Pathocrats Want To Destroy You

Areas of contention and other issues covered in Chapter 5 of Mitchell's thesis

Chapter 5 of Dr. Mitchell’s thesis concerns a number of “points of contention and other issues.” I will only cover a handful of the issues as the rest are covered briefly in my previous articles.

On the Spectrum?

The first is whether or not “continuum models” of normal personality are useful in identifying dark personalities (DPs). These models consider all attributes to exist in the general population to greater or lesser degrees, like the “Big Five” personality traits. If DP existed on a continuum, everyone would place somewhere on the spectrum; some would have a very low DP score, some very high, and others in between.

The response from participants was mixed on this issue, with academics defending continuum models and practitioners holding more of a categorical view of dark personality (i.e. you’re a predator, or you’re not). In their expert opinion, DPs “have a discrete set of specific attributes,” and continuum models aren’t specific enough to capture these attributes and subtleties (especially in the use of tactics); nor do they capture the degree of malevolence, which is usually unimaginable to most people.

To be fair to the academics, the current state of research at least partially justifies their position. However, I believe this to be mostly a result of the quality of their models, as well as their lack of hands-on experience with their subjects (on average). It’s much easier to believe in a categorical model when you experience DP/PPPs up close. The fact that the vast majority of people aren’t even aware of such people’s existence and can’t comprehend it even when first exposed to it suggests to me that the difference here is quite vast.

For all intents and purposes, DP is a collection of attributes and tactics that show up together. I think it’s unlikely that there is an equal number of people who fake emotions but who are not at all malevolent, for example; or callous sadists who take full responsibility for their harmful actions. It doesn’t seem like these attributes vary independently from each other. In other words, you either learn how to fake emotions and create fake personas in order to con other people into thinking you’re just like them, or you don’t. And if you do, then chances you’ll have all the other PPP attributes.

So regardless of the academic debate, I don’t see a problem with thinking in categorical terms—which is how we directly experience such people anyway. It also helps not to vilify otherwise ordinary people. If someone does something we might consider callous, for example, it’s probably incorrect to call them a PPP if they don’t display any of the other attributes or tactics.

Impact

Next is the issue of impact on others. As a reminder, “dangerous and harmful” were the most frequent descriptors from participants, and they described a range of such harm, both physical and nonphysical, seemingly for the goal of destroying the target.

The data discuss forms of destruction including murder, emotional and mental ‘torture’ leading to suicide, diseases that may result from stress such as cancer, and addiction-related deaths resulting from ‘masking’ behaviours.

Some of the ways that these outcomes manifest in the behaviours of targets/victims include ‘aggression,’ ‘substance use to cope,’ ‘self-harm to cope,’ ‘trauma responses,’ ‘eating disorders,’ ‘constant flight fight freeze reactions,’ ‘overreactive,’ and ‘provoke self-harm.’

Contrary to the image of the violent psychopath, most of the harm described was emotional and psychological, e.g., diminishing and belittling, degrading, isolating, verbally insulting, gaslighting (“doing and saying things that make the target/victim question their own sanity and reality”), humiliating in public, provoking in public or private, eroding the target’s confidence and self-worth, disempowering, setting the target up for failure.

“I remember sitting with one of my peers in front of him [the person of DP] in one of these meetings where he had unleashed on my colleague, my stomach was churning, my mouth was dry. I could not even comprehend; it was disbelief at what was going on. I could feel my sphincter uncontrollably constricting. I have never experienced that in my life. I do not know how your body does that. It is almost like your brain shuts down. … at the absolute time of impact you cannot even speak.” (Category 4ii;1 note: This participant usually had staff of around 20,000 to 30,000 people. It took this person, in their estimation, around 7 years to return to their usual level of capability and confidence following several years of working for this person of DP)

Lobaczewski also describes the visceral response to one’s first encounter with psychopathy. First, he describes first arrest and torture at the hands of the security services:

When I was arrested for the first time on May 1, 1951, violence, arrogance, and psychopathic methods of forced confession deprived me almost entirely of my capacity for self-defense. My brain stopped functioning after only a few days’ detention without water, to such a point that I couldn’t even properly remember the incident which resulted in my sudden arrest. I was not even aware that it had been purposely provoked and that conditions permitting self-defense did in fact exist. They did almost anything they wanted to me. I only managed to gather enough strength to refuse to sign the completely fabricated reports.

