For previous installments of this series, see Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, and Part 4.

In Part 1 of this series, I covered the first 4 chapters of Mattias Desmet’s The Psychology of Totalitarianism (PT) in brief. Parts 2 through 4 each dealt with a chapter from part 2 of the book, in slightly more detail, as this is where the meat of totalitarianism is discussed. In this penultimate installment, I will cover the remainder of Chapter 8, which deals with some specific solutions, as well as the final three chapters, which comprise part 3 of the book, “Beyond the Mechanistic Worldview.” (In the next and final installment I will deal with the book in general terms and focus on what I perceive to be the book’s deficiencies.)

Given the theory Desmet presents over the course part 2, what kinds of things can be put into practice to combat mass formation and its mass effect, totalitarianism? Desmet rules out the first option—“violent elimination of an evil elite”—for a very simple reason: “they are utterly replaceable” (PT, p. 139). Leaders in particular will simply be replaced, but the system will remain stable. Additionally,

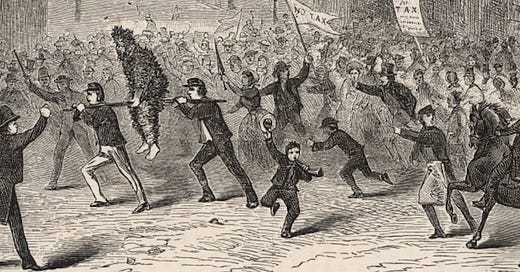

When the opposition uses violence, the crowd merely sees justification and a “get-out-of-jail-free” card to unleash its already enormous potential of frustration and aggression and take it out on those it views as the enemy … (PT, p. 140)

Violent rebellions get put down violently (and historically, the only successful rebellions are those with the backing of some disaffected segment of the very ruling elites in question). This leaves internal violence “generally counterproductive” (though he admits that externally sourced violence, e.g. invasion, can be effective). And leaves nonviolent resistance as the best method available (a point on which he agrees with Arendt).

Lobaczewski has some similar things to say regarding violence and leaders in Political Ponerology (PP), but for a slightly different reasons. He agrees that such methods are ineffective:

This phenomenon and its brutality are actually maintained—and the secret network of its heirs strengthened—by the threat of legal retaliation or, even worse, of retribution on the part of the enraged masses. Dreams of revenge distract a society’s attention from understanding the biopsychological essence of the phenomenon and stimulate the moralizing interpretations whose results we are already familiar with. … These problems, however, both present and future, can be solved if we approach them with an understanding of their naturalistic essence and a comprehension of the nature of those people who commit substantial evil. Such a solution would yield the full harvest of the years of our suffering. (PP, p. 314)

Such moralizing retribution, for Lobaczewski, only risks prolonging pathocracy where it exists, or reversion to conditions conducive to pathocracy and creation of a new cycle of ponerogenesis (remember, one form of evil, even if it’s in the guise of good, opens the door to another). It is an outdated weapon that, when effective (e.g. in the example of warfare), is only so in a manner similar to that in which amputating a leg in response to an ingrown toenail is effective: sure, it solves the problem, but at a high cost.

On the subject of leaders, Lobaczewski writes:

An observer watching such an association’s activities and organization from the outside and using natural or sociological concepts will always tend to overestimate the role of the leader and his allegedly autocratic function. The spellbinders and the propaganda apparatus are mobilized to maintain this erroneous outside opinion. The leader, however, is dependent upon the interests of the association, especially the elite initiates, to an extent greater than he himself knows. He wages a constant position-jockeying battle; he is an actor subject to control and direction. In macrosocial associations, this position is generally occupied by a more representative individual not deprived of certain critical faculties; initiating him into all those plans and criminal calculations would be counterproductive. In conjunction with part of the elite, a group of psychopathic individuals hiding behind the scenes steers the leader, the way Bormann and his clique steered Hitler, or Beria and his men with Stalin. If the leader does not fulfill his assigned role, he generally knows that the clique representing the elite of the association is in a position to kill or otherwise remove him. (PP, pp. 156-157)

So Lobaczewski would only partially agree with Arendt, for whom the totalitarian leader is “nothing more nor less than the functionary of the masses he leads” (PT, p. 139). To reiterate my point from the last installment, totalitarian leadership is not a monolith, and not all of its members are the self-hypnotized fanatics Desmet believes them to be. The early leaders and spellbinders, perhaps, but not so much the “secret society” leadership structure that develops with time, which is more Machiavellian and psychopathic.

