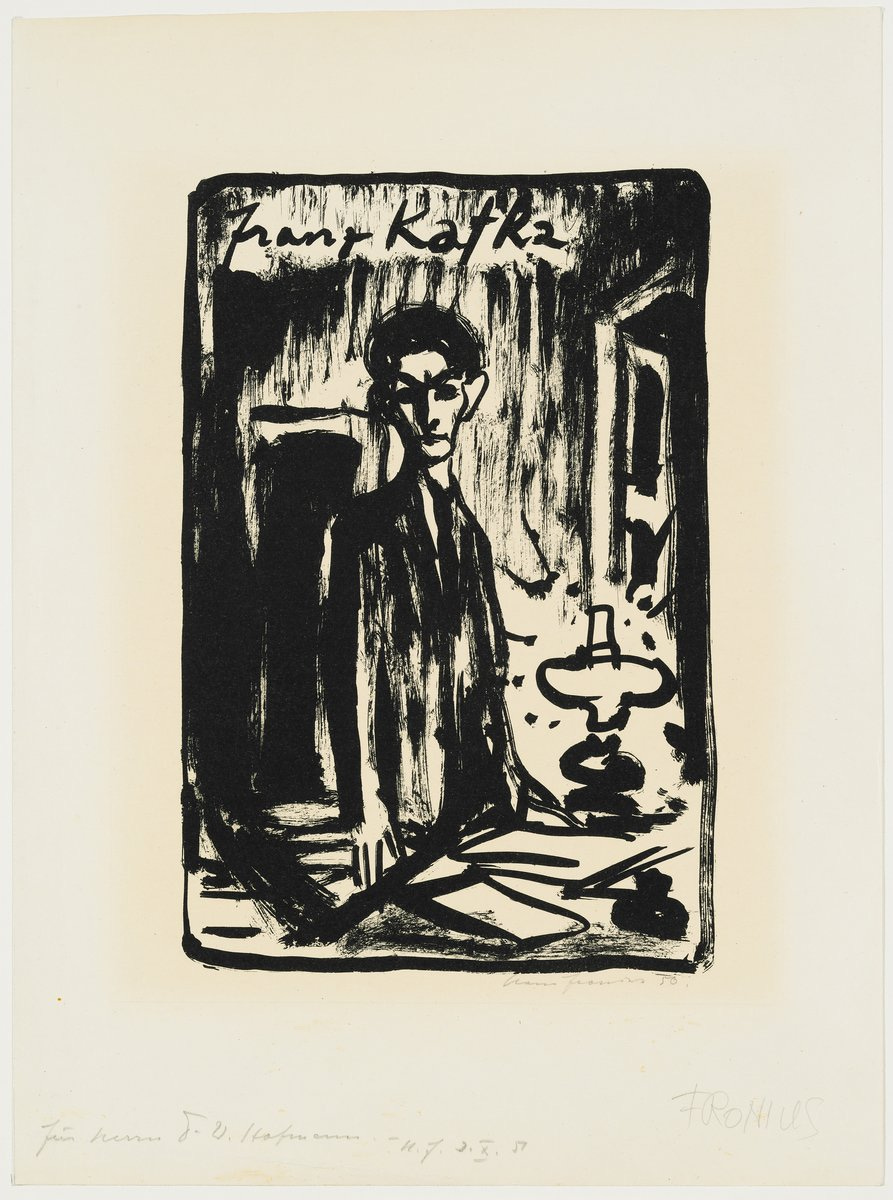

By Antoni Kępiński, from Psychopatie (Warszawa: PZWL, 1977), translated with DeepL

The psychasthenic1 is seemingly the antithesis of the hysteric. While the hysteric loves the theater, wants to shine, impress those around him, always be the center of attention, the psychasthenic would gladly sink into the ground, put on a cap of invisibility; he goes through torment when he finds himself in the center of attention of the environment; then he does not know what to do with himself, everything is in his way, his own hands, legs, his own voice. He does not want to reflect his surroundings, he dresses in grey, he would like to go through life unnoticed, although deep inside he dreams of great theater, he would like to become someone great, famous, a man about whom everyone talks, but he hides these dreams deeply.

The hysteric easily realizes his potential functional structures; depending on the situation, he changes like a chameleon. There are no impossible things for him, he can play different roles: in love, angry, indignant, delighted, etc. From one role he easily jumps to another, even its opposite. His hesitation is short, and he makes a decision before he has time to think about it. He cannot bear the burden of potential functional structures, he tries to realize them immediately, and when this is impossible, they are pushed out of consciousness. The psychasthenic, on the other hand, continues to hesitate. For him, a decision is weighed down with an extraordinary burden of responsibility, sometimes he has to be pushed from outside, because he would never make up his mind on his own. When he does decide, he often regrets his decision, thinks about it for a long time, feels remorse, and would like to change it. His typical trait is esprit d’escalier (belated wit, untimely response)—it is only when he is on the stairs that he remembers what he should have said and how he should have acted a moment ago in the living room. He finds it extremely difficult to implement functional structures. He is always dissatisfied with his performance, with his acting. The social mask makes him uncomfortable. His self-control system is extremely developed, he constantly feels the critical gaze of those around him; whatever he does seems to him bad, awkward, everyone is better than him, he is the worst. It is necessary to constantly give him courage and self-confidence.