He describes the situation of a pathocracy more generally as follows:

When the human mind comes into contact with this new reality so different from any experiences encountered by a person raised in a society dominated by normal people, it releases psychophysiological shock symptoms in the human brain with … The mind then works more slowly and less keenly … Especially when a person has direct contact with psychopathic representatives of the new rule, who use their special knowledge and experience so as to exploit the traumatizing effect of their personalities on the minds of the “others,” his mind succumbs to a state of short-term catatonia. Their humiliating and arrogant techniques, brutal paramoralizations, and so forth deaden his thought processes and capacity for self-defense, and their divergent experiential method anchors in his mind. …

Only once these unbelievably unpleasant psychological states have passed, thanks to rest in benevolent company, is it possible to reflect—always a difficult and painful process—or to become aware that one’s mind and common sense have been fooled by something which cannot fit into the normal human imagination. Man and society stand at the beginning of a long road of unknown experiences which, after much trial and error, finally leads to a certain hermetic knowledge of what the qualities of the phenomenon are and how best to build up psychological resistance thereto. This makes it possible to adapt to life in this different world and thus arrange more tolerable living conditions … We shall then be able to observe new psychological phenomena: knowledge, immunization, and adaptation such as could not have been predicted before and which cannot be understood in the world remaining under the rule of normal man’s systems.

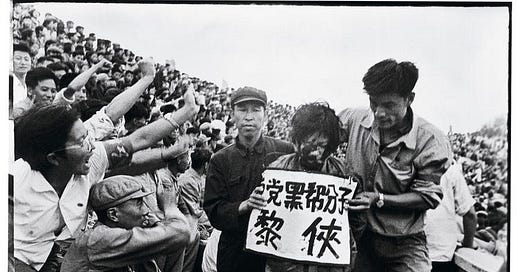

Take a look at that list of psychological harms again. This is what pathocrats do to their normal citizens: they degrade and belittle them, isolate them from each other, gaslight them daily, stage public humiliation rituals, provoke them, destroy their self-worth and confidence, completely disempower them politically, and set them up for failure. If your government is engaging in any of these behaviors, whether directly or through proxies, you can be sure that political psychopathy is at work.

Mitchell includes extensive examples of words used under various categories of harm. I’ve chosen a selection with a view to making the connection to political psychopathy and pathocracy.

If you appreciate ponerological perspectives, apprehending the propensities of perverse predators, and pondering pathological political processes, please consider subscribing or upgrading your existing subscription:

Paid subscribers get access to our twice-a-month Zoom meetups where we discuss reader questions, go more in-depth into the content I publish, and debate issues raised by participants. We recently discussed the relation of ponerology to the Covid response and heard differing views on the Great Barrington Declaration, for example. The next meeting is scheduled for December 7.

Mental

According to Lobaczewski, “neurosis” and trauma is human nature’s response to subordination to pathological people. In a pathocracy, everyone is affected to some degree:

In a pathocratic state, every person with a normal nature thus exhibits a certain chronic neurotic state, kept under control thanks to the arduous efforts of reason.

We don’t use the word anymore, but it encompasses various mood disorders such as anxiety and depression. Among the responses Mitchell quotes from her participants we find the following:

PTSD, anxiety disorder, stress, low mood, mental health problems, trauma responses, brain damage

hypervigilance, always scanning for threats, hyperarousal, walking on eggshells

chronic self-doubt, difficulty making decisions, loss of self-respect, feeling of not being believed

‘victims don’t seem to be able to employ the usual mechanism of “this person has treated me badly, so I will just forget about him/her and move on” because processes are dragged out’

As a nation becomes pathocratic (whether gradually or suddenly), one would expect to see increasing rates of these disorders in the general population.

Emotional

Abhorrence and fear, among other emotions, are also normal human reactions to predatory pathology. Mitchell quotes these feelings:

constant state of fear, distress, shame, anger, degradation, despair, lack of trust, self-blame

‘feeling of can never escape,’ ‘will never be free,’ ‘no escape,’ ‘feel trapped and stuck,’ ‘immense overwhelm,’ ‘completely depleted’

emotional dysregulation, aversion to sexual contact, feeling like one is going crazy, frequent nightmares, loss of spirituality

These reactions are deliberately evoked by pathocrats. For those of you who have read my edition of Political Ponerology, you may recall this quote from a Stasi manual:

“To develop apathy ... to achieve a situation in which [the subject’s] conflicts ... are irresolvable ... to give rise to fears ... to develop/create disappointments ... to restrict his talents or capabilities ... to harness dissentions and contradictions around him for that purpose [reducing his capacity to act].”

Physical

Mitchell’s participants described several forms of physical abuse and outcomes, including:

torture (cutting off ears, pulling out eyes), murder, rape (sodomy, rectal prolapse), harm to the target’s friends, pets, and property, neglect (e.g., of children), physical assault and threats

early death, health problems, suicide attempts and ideation, worn out immune system, physical exhaustion, sleep difficulties, headaches, high blood pressure, panic attacks, stress-related illnesses, fertility problems

Pathocrats love torture, and what they get up to is probably worse than you can imagine. Read

’s piece on Pitești if you want to get an idea. According to Lobaczewski, even the police themselves (those who weren’t psychopaths) were not immune from longterm mental and physical effects.Social, Relational, and Reputational

The first shock experienced by a people under pathocracy is a breakdown in social bonds and the isolation of each citizen even from those closest to them, accompanied by a pervasive sense of paranoia and mistrust. This is simply a macrosocial version of pathological dynamics we find at lower social scales. Mitchell finds the following descriptions:

isolation leading to despair, having no one to turn to for support, damaged and lost relationships, becoming an outcast, having friends and family turned against them, loss of capacity to trust

being seen as unstable, destruction of reputation, manipulation of teachers and school communities

Pathocrats create both widespread social and relational breakdown, as well as targeted campaigns against specific targets. Pathocrats invented cancel culture.

