Psychopaths, Sociopaths and Antisocials

A ponerology glossary entry untangling conflicting definitions

This series expands on the glossary entries included in Political Ponerology.

psychopathy: Łobaczewski, following an older European convention, uses the term to refer to genetic personality disorders in general. In modern psychiatry and psychology, psychopathy refers to a specific personality disorder assessed by instruments such as Robert Hare’s PCL-R, Scott Lilienfeld et al.’s PPI-R, and others. Lobaczewski calls this disorder “essential psychopathy” to distinguish it from others (like schizoid or obsessive-compulsive personality disorders, for instance). The PCL–R scores individuals on 20 items, which fall under two factors and four facets. Factor 1 (interpersonal–affective): glibness/superficial charm, grandiose sense of self-worth, pathological lying, conning/manipulative, lack of remorse or guilt, shallow affect, callous/lack of empathy, failure to accept responsibility. Factor 2 (impulsive–antisocial): need for stimulation, parasitic lifestyle, no realistic long-term goals, impulsivity, irresponsibility, poor behavioral controls, early behavioral problems, revoke conditional release, criminal versatility. Factor 1 corresponds to the ICD-11 “dissociality” trait domain: “Disregard for the rights and feelings of others, encompassing both self-centeredness and lack of empathy.” Factor 2 corresponds to the ICD-11’s “disinhibition”: “A tendency to act rashly based on immediate external or internal stimuli (i.e., sensations, emotions, thoughts), without consideration of potential negative consequences.” In contrast to the PCL-R, David J. Cooke et al.’s CAPP explicitly assesses fearlessness and lack of trait anxiety, and does not directly measure criminal behaviors, only the personality deficits thought to lead to such behavior, thus potentially making it useful in assessing psychopathy in non-criminal community samples.

Kent Kiehl argues that psychopathy is characterized by abnormalities in the paralimbic system of the brain (a core part of the instinctive substratum containing the amygdala, hippocampus, anterior and posterior cingulate, orbital frontal cortex, insula, and temporal pole) that develop from birth. Thomson summarizes: “psychopathy is likely to be explained by a collective system of integrated brain regions that are implicated in the job of emotion regulation, social cognition, threat perception/recognition, attention, decision-making and affective processing.”

As Thomson argues, psychopathy is unlikely to have a single cause; rather it is likely to be more complex and multi-causal in nature, with biological, psychological, and social factors having contributive and interactive effects. While individuals without the genetic predisposition will not develop the full symptomology, specific social factors are likely to have at least an exacerbatory effect on its development, with others having a protective effect. For example, the following potential social risk factors for the development of psychopathic traits have been identified: cortisol and tobacco exposure in utero, lack of breastfeeding, omega-3 deficiency, and lead exposure. Factors contributing to Factor 2 antisocial behavioral features include low family socioeconomic status, poor parenting styles, and childhood abuse.

On the lack of identified genes for psychopathy, Essi Viding writes: “The way that genetic risk for psychopathy operates is likely to be probabilistic, rather than deterministic: genes do not directly code for psychopathy. But genes do code for proteins that influence characteristics such as neurocognitive vulnerabilities that may in turn increase the risk for developing psychopathy, particularly under certain environmental conditions. Psychopathy is not a single gene disorder, unlike, for example, Huntington’s.” Researchers believe psychopathic traits “are best explained by the combination of additive effects, rare alleles, gene–gene interactions, and gene-by-shared-environment interactions.” Based on behavioral genetics, including twin studies, heredity accounts for 40–60% of the variance of psychopathy, the rest by environment; molecular genetics can only account for 10–20% at this time. That said, the study of psychopathy’s molecular genetics is still in its infancy. One recent study accounted for 30–92% of symptom variance based on gene expression in five genes.

Psychopaths are often also diagnosed with one or more of the following DSM-5 personality disorders: antisocial, borderline, histrionic, narcissistic, and paranoid. While not identical to “antisocial personality disorder,” the two overlap. Many with antisocial personality disorder are better understood as “secondary” psychopaths, or what Łobaczewski calls frontal characteropaths (i.e., the etiology is largely environmental in nature). Closely related to Factor 1 and of importance for ponerology is the “dark personality” or “Dark Tetrad” model: narcissism, Machiavellianism, psychopathy, and sadism, the last three of which are highly correlated with low agreeableness and conscientiousness (i.e., dissociality and disinhibition), while narcissism is highly correlated with extraversion. Paulhaus and colleagues propose that all four dark traits may fall under the Honesty-Humility factor (i.e., deceitful, greedy, sly) of the HEXACO personality model (essentially a “Big Five Plus One” model.