An overgrowth of the self-controlling system in a psychasthenic has an inhibiting effect on activity and the decision-making process. Potential structures are sometimes extremely overstimulated, but they are poorly realized and the psychasthenic is usually dissatisfied with them. As a result, the probability index of the realization of functional structures is low for him, while it is high for the hysteric. For the psychasthenic, everything is unlikely, too difficult, impossible. He prefers to withdraw from life rather than move forward. He often treats life as an unpleasant duty, he lives because he was born and has to live. Life itself does not attract him very much, he enjoys only the praise of those around him, it gives him confidence, it can motivate him to make efforts.

The hysteric discharges his feelings easily (“storm in a teacup”). Psychasthenics tend to stifle their feelings. Sometimes, when too many negative feelings accumulate in him, an explosion occurs. The surroundings are then amazed that this quiet and calm person discharges himself in such a violent way. In psychiatric jargon, one speaks of the “sthenic spike” of psychasthenics. They generally give the impression of being soft, yielding, gentle, but there are certain sectors of their psyche where they are tough and implacable.

Psychasthenics usually have their own conscious value system, but are usually afraid to show it to the world around them. This system is often too idealized and difficult to realize. The psychasthenic, for the sake of peace of mind, sometimes prefers to accept the value systems of his surroundings, although internally he rebels against them. He feels fear of the social environment; social condemnation is the greatest punishment for him, therefore he tries to fit into his environment, to be like the others, not to stand out, not to be noticed, not to be either the first or the last. As with the hysteric, the question that torments him most is “what will others think of me.” Only, if this question stimulates the hysteric to the realization of potential functional structures, the psychasthenic is clearly inhibited by this question, he stifles potential functional structures and tries to realize only those that are fully approved by the environment. This is why he feels an inner hypocrisy, because he sometimes thinks something different and has to do something different. In the case of the hysteric, the surroundings rather sense his hypocrisy, he himself is often unaware of it.

At work, the hysteric is usually irresponsible and avoids effort, while the psychasthenic tends to be over-responsible, exerts his strength to the maximum and has the impression that everything he does is wrong; he has no self-confidence, the environment must encourage him, strengthen his self-portrait. Psychasthenics, unlike hysterics, are good workers, you can rely on them, they are dutiful, ambitious, “meek and humble of heart.”

If in erotic relationships the hysteric is most attracted by the conquest of a partner, then the psychasthenic is afraid of this very conquest, does not trust his strength and attractiveness, and usually he is rather the conquered than the conqueror. Often in his erotic life there is also a large discrepancy between dreams and reality; his love is more easily realized in an idealized world than in reality. This is related to his typical difficulty in realizing potential activity structures. He always has the feeling that what has been realized is much worse than what was in potentia (in the sphere of possibilities or hopes). For this reason, love often remains in the realm of dreams, and what he has managed to realize often brings disappointment, dissatisfaction or even repulsion, especially when he has been forced to realize love in some way. This is not so rarely the case since, as mentioned, he is conquered rather than a conqueror.

This “forced” attitude is quite typical of the psychasthenic and applies not only to his erotic life. One sometimes has the impression that he is “forced” to live at all; he lives out of a sense of duty, life seldom really pleases him, pleasures are burdened with a sense of guilt, he is not very attracted to the world because he still has the impression that his realization in this world is somehow false, wrong, there are too many discrepancies between potential and realized functional structures. The hysteric, it seems, clings to life more strongly than the psychasthenic. The right to preserve one’s own life is for the hysteric the supreme principle of the hierarchy of values, which could not be said of the psychasthenic; in fact, one does not know what keeps him alive, perhaps a sense of duty. The psychasthenic is often detached from life; on the contrary to the hysteric, he feels better among potential functional structures than among realized ones.

According to Pavlov’s typology, he is more often a thinker type than an artist type, i.e., the processes of the second signaling system predominate in him over the processes of the first system. The processes of the second system are further from the threshold of realization than the processes of the first system. A potential functional structure, in order to become a realized structure, must pass through the receptor-affector “ends” of the reflex gap. In the hysteric, everything happens as if on the periphery of the reflex hatch, his image of the world is usually sensual, and his activity in the world is mainly motor (i.e., all those forms of activity that clearly manifest themselves in the surrounding world). In contrast, in the psychasthenic, activity is concentrated in the middle section of the reflex arc, often not involving the receptor and effector ends. Therefore, the psychasthenic is more of a thinker type than an artist.