Financial

Whether for their own personal enrichment or simply the destruction of their target, DPs will drain your bank account.

financial exploitation, leaving a partner with debt, dragging the target to court repeatedly

poverty, financial problems, losing one’s home or car

Scaled up to the political level, pathocrats target the finances of their enemies.

Work-Related

The last category of harm relates to work. DPs will negatively affect your work relationships, get you fired, destroy your morale, wreck your career, and ruin your professional reputation.

Mitchell makes a couple additional points in this section. First, she quotes a participant:

“The victims are often the ones seen as crazy because they are frequently under attack regarding something very important to them like their children, their job, their freedom, their friends etc and in a way that takes a lot of energy to address and that others cannot see. In some cases, this has been going on relentlessly for years. The victim may seem unbalanced, over-reactive, aggressive, controlling. … They can find it hard to make decisions as the DP behaviours can lack transparency and the victim is left double guessing, is the DP behind this or is this just a random event?” (Category 4ii)

When the intelligence community targets an individual using psychopathic methods of intimidation, it’s no wonder others see them as “crazy” and “paranoid.”

Several research participants discussed the point that people who recognise the set of behaviours of people of DP and are driven by fairness often try to expose people of DP. This appeals to the predatory, ‘game-playing’ nature of people of DP … and so they often commence a process of destruction of the ‘exposer’ …

This, too, is scaled up in a pathocracy. Anyone who shows the ability to “diagnose the system” (like Lobaczewski and his colleagues), or expose the psychopath’s true nature, is seen as an existential threat and dealt with accordingly.

Next up: Impact on children, and other issues

Category 1 = personality researchers, Category 2 = behavioral researchers, Category 3 = expert forensic practitioners, Category 4i = non-forensic professional practitioners, Category 4ii = non-forensic corporate practitioners, Category 4iii = non-forensic community practitioners.

My father was a dark tetrad and I his prime target. Other DPs in my childhood--most of them charged with my care--also wreaked tremendous harm. Then some bosses, and, most recently, one of the doctors I turned to for help.

From an Interpersonal Neurobiology (IPNB) perspective, DPs exploit the nervous system's survival mechanisms, causing heightened fight-flight-freeze responses and chronic hyperarousal. Long-term exposure disrupts the autonomic nervous system, impairing self-regulation and resilience, which can lead to lasting PTSD.

Gaslighting undermines interoception (ability to connect to internal bodily states), creating confusion and self-doubt. It can impair the prefrontal cortex’s ability to make decisions, leading to a shutdown of higher cognitive functions under stress.

Emotional abuse disrupts the brain's limbic system, affecting emotional regulation, attachment, and trust. Isolation and social fragmentation deprive individuals of co-regulation through safe relationships, exacerbating dysregulation.

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, under constant activation, leads to immune suppression, inflammation, and stress-related illnesses (virtually all chronic conditions, mental health issues, and recurrent pain).

DPs' behaviors target key interpersonal neurobiological needs, such as connection and trust, breaking down social support systems and fostering alienation.

Chronic stress and fear from workplace abuse impair executive functioning, diminishing creativity and problem-solving abilities.

To counter this we need to implement psychoeducation to equip individuals and communities with knowledge about the neurobiology of trauma and the tactics of DPs to foster awareness and resilience.

Build community and create safe, connected spaces for co-regulation and healing to counteract isolation and mistrust.

Implement restorative practices that restore nervous system balance, such as mindfulness, physical activity, somatic therapies, and safe relationships.

Advocate for change and highlight the need to identify and prevent pathocratic dynamics in institutions and governance.

Offer validation and support, acknowledging victims’ experiences and offer practical tools to rebuild self-trust and counteract the neurobiological effects of abuse.

Domination hierarchies are a core issue. Dr. Robert Sapolsky’s research makes clear how hierarchy itself drives stress, inequality, and harm. Flattening these hierarchies isn’t just ideal; it’s essential for our survival as a species, fostering the connection and collaboration we desperately need.

#TraumaAwareAmerica

OMG. I got chills reading all of this. This is exactly what's happeing here in Peru. I knew politicians where cooking something. Now I'm sure about what are they doing and how far they might go to keep this hell on earth. I will spreading this work in spanish. People here need to know this