The above is what I wrote (with slight changes here) for the glossary section included in the 2022 edition of Political Ponerology. Here I want to expand on the above to clear up some confusion about how professionals and the public use words like psychopathy, sociopathy, and antisocial personality disorder. It can be confusing, because even professionals (like clinicians and researchers) are not always precise about what terms they use, and what they mean by the terms they do use. This is even more confusing when taking into account how the general public uses such words. However, the situation is not hopeless.

So what is psychopathy? Many people seem to use the word simply as a pejorative or as a loose description for someone who is either violent, weird, or insane (or simply someone they don’t like). None of these are accurate. The word itself has actually been carefully defined since at least 1941, and increasingly so for the past 40-plus years. The phenomenon it attempts to describe had other names prior to settling on psychopathy, like “innate preternatural moral depravity” and “moral insanity.” In the early 1940s, several psychologists (most notably Hervey Cleckley) moved their focus away from directly observable antisocial and immoral behaviors to the actual core personality features underlying those behaviors. And since the 1980s, the standard measurement tool has been Robert Hare’s Psychopathy Checklist, which, as noted above, focuses on two factors with multiple items: affective/interpersonal traits, and impulsive/antisocial behaviors.

The use of the PCL-R for a diagnosis of psychopathy is most common in forensic situations (courts, prisons, and high-security psychiatric units) and academic research.1 But you won’t find the word in the DSM, the standard classification of mental disorders used by mental health professionals in the United States. Instead you will find “antisocial personality disorder.” In order to be diagnosed with ASPD, someone has to meet at least three of the following descriptors (in addition to being over the age of 18, having a history of conduct problems prior to the age of 15, and not being schizophrenic or bipolar):

Failure to conform to social norms and laws, indicated by repeatedly engaging in illegal activities.

Deceitfulness, indicated by continuously lying, using aliases, or conning others for personal gain and pleasure.

Exhibiting impulsivity or failing to plan ahead.

Irritability and aggressiveness, indicated by repeatedly getting into fights or physically assaulting others.

Reckless behaviors that disregard the safety of others.

Irresponsibility, indicated by repeatedly failing to consistently work or honor financial obligations.

Lack of remorse after hurting or mistreating another person.

The DSM may be the standard in the U.S., but it is not flawless. Aside from general criticisms of its entire approach to personality disorders,2 the criteria for antisocial personality disorder are particularly open to critique. As should be obvious from the list, a person with a history of crime, impulsivity, and irresponsibility can be classified as ASPD. That includes the vast majority of incarcerated criminals.

The problem is that this criminal population is heterogeneous. One can be diagnosed ASPD and yet very clearly not be a psychopath (as the term has been understood for the past 80 years or so). Here’s how Kent Kiehl summarizes the research:

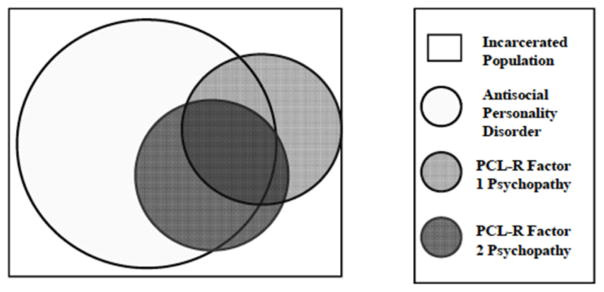

ASPD is present in 65%–85% of the incarcerated population while psychopathy is present in only 15%–25% of that population. Psychopathy is present in 20%–30% in those who have ASPD. Factor 1 (interpersonal-affective) traits are moderately correlated with ASPD (r = .40), while Factor 2 (behavorial-impulsivity) traits are strongly correlated with ASPD (r = .80).

And here’s a visual representation:

And here’s what he has to say about the ASPD vs. psychopathy debate:

… orthodox psychiatry’s approach to psychopathy continued to be bedeviled by the conflict between affective traits, which traditionally had been the focus of the German School, and the persistent violation of social norms, which became a more modern line of inquiry. Almost everyone recognized the importance of the affective traits in getting at psychopathy, but many had doubts about clinicians’ abilities to reliably detect criteria such as callousness. It was this tension—between those who did and did not think the affective traits could be reliably diagnosed—that drove the swinging pendulum of the DSM’s iterations. Another organic difficulty with the notion of including psychopathy in a diagnostic and treatment manual is that these manuals were never designed for forensic use. Yet it has always been clear that one of the essential dimensions of psychopathy is social deviance, often in a forensic context.

The DSM, first published in 1952, dealt with the problem under the category Sociopathic Personality Disturbance, and divided this category into three diagnoses: antisocial reaction, dissocial reaction, and sexual deviation. It generally retained both affective and behavioral criteria, though it separated them into the antisocial and dissocial diagnoses.3 In 1968, the DSM-II lumped the two diagnoses together into the single category of antisocial personality, retaining both affective and behavioral criteria. The German tradition was finally broken in 1980 with the publication of the DSM-III, which for the first time defined psychopathy as the persistent violation of social norms, and which dropped the affective traits altogether, though it retained the label antisocial personality disorder.