This predominance of the second signaling system over the first in psychasthenia is related to the predominance of potential over realized functional structures. This is because potential structures occupy the central section of the reflex hatch, and realized structures occupy the marginal receptor-affector sections. Decision difficulty results from overloading the central section of the reflex arc; when there are too many potential structures, it is difficult to decide which one to choose. The decision process becomes cumbersome. Fluctuation and uncertainty become characteristics of such a person.

Associated with hesitation and uncertainty are certain anankastic traits that are not uncommon in psychasthenics. Typical of obsessives, rumination, repetition of the same action (checking) is sometimes due to the difficulty of decision. Unable to make a decision on his own, the psychasthenic often resorts to a ritual, to a decision imposed on himself, and regardless of his internal state (i.e. potential activity structures) and external situation, he performs what is “ordered,” what is in his opinion a necessity—ananke, even if it is a completely senseless activity. In this activity, however, there is a belief in its magical power, that it will undo the “evil” associated with the process of decision-making, which is too difficult for the psychasthenic.

As it seems, there are fundamental differences between psychasthenic and obsessive personality profiles, but the tendency to anankastic forms of behavior is common to them. In anankastic syndromes the element of perseveration is characteristic, the same thought, activity, experiences are repeated many times. Perseverative tendencies can occur when there is difficulty in making a decision. When it is possible to decide on this or that functional structure, it may happen that a completely random structure is chosen; the very fact that it has been chosen makes it a constantly recurring choice. This is because it has broken through the resistance of the decision process. A not uncommon trait of psychasthenics is stubbornness; once they have embarked on a path, it is difficult to bring them back from it, they cling to it, for though the path may be wrong, it relieves them of the anxiety and doubt of deciding. Here the difference between the hysteric and the psychasthenic becomes clearly apparent. The hysteric still realizes something new, still enters upon new paths, because the process of decision does not present him with difficulties.

Janet, the creator of the notion of psychasthenia, gave it a rather broad scope, believing that at the root of psychasthenia lies incompletude, i.e. a kind of unfinished personality structure, which in today’s terminology would correspond best to an immature personality. If in the hysteric the immaturity of personality is manifested primarily by a lack of responsibility and a predominance of “I take” over “I give” in emotional relationships, then in the psychasthenic it manifests itself in an underdeveloped self-portrait. The psychasthenic is unable to look at himself objectively. Although the hysterical person’s self-image is usually distorted, he or she is usually satisfied with it. In the case of psychasthenics, the gap between the idealised self-image and the real one is so large that it is impossible to reconcile the two images with each other. The psychasthenic wants to be different than he really is, he is constantly dissatisfied with himself, and even the approval of his environment, to which he is particularly sensitive, does not change his disapproving attitude towards himself. One gets the impression that his self-control system is constantly tuned to no, to criticism.

It is difficult to say where this excessive self-criticism comes from, especially since psychasthenics are often approved of and praised by their surroundings from childhood. So it cannot be explained by a too harsh social mirror. It seems that the reason lies in an excessive discrepancy between potential and realized structures. The psychasthenic is as if overwhelmed by his possibilities, so that whatever he manages to accomplish is too small and paltry in comparison with what he thinks he could and should accomplish. In every person there is a gap between the idealized (potential functional structures) and the real image of oneself (realized structures). This gap forces a person to constantly improve himself; thanks to it, individual evolution takes place. In the case of psychasthenics, however, this gap is too large, so that instead of stimulating them to self-realization, it often inhibits them.

In contact with psychasthenics, one often gets the impression that they are inhibited. The environment sometimes tries to reverse this, to give them self-confidence. Sometimes one would like to get them drunk and see if they don’t loosen up when drunk and how they will behave then. Indeed psychasthenics under the influence of alcohol often become uninhibited, freer and see themselves in a better light.

In Pavlovian terminology, we could speak of a predominance of inhibitory processes in psychasthenics, and a predominance of excitatory processes in hysterics. The self-image is formed on the basis of the realization of potential activity structures. We must constantly check ourselves in action on the surrounding world. Without this, our self-portrait would lose the features of reality, we would feel our own unreality. In psychasthenia, depersonalization and derealization symptoms are not uncommon. The hysteric realizes himself too easily, hence the impression of theater, game, hypocrisy. It is too difficult for a psychasthenic to realize himself, hence the impression of understatement, concealment, a mask under which something unknown is hiding.

Life requires constant activity, one must constantly try out one’s own abilities, prove oneself in action. One cannot live only with potential functional structures, because such a lifestyle ends with an explosion—potential functional structures are thrown out and become the psychotic reality of the patient. It is worth mentioning that the pre-disease silhouette in schizophrenia usually has very distinct psychasthenic features. The question arises, why do psychasthenics have significant difficulties in realizing their potential functional structures? Why is there such a preponderance of inhibitory processes in them?