The particular nonviolent means Desmet highlights is speech. While audible dissent may not be able to dehypnotize a fanatic, “it does reduce the depth of the hypnosis and prevent the masses from committing atrocities,” and “leaders prove sensitive to dissident voices” (PT, p. 141). It’s much easier to demonize and destroy opposition if they don’t have a voice—if the dominant hypnotic voice becomes absolute. Seeing and hearing them speak humanizes them to a degree. Desmet recommends sincere, calm, and respectful speech, both to mitigate the extreme reactions of the crowd, and to have an effect on the middle group—those “compliant but not hypnotized” (PT, p. 141)—who may be receptive to a rational analysis and refutation of the propaganda.

But he stresses that the intent should not be to convince those already hypnotized. You shouldn’t want to return things to the way they were before, because those were the conditions that gave rise to mass formation in the first place. And that’s precisely what the hypnotized do not want. Thus, such a maneuver will only make them more resistant. Rather, counterarguments should be presented in the context of “working groups, specialized in certain themes and topics”—to reestablish social bonds and structure. Desmet calls this a “countergroup” and offers “a more strategic option”:

… replacing one object of anxiety with another. … one could try to circulate an alternative narrative that puts the totalitarian regime itself forward as an object of anxiety … If such a strategy is applied moderately, this amounts to a warning for a real danger with good reason. (PT, p. 143)

However, as he notes, this deliberate instillment of anxiety crosses ethical bounds and can also drift into the same mass-formation dehumanization process.

Lobaczewski’s recommendations also include rational argumentation (see his discussion of how to approach ideology in PP, pp. 319-323) and creation of a countergroup (to be discussed in the next post), but only within a broader program of accurate psychological/ponerological education. He calls it “world therapy.”

The “new weapon” suggested herein kills no one; it is nevertheless capable of stifling the process of the genesis of evil within a person and activating his own curative powers. If societies are furnished an understanding of the pathological nature of evil—something they were unaware of before—they will be able to effect concerted action based on moral and naturalistic criteria. (PP, p. 326)

Chapter 9 begins Desmet’s presentation of a worldview he believes provides an alternative to the totalitarianism-forming mechanistic ideology, one strongly influenced by scientific giants like Einstein, Heisenberg, Schrödinger, Planck, Bohr, and Pauli, among others. He cites the implications of chaos theory and dynamic systems theory, which suggest fundamental ontological qualities of creativity and life, and reveal patterns behind otherwise “chaotic” dynamics (like the Lorenz attractor—an elegant pattern behind chaotic motion that only reveals its form when graphed in phase space). Like the chaotic movement producing the Lorenz attractor:

… life follows certain principles and sublime phenomena are hidden beneath its seemingly chaotic surface. And this is perhaps a person’s greatest task: to discover the timeless principles of life, in and through all the complexity of existence. (PT, p. 157)

It’s the development of these principles—and sticking to them, even if doing so results in short-term detriment—that leads to a sense and meaning of existence, purposefulness and aesthetics, and individual and collective strength. For Desmet these principles include: freedom of speech, self-determination, freedom of religion and belief. If a society loses touch with them, “it will decay into chaos and absurdity” (PT, p. 157), a society ruled not of law and principle, but based on the analysis of “experts” (PT, p. 158).

Chapter 10 undermines the strictly bottom-up view of causation (physics>chemistry>biology>psychology, etc.), favoring instead a circular causality of mutual influence (PT, p. 163) which sees the psychological realm as irreducible to biochemistry and physics. He cites the example of extreme cases of individuals with as little as 5% of their brains—their brain cavities almost completely filled with fluid—but who function as if they were fully brained and may have IQs of 130 or higher.