By dropping the affective traits dimension entirely, the DSM-III approach, and its 1987 revisions in DSM-III-R, ended up being both too broad and too narrow. It was too broad because by fixing on behavioral indicators rather than personality it encompassed individuals with completely different personalities, many of whom were not psychopaths. It was also too narrow because it soon became clear that the diagnostic artificiality of this norm-based version of ASPD was missing the core of psychopathy. This seismic definitional change was made in the face of strong criticism from clinicians and academics specializing in the study of psychopathy that, contrary to the framers of the DSM-III, had confidence in the ability of trained clinicians to reliably detect the affective traits. Widespread dissatisfaction with the DSM-III’s treatment of ASPD led the American Psychiatric Association to conduct field studies in an effort to improve the coverage of the traditional symptoms of psychopathy. The result was that the DSM-IV reintroduced some of the affective criteria the DSM-III left out, but in a compromise it provided virtually no guidance about how to integrate the two sets. As Robert Hare has put it, “An unfortunate consequence of the ambiguity inherent in DSM-IV is likely to be a court case in which one clinician says the defendant meets the DSM-IV definition of ASPD, another clinician says he does not, and both are right!”

The Hare instruments have proved to be extremely useful, and … they are the gold standard for the clinical diagnosis of psychopathy. They have been translated into a dozen languages, and are used around the world. Yet, as we have already mentioned, the orthodox view as expressed in the DSM-IV, and now the DSM-IV-TR, does not recognize psychopathy as a condition separate from ASPD. The debate remains robust, though, like many issues with psychopathy, is asymmetric. There are dozens of peer-reviewed papers published each year that validate the assessment of psychopathy using the Hare criteria, but very few arguing that ASPD is the better diagnostic tool. The roots of this continuing, if decelerating, debate lie not only in the historical skepticism of describing a condition in moral, seemingly judgmental, terms, and in continuing doubts about the reliability of detecting the affective traits, but also in the problem of diagnostic tautology. Academic psychiatry is justifiably troubled by diagnostic criteria that include too many behavioral components. It is theoretically unsettling to define a condition as a mental disorder just because it is has been declared to be antisocial by the legal system.

What about “sociopathy”? Here’s Kiehl again:

The term psychopathy comes from the German word psychopastiche, the first use of which is generally credited to the German psychiatrist J.L.A. Koch in 1888, and which literally means suffering soul. The term gained clinical traction through the first third of the 1900s, but for a time was replaced by sociopathy, which emerged in the 1930s. The two terms were often used interchangeably by clinicians and academics. Sociopathy was preferred by some because the lay public sometimes confused psychopathy with psychosis. Many professionals also preferred sociopathy because it evoked the notion that these antisocial behaviors were largely the product of environment, an opinion held by many at the time. In contrast, psychopathy evoked a deeper genetic, or at least developmental, cause. When the DSM-III introduced the broader diagnosis of ASPD in 1980, sociopathy and sociopath fell out of modern favor.

Summing up the confusion so far: ASPD is a catch-all diagnosis focused primarily on individuals demonstrating antisocial behaviors—which may (and do) have multiple etiologies. As a result of its proponents’ hesitancy over the ability of clinicians to diagnose affective traits, they eliminated them as criteria but sacrificed diagnostic precision in the process. ASPD therefore overlaps, but is not identical with, psychopathy. Psychopaths are usually also diagnosable as ASPD, but have a distinct personality structure characterized by “core psychopathic traits” that most ASPDs lack.4 Psychopaths are cold-blooded and calculating. Non-psychopathic ASPDs are hot-headed and emotional. Psychopaths tend to use primarily instrumental aggression. ASPDs use primarily reactive or hostile aggression.

Sociopathy, on the other hand, is the least well-defined (and least used) term, and the most likely to be used idiosyncratically. Some simply prefer the way it sounds—it’s less “stigmatizing.” Lykken, by contrast, used it to distinguish “the larger fraction [of the population] who have grown up unsocialized primarily because of environmental rather than genetic reasons.” More broadly, he classified ASPD “as a family of disorders comprising psychopaths and sociopaths.” Lobaczewski used the term similarly, as a way not of implying that the psychopathic personality was in fact caused solely by social forces (as many professionals did in the middle of last century), but of differentiating environmental sociopathy from heritable psychopathy.5

In fact, Lobaczewski was critical of catch-all definitions like ASPD that could apply to multiple types with different etiologies. Describing the state of affairs in Poland when he was working, he wrote:

The essence of psychopathy may not, of course, be researched or elucidated. Sufficient darkness is cast upon this matter by means of an intentionally devised definition of psychopathy which includes various kinds of character disorders, together with those caused by completely different and known causes. (PP, p. 278)