One would first have to answer the question of what is the motor of human activity. From a biological point of view, these drivers are two biological laws: the preservation of one’s own life and of the species. In psychasthenia these laws have a weaker power of influence. The psychasthenic is as if loosely connected with life. He lives, as it were, on the margins of life. He is unable to fight for life, he gives up easily, and he is unable to love. This weak “fixation” on life is certainly determined to a large extent by genetics, but also environmental factors are not without significance. Man’s biological laws are under strong pressure from social and cultural laws, which may be related to the fact that man’s information metabolism takes precedence over his “energy metabolism.”

A variety of environmental factors can cause a person to gradually lose confidence in himself, and with it his attachment to life. Attachment to life goes hand in hand with self-confidence, with the belief that one will emerge victorious from the struggle with the environment. Self-portrait and life dynamics are closely related. This is evidenced by the fact that all mood swings, i.e., life dynamics, are primarily reflected in the self-portrait. It is difficult to say which environmental conditions work favorably and which unfavorably on the self-portrait and life dynamics. Sometimes too good conditions, a maternal environment that lasts too long, dehumanize a person, deprive him of the will to expand into the surrounding world, if only out of fear that he will never be there as well and safely as in the maternal environment. Bad environmental conditions, inadequate maternity in the family environment can become the cause of breakdown, loss of self-confidence, and with it the will to live.

Psychasthenics have relatively stronger emotional ties to their father than to their mother (this observation, however, would need to be confirmed by more detailed research). The emotional relationship with the mother often determines the emotional color of further life. The mother is a kind of representative of the surrounding world, and the stronger the emotional relationship with her, the stronger the bond with life. The father, on the other hand, is the representative of the normative side of life, and when the emotional connection with him is strong, this side of life will be predominant in the individual—the sense of social norms, duty, etc., while the direct connection with life will be relatively weak. These are, however, very hypothetical generalizations. We do not yet have a clear enough picture of the life histories of people belonging to the various typological classes to be tempted to create a typology based on a longitudinal (life history) cross-section, although such a typology would be the most rational.

Psychasthenics often painfully feel a lack of connection with life. They complain of a chronic lack of joie de vivre, a life of obligation, its greyness, its lack of pleasure. Love of life is certainly a quality that gives life its flavor and color. It is difficult to live without loving life. Psychasthenics are often condemned to just such a barren life. If they seek very much the approval of their surroundings, it may also be because this approval stimulates them to live. By improving their self-portrait, their self-confidence increases, and thus their will to live increases as well.

Psychasthenia means exactly “weakness of soul” (asthenos—weak). Psychasthenics in difficult life situations, however, can sometimes behave very bravely. During war they were among the bravest soldiers. They are able to fight stubbornly for their hierarchy of values. So what is their “weakness of soul”? They feel fear of people, fear of life, they look for support in the environment, its approval, because they do not feel sure of themselves. If in the case of hysterics the need for approval (“what will they think of me”) results from the lack of a stable system of values, then in the case of psychasthenics it is a consequence of a weak connection with life.

The two basic biological laws are weakly fixed in the nature of the psychasthenic. In the hysteric the second law works poorly and he is not fully capable of love; in the psychasthenic both laws fail. Hence his need to seek support from his environment. If the hysteric frequently changes his hierarchy of values and has several of them at the same time, it is because he does not really need them. The most important problem for him is to stay afloat in life at all costs, and so the first biological law is exposed. The psychasthenic does not have this “grip,” he is loosely connected with life and this is probably what his “weakness of the psyche” consists in.

For him value systems are important because they give meaning to his life. Whoever does not cling to life on a natural basis, i.e. the two biological laws, must cling to it on the basis of artificial values, such as a sense of duty, one’s mission, some ideals, etc. The value system plays an essential role in the formation of decisions. It stimulates action, i.e., the change of potential activity structures into realized structures, and the selection of potential activity structures for realization depends on it. Biological systems are usually stronger than social and cultural systems. For example, hunger is a stronger factor in the value system than social forms associated with eating. In psychasthenics, the lack of a strong connection to life (weak action of both biological laws) causes their value systems to be weak, hence their weak realization rate of potential activity structures (they live more in dreams than in reality) and hence their difficulty in making decisions. For the human hesitation of self—cogito—increases as one moves away from animal, i.e. biological, positions. Biological imperatives are hard and ruthless, often operating on the basis of automatisms, without the participation of consciousness. They constitute the core of human personality, i.e., its fundamental hierarchy of values. In psychasthenics, this core is weak and therefore the name is apt.

This name must always be kept in mind when treating psychasthenics. The first goal in dealing with psychasthenics is to try to strengthen them. We can strengthen the other person first of all by improving his self-portrait. When he feels accepted by his social environment—even if this environment is only our person—then it is easier for him to face the surrounding world, it is easier for him to transform potential functional structures into realized structures. For the realization of a potential structure depends to a large extent on the likelihood that it will be accepted in the social environment. We generally reject those potential structures that have little chance of acceptance. Only structures based on a very strong value system—such a strong system is most often the biological system—can be realized even with a low probability of acceptance. The psychasthenic does not have a strong value system and therefore must rely on the acceptance of the environment.

With acceptance, the likelihood ratio of the realization of potential activity structures is increased. What was previously only in potentia is now at least partially realized. Thanks to this, the psychasthenic begins to live less in dreams and more in reality. Acceptance weakens the inhibitory effect of the self-control system. Feeling accepted, a person becomes less critical towards himself, and more easily throws out (realizes) those potential structures that he would keep in himself if he did not accept them. The realization introduces functional structures from the individual world into the common world. If any of our experiences becomes externalized—be it in the form of words, motor activity, facial expression, gesture, creative activity, etc.—then by the very fact of externalization we cease to exist.—It becomes a part of the noosphere, i.e. man’s cultural environment, as opposed to the biosphere, his natural environment.

Before any decision to transform a potential functional structure into a realized one, the probability of its acceptance in the human community must be taken into account. For this reason, information metabolism is always social in nature. Even functional structures par excellence biological have their social setting. It suffices to mention how this “setting” affects the forms of food intake, sexual life, etc. The feeling of being accepted by one’s environment is transferred to functional structures—according to the principle “if I am accepted, so is what is mine,” if I am accepted, then what I say, do, etc. will also be accepted. The probability of acceptance increases, and with it the probability of realization.

In psychasthenics, the probability coefficient of realization is low, there is a significant predominance of potential functional structures over realized ones, which does not have a positive influence on human development and in extreme cases can lead to psychotic realization. The pressure of potential activity structures is so great that they break down the boundary separating the inner and outer worlds and the potential structures become psychotic reality. That is, they do not realize themselves in the “bright” space, common to all people, but in the dark, psychotic space, which, although it is external, is not common, because what is thrown into it from the inside has no social “setting,” is a purely individual value, and thus incomprehensible to the environment, “other.” Therefore, the moment of calculating the probability of acceptance by the social environment is important in the decision-making process. Without this probability, the functional structure, despite its externalisation, does not acquire a social character. Information metabolism loses its essential feature, i.e. its social character. Information becomes strictly private and thus mostly incomprehensible. For man understands first of all what is “public.” The intimate, own part of the sign (information) is mostly inaccessible to him, except of course for the information which is created by himself.

Thus, without considering the probability of acceptance, man is condemned to dialogue with himself, since no one else can understand him. Information metabolism ceases to be an exchange of information, since this exchange becomes one person. In this view, psychosis can be seen as a temporary interruption of human communication.

The above discussion was intended to raise awareness of the role of social acceptance in human life. Without it, the information metabolism, which is an essential attribute of life, especially human life, can be disturbed or even interrupted.

If the peculiar tragedy of the hysteric is that his greatest desire in life generally does not come true, because he is not accepted by his surroundings—then the psychasthenic, fortunately, does not experience this kind of tragedy. As if following the evangelical principle “he who exalts himself will be humbled” etc., the social environment humiliates the hysteric and exalts the psychasthenic. Perhaps in this different attitude of the social environment to hysterics and psychasthenics there is a hidden harmony which has been created between the individual and the environment during centuries of evolution. As has been attempted here, the hysteric has his point of support—this is the first biological law, while the psychasthenic is devoid of this point, he is weakly connected with life, and while the hysteric can finally do without the approval of the environment, the psychasthenic cannot.

Psychasthenics are liked above all for those qualities that hysterics are deprived of, that is, for modesty, reliability, dutifulness, diligence. Hysterical and psychasthenic types are predominant in Polish society. The Polish hysterical type corresponds most strongly to what Brzezicki described years ago as the skirtotymic type (from Gr. skirtao—I dance); it is basically a noble type—the Polish “Zastaw się a postaw się”—the polonaise, Somosierra, the lancer’s charge on tanks, Polish sejmikowanie, Polish liberum veto and the so-called Polish Wirtschąft [“Polish economy,” i.e. chaotic and anarchic], a strange mixture of virtues and vices. The Polish psychasthenic is like a type of Polish peasant, quiet, peaceful, hard-working, not disturbing anyone, sometimes only showing his sthenic spike; then the good Polish peasant scares with the image of Jakub Szela [leader of the Polish peasant uprising of 1846]; he is stubborn and tough in hard life conditions. This strange decomposition of our society into people who talk and those who work has persisted for centuries despite changes in living conditions, economics, political system, etc.

This would be an example of the persistence of social structures; even though times have changed a lot, the nobleman and yeoman model of society has persisted. Maybe this model provides a kind of social balance: some people work and others shine and talk.

The problem of national character is still a matter of dispute—some people recognize it, while others consider it a fiction. It seems that geographical conditions, climate, social and economic arrangements, etc., cause certain personality traits to be more favorable in a given environment from the point of view of adaptation to that environment. People endowed with these traits are more likely to procreate than people lacking these traits, so with time the genotype (genetic pool) polarizes towards these traits. Theoretically, we can assume the existence of a national character, even one based on a specific genotype. How it really is, we do not know; some nations, such as the Jewish, show very durable traits of character that last for centuries, but on the other hand these traits fluctuate more markedly depending on whether the people supposedly endowed with this national character live in the diaspora or in their free state. To a certain extent, the “national” characteristics of the Poles change similarly depending on whether they live among their own people or among strangers. It is not uncommon that Poles, unbearable and unproductive among their own people, become disciplined and creative among strangers, so that one sometimes comes to the sad conclusion that they should rather live in the diaspora.