With all that said, here are the most commonly used terms, how they correspond with Lobaczewski’s terms, and how they differ:

psychopathy : essential psychopathy (Lob.) : trait dissociality (ICD) : primary psychopathy — highly heritable, characteristic interpersonal/affective traits, antisocial behaviors

sociopathy : sociopathy/functional characteropathy (Lob.) : secondary psychopathy — lower heritability than psychopathy, social risk factors (e.g. childhood abuse, poor parenting, low SES), antisocial behaviors

[not commonly used North American term] : frontal characteropathy (Lob.) : organic pseudopsychopathy or secondary personality change (ICD) : secondary psychopathy — primarily the result of traumatic brain injury; dysfunction in cognition, affect, and behavior sharing features with the above

antisocial personality disorder overlaps with all of the above (most strongly with sociopathy)

Note that some uses of the terms above imply a cause of one sort or another, while others are neutral. Sociopathy tends to imply environmental factors. Psychopath (especially as used by Lobaczewski) implies strong heredity and lack of response to treatment. Characteropathy (or pseudopsychopahy) is explicitly tied to brain injuries. ASPD is neutral as to cause.

Incidentally, there’s no good evidence that psychopaths are overrepresented among murderers. As Thomson wrote in Understanding Psychopathy (p. 40): “overall the research suggests adults who are convicted of homicides are not more likely to be psychopathic. However, homicides by psychopaths are more often premeditated and goal-directed … In adult prisoners, there is evidence to suggests murderers … actually show lower levels of psychopathy.”

So, when I use the word psychopath here, I am using it in the sense it has developed over the past 80 years, primarily by Cleckley and Hare, and as currently defined by the PCL-R, which is the diagnostic and research standard.6 I rarely use the term “antisocial personality,” since I find to overly broad and almost worthless in terms of precision. When I use sociopathy, it will be along the lines of Lykken and Lobaczewski’s use of the term.

See the extensive literature collected on Hare’s website. A search on Google Scholar returns the following numbers of hits for search terms: “sociopathy” (20,500), “antisocial personality disorder” (92,500), “psychopathy” (139,000).

Many researchers think that the current personality disorders are a mess and do not actually capture distinct disorders. This is a complex issue, but one of their problems is that of comorbidity. If you can be diagnosed with one PD, chances are you will also be diagnosed with another, or several. Because of this, some critics propose revising the DSM to be more in line with the WHO’s ICD, which avoids this problem and is arguably cleaner in terms of theory and practice.

The ICD’s current equivalent to the DSM’s ASPD is “dissocial personality,” which is closer to psychopathy than ASPD in its criteria by virtue of it retaining the affective traits. Even then, however, it doesn’t fully capture psychopathy.

See also this paper: “Psychopathy is linked to biological processes in the brain, and is a highly heritable disorder. … Features and behaviors, such as lack of empathy, remorse, and guilt as well as manipulativeness, callousness, and grandiosity comprise the core psychopathic traits. Antisocial conduct is often comorbid with these core traits, which together are referred as to psychopathy. … the evidence suggests that ASPD and psychopathy stem from divergent biological processes.”

To add further confusion, some researchers, starting with Karpman in the 1940s, use “primary psychopathy” and “secondary psychopathy” to distinguish these two types. And the ICD-10 used the term “organic pseudopsychopathic personality” to describe brain-damage-induced personality changes.

But that’s not to say “the science is settled.” There are still open questions about the nature of psychopathy and its expression, leading to qualifiers like “successful” and “subclinical” psychopathy. In other words, what should we call individuals who seem to have core psychopathic traits, but don’t demonstrate as obvious antisocial behaviors? The current ICD attempts to solve this problem by using a dimensional approach. For example, a “successful psychopath” might be diagnosed as having moderate personality disorder with dissocial traits, and a “full-blown psychopath” has dissocial and disinhibited (corresponding to PCL-R factors 1 and 2).

I agree with you. The trend now is to lump every disorder together.

As I remember it sociopaths are basically emotionless, but aren't necessarily prone to criminal or violent behavior. It's just that they don't show any empathy, and simply do what they want quite literally.

Psychopaths were similarly lacking emotion, but were much more prone to violence, and criminal activity.

The Autism Spectrum, now encompasses damn near everything now. It's really rather meaningless.

I don't understand the reason for lumping everything together, unless there's some underlying legal ramifications at play. Redefining the terms will result in different legal outcomes.

Also, it might result in more people being diagnosed with mental disorders that result in the loss of rights and freedom. I would imagine that is driving the push to put everything together.

Note: I will murder anyone who disagrees with my opinion. It's nothing personal though. (sarc...) 😉👉

Philanthropath is a socio/psychopath masquerading as a philanthropist. (coined by a substacker Margaret Anna Alice.) Thought you may enjoy that term. BG is a perfect example.