These remarks are very hypothetical; as yet, the lack of adequate scientific observation does not make it possible to speak authoritatively about national character. Nevertheless, the psychiatrist must be aware of the human environment in which he works, because depending on that environment, various problems—including personality traits—come to the fore.

In Poland, psychiatrists usually deal with psychasthenics and hysterics, because these two types of personality are certainly predominant in our country. Despite the extreme differences between the two types of personality, there is a fundamental similarity between them. Both hysterics and psychasthenics seek affirmation of their surroundings and both have problems with their own self-portrait (“how I am”). Both problems indicate a degree of emotional immaturity. Emotional maturity, if it exists, is expressed, among other things, in a certain independence from the environment—a mature person does not have to keep looking for support in the environment, he has his own opinion, and also in the ability to look at himself as objectively and critically as possible—a mature person does not have to keep looking for self-affirmation in the environment.

Due to the aforementioned fundamental similarities between hysterical and psychasthenic characters, psychotherapeutic approaches to people in both personality circles have many things in common. Both require affirmation. They need to feel support in the doctor. Sometimes he is the only person who understands them and does not reject them. The second problem is self-portrayal; both need to be taught the ability to look at themselves more objectively. The hysteric tends to overlook his faults, and the psychasthenic tends to exaggerate them.

The ability to look at oneself objectively is one of the most difficult human skills, requiring great maturity and life experience. A person gifted with such a skill frees himself to a great extent from the pressure of the social mirror, and becomes more independent and courageous in his judgments and modes of behavior. This is an important step in the attainment of human freedom. The striving for freedom is a great strength of man; and it has already been mentioned how this strength, uncharged, may be unleashed in a psychotic form. Schizophrenia is the pathological acquisition of freedom at the expense of reality and eventually enslaves one no longer in the real world, but in the psychotic world created by projecting what is most personal and intimate into the surrounding world.

A psychiatrist who tries to teach his patient to see himself objectively protects him from a pathological distortion of reality. He also strengthens his hierarchy of values, thanks to which the decision-making process runs more smoothly in such a person. For the hysteric, it is important to expand and deepen consciousness; he must reduce the burden of processes occurring below the threshold of consciousness. For psychasthenics, on the other hand, it is important to reduce the ballast of potential functional structures and increase the number of realized functional structures. The psychasthenic who gains self-confidence decides more easily to realize his potential structures, the probability factor of realization of the functional structures increases, thus he stands on more real ground.

The psychasthenic’s consciousness is usually overloaded with potential activity structures, and it should be relieved a little, especially because what is in the psychasthenic’s consciousness is usually unpleasant for him and associated with a negative self-image. When the psychasthenic manages to increase the number of functional structures realized, the burden of his consciousness decreases, he gains more self-confidence, and the decision-making process becomes easier. For this to happen, the psychasthenic must believe in the approval of the surroundings, that what he realizes will not be rejected, condemned, laughed at, etc.

In the psychasthenic, realized structures are often guilt-ridden—this is also true of potential structures, but to a lesser degree than realized structures; the approval of the environment reduces guilt and thus lessens the burden of consciousness. For the hysteric, the problem is different; his consciousness is relatively shallow and he realizes his potential functional structures too easily. One should strive to expand the field of consciousness and deepen it. As a result, the realization of potential functional structures will not proceed so smoothly. The hysteric will begin to feel the boundary between his dream and reality. His image of the surrounding world and of himself will be less hypocritical.

This is perhaps the most critical point in the psychotherapy of hysterics. The hysteric is afraid of the truth and sometimes desperately defends himself against it. In order for him to see this truth (expansion of the field of consciousness), he must have a sense of strong support in his environment (i.e., in the person of the therapist). Man seeks the support of his fellow human beings primarily in those situations in which he himself feels insecure. This is probably why his beliefs regarding metaphysical matters (religious), norms governing relations between people (moral, political), etc. are mostly group-based. The conviction that I am not the only one who feels this way about unclear and doubtful matters undoubtedly adds strength to this conviction.

Neither hysterics nor psychasthenics are certain of their position. However, this uncertainty has different causes in one and the other. In psychasthenics, the uncertainty stems from the difficulty of the decision. Of course, this is a circular causal connection, for the difficulty of the decision is in turn a consequence of the uncertainty. However, unable to realize his potential functional structures, the psychasthenic is still as if suspended in a vacuum, unable to check himself. That is why he needs the support of his environment so much. The hysteric, on the other hand, achieves apparent self-confidence through ease of realization of potential functional structures, but deep down he does not feel sure of himself, and so he frantically seeks approval from his environment. This is why he frantically seeks the approval of his surroundings. He does not find it, however, because his image of the surrounding world and of himself is not consistent with the opinion of his surroundings.

There is a certain analogy here between the attitude of the paranoid and the hysteric. The truth of the paranoid is also incompatible with the truth of the surroundings and the paranoid persistently fights for it, sometimes defending it against the whole environment, wanting to convince the environment of his rightness. The hysteric also wants to win the approval of the environment for his truth, he feels wronged when he cannot obtain it. The difference is that the truth of the hysteric is not so different from the truth of the environment as is the truth of the paranoid. The hysteric has a better chance than the paranoid of convincing his environment that he is right. But perhaps this is why it is sometimes more difficult to straighten out the distorted image of the world and one’s own person in the hysteric than in the paranoid. Many times the paranoid is quicker to believe that he is not persecuted by various cliques than the hysteric is to believe that he is not the most wronged of all, the most overworked, the most ill, etc. The paranoid’s confidence in his own truth is generally greater than the hysteric’s, and therefore the hysteric usually fights more violently for it than the paranoid. This is because one usually fights most fiercely for what one is not absolutely certain about.

It may be worth mentioning here sociological observations made on members of a sect believing in the imminent end of the world. Until the day of the alleged end of the world they kept their truth secret, did not look for new followers, considered themselves the chosen ones, who—the only ones of all mankind—will avoid destruction. When on the appointed day the end of the world did not come, they did not lose faith in the rightness of their truth, but from that time on they began to advertise zealously and to seek new followers.

The paranoid is convinced of his truth and generally does not have to fight as hard for it as the hysteric. The hysteric is not sure of it and therefore keeps looking for new “followers.” Perhaps that is why, among other things, he realizes his potential activity structures so easily, because he wants to prove himself right by doing so. The hysterical theater is partly evidence in the hysteric’s trial for his truth. It is known from psychiatric practice that both the symptoms of hysterical conversion and the traits of the hysterical personality intensify when the environment does not accept the hysteric, when it rejects him from himself.

A clear distinction should be made here between acceptance of conversion symptoms or personality traits and acceptance of the hysterical person. The acceptance of a symptom or personality trait strengthens the given symptom or trait according to the general principle that each acceptance by the environment of a realized functional structure strengthens its further realization. On the other hand, the acceptance of the hysterical person, despite his hysterical traits and symptoms, weakens these traits and symptoms, because the hysteric, feeling that he is approved, no longer has to fight so hard for the approval of the environment. This difference is often forgotten in the approach to hysterics; by condemning their personality traits and conversion symptoms, one condemns them, and conversely, by approving them, one sometimes approves of their personality traits and their symptoms.

Of course, we always try to look at the human being as a whole, but in this case it is necessary to make a kind of dissociation, to separate the whole person from his conversion symptoms and his hysterical personality traits. The difference between the approach to psychasthenics and the approach to hysterics should be emphasized here. The psychasthenic requires approval not only of his person as such, but also of his realized as well as potential functional structures, since approval of a functional structure reinforces its realization. In the hysteric, on the other hand, there is no need to strengthen realization and so in many cases it proceeds too easily; therefore disapproval of his certain functional structures may be beneficial. Thus, for the psychasthenic, we seek to increase the likelihood ratio of the realization of potential functional structures, and for the hysteric, to decrease it. Speaking in Pavlovian terms, one can express that in the psychasthenic we strive to strengthen arousal processes, and in the hysteric we strive to strengthen inhibition processes; formulating this in psychoanalytic terminology, one can say that in the psychasthenic we strive to strengthen id processes, and in the hysteric we strive to strengthen superego processes.

In psychasthenics we generally do not observe any falsification of the image of reality, either of one’s own or of one’s surroundings, at least not to the same extent as in hysterics. Some falsification probably exists in every human being and it results from the inborn defect of human nature. In the case of psychasthenics, the falsification of reality comes mainly from a dark self-portrait, from underestimation of one’s own strengths and abilities, from fear of realizing potential functional structures. Both hysterics and psychasthenics need support from other people in seeing themselves and their environment; they themselves feel as if they are too weak to see the world and themselves through their own eyes.

The hierarchy of values plays a fundamental role not only in choosing what is to be thrown out into the surrounding world, but also what is to be accepted from the surrounding world. In a word, it controls a two-way (outward and inward) stream of information. Already at the periphery of the reflex hatch, in the receptors themselves, selection takes place; some information is rejected as unnecessary for the system. So already at this lowest level of integration of the nervous system’s activities, the system of values operates; unfortunately, we do not know what it is about, because our consciousness does not reach that far, it includes only the highest levels of integration. And it is difficult for us to imagine a value system that is not in the field of consciousness.

So if the hysteric sees himself and the world around him differently from us, and if we cannot in any way convince him of the falsity of his view, it should not irritate us, because he himself is not aware of this falsification, it is taking place below the threshold of his consciousness. And we can only help him by expanding his field of consciousness. In a rather violent way this can be done in a hypnotic trance, and in a more gentle but more lasting way—in conversations with the sick person, during which he feels understood and accepted. To the hysteric, therefore, the Delphic gnothi seauton (“know yourself”) is very helpful, but it must be a true knowledge of oneself, reaching deeper than the shallow consciousness of the hysteric.

It should be remembered that in every human being there is a greater or lesser discrepancy between the conscious and subconscious hierarchy of values, as has already been mentioned. The conscious is generally more attuned to the demands of the surrounding world, and the subconscious—to one’s own needs and goals, of which a person is not always aware, rather more often than not he himself does not know what he most desires and what he most needs. This ignorance is the main reason that he is an enigma to himself. In this sense, every human being is a bit hypocritical internally, but this hypocrisy reaches its peak in hysteria. And this is due to the fact that the consciousness of the hysterics is extremely shallow and undiluted. Therefore, therapy for hysterics should aim to expand and deepen it.

In psychasthenia, the consciousness is much deeper and broader than in hysteria, if only due to the fact that most of the functional structures are not realized and remain in the consciousness in a potential form. However, this lingering causes a kind of overload of consciousness, with too many contradictory threads (e.g. a high level of aspiration typical for psychasthenics, with a low level of belief in the possibility of realization), which has a negative effect on maintaining an objective view of the world and of oneself. Psychasthenics should also be taught the truth about themselves, “taught” in the psychotherapeutic sense, of course, i.e. the person must find this truth on their own, it cannot be given to them ready-made, because the truth given, and not independently discovered, has no value from a psychiatric point of view. This claim also applies to psychiatrists themselves: they must discover psychiatric truths for themselves, truths discovered by others always remain alien to them; therefore, psychiatry cannot be learned, it must be lived.

This “teaching” of truth, however, proceeds in the opposite direction in the psychasthenic than in the hysteric. In the case of the hysteric, the aim is to burden the consciousness by expanding and deepening it; in the case of the psychastic, the aim is to relieve it by realizing potential functional structures. The psychasthenic often seems to suffocate under the weight of contradictory and often unpleasant potential functional structures. When he realizes some of them, he feels freer.

One should not delude oneself with the hope that a psychasthenic or hysterical person can be completely changed, i.e., that under our influence they will lose their psychasthenic or hysterical personality traits. Many enthusiasts of psychotherapy believe that with the use of appropriate psychotherapeutic methods and techniques the structure of a person’s personality can be changed and even believe that this is the proper aim of psychotherapy. It seems that these psychotherapists, just like the psychasthenics, suffer from a considerably exaggerated level of aspiration, which may—just like the psychasthenics—be due to a backlog of potential functional structures. In psychiatry, the possibilities for realizing potential functional structures are small compared to other disciplines of clinical medicine, such as surgery. Of course, man changes during his life and his personality changes, but its basic structure tends to persist from childhood until death. Here we touch upon the extremely difficult question of the dialectical changeability and immutability of human nature. In any case, one should be very careful and critical in assessing one’s own possibilities of changing other people, because too much faith in such possibilities simply makes a psychotherapist ridiculous.

The term “psychasthenia” (and derivative words) is often, especially in the press, distorted (i.e., misspelled: psychostenia, psychoastenia, etc.); it is equivalent to the German term: Psychasthenie.

From Wiki: Years later, as Marshal of Poland, Piłsudski recalled that Dzerzhinsky "distinguished himself as a student with delicacy and modesty. He was rather tall, thin and demure, making the impression of an ascetic with the face of an icon... Tormented or not, this is an issue history will clarify; in any case this person did not know how to lie."

Very interesting article (and thanks for the shout out). This helps me crystallize in my mind a type of person with whom I am quite familiar, as there were many such people in and around the social justice co-op where I once lived.

They were usually the children of affluent parents, who were often ivy-league professors, architects, or similarly successful. The kids were brighter than the average person, though apparently less so than their parents. All the ones I knew were white and most were male. Several of them went into art school, despite lacking a passion for art. They seemed to have this intense fear of their own mediocrity, and I suspected then that art offered a level of subjectivity that made failure less apparent. They would gravitate to really nebulous, conceptual art that's difficult to objectively evaluate, and then they would eventually abandon this and change their major to Don't Be Racist—a discipline at which failure is basically impossible.

And yet—paradoxically—failure is also guaranteed for the adherent of a church which offers no salvation. It makes sense, then, that the white person who would persevere in such a hostile environment would have such entrenched self-loathing, autoflagellance becomes its own objective. He takes his badness as a given, so the ideology attracts him, resonates with him, and is reifying.

But then he drags his cohort down with him. He'll rigorously defend the most unreasonable demands from nonwhites, and champion the most anti-white positions, proud of his own contrition on behalf of his unwilling peers. He has found a way to vitality and purpose, at the expense of his own kind.