In principe, these observations do not exclude a biological determinacy of consciousness. They only show that such a determinacy, if it does exist, has to be extremely complex in nature, and that the brain—to speak in terms of complex and dynamic systems—at least possesses the property of self-organization and self-reorganization. … The causal relationship between consciousness and brain is not a one-way relationship. (PT, pp. 165-166)

He cites evidence from psycho-neuroimmunology and the phenomenon of psychogenic death. Curses do work. The only catch: everyone in your community has to believe they do. Patients can undergo complex operations under hypnosis, with no anesthesia. The placebo and nocebo effects are still not understood (just taken as a given in research studies), and may even be vastly understated.

In fact, the very existence of nocebo effects is an argument against mandatory medical interventions. Forcing people to get treatments they fear can be counterproductive. Just ask the victims of psychogenic death curses.

On closer inspection, the mechanism of psychogenic death, hypnotic sedation, and placebos is the same every time: An authority figure evokes a powerful mental image in the individual who is being addressed. This mental image can be positive … or negative …, but it has to be vividly and clearly present in the experience and it has to draw the attention away from all other mental activity. … When society as a whole is in the grip of anxiety and the accompanying images of illness and death, those images in themselves become a causal factor. (PT, pp. 169-170)

Finally, Desmet begins Chapter 11 with the observation that even in regimes that can’t yet be called totalitarian per se, “There is an ever-present, totalitarian undercurrent that consists of a fanatical attempt to steer and control life in far-reaching ways on the basis of technical, scientific knowledge.”

With every “object of anxiety” that has emerged in our society in recent decades—terrorism, the climate problem, the coronavirus—this process has leapt forward. The threat of terrorism induces the necessity of a surveillance apparatus, and our privacy is now seen as an irresponsible luxury; to control climate problems, we need to move to lab-printed meat, electric cars, and an online society; to protect ourselves against COVID-19, we have to replace our natural immunity with mRNA vaccine-induced artificial immunity. (PT, p. 176)

While we live in the age of “science,” one of the biggest scientific truths is routinely ignored: “All things small and all things large are connected, everything is part of an overarching, complex, and dynamic system” (PT, p. 177). Even when it comes to a virus, we need to take into account the whole context (psychological, sociological, economic), and not reduce it to some mechanistic monomania. The end point of science is not certainty, but awareness of the limits of our own rationality, and comfort in uncertainty. And the very thing that eludes scientific understanding turns out to be the most important thing, the “essence of life” (PT, p. 178). It’s here that Desmet veers into some of the more mystical, almost panentheist, musings of guys like Planck, who posited a cosmic Mind as “the matrix of all matter.” Nice.

He returns to developmental psychology, likening the trajectory of science to the childhood development discussed in part 1: from the fanatic pursuit of logical-rational understanding (and attendant childhood narcissism, dependence, anxiety, and isolation), through the choice between continued narcissism and (pseudo)rationality or healthy individuality and creativity, with the ability to tolerate uncertainty. There is a capital-M Mystery wrapped up in this little bit:

The more man advances in this process [of finding space for oneself in the relationship with Others], the more energy and creative power he will have. The ultimate potential that can be realized on this path is unclear, but the enormous influence of the psychological realm on the body … shows that its possibilities are extraordinary. (PT, p. 182)1

Science is faced with the same choice as the developing child: “we can shy away from anxiety and deny our uncertainty, or we can defy our narcissistic anxiety and accept the uncertainty” (p. 182). Desmet closes the chapter with a section on truth. He writes: “The real volte-face and revolution that society has to face is to shake off rhetoric and resolutely turn to truth as a guiding principle” (p. 187).

And that concludes my summary of the book. Please note that it can’t be considered a full summary. These are only the bits that caught my attention for one reason or another. Others may find material I didn’t mention to be more important. So do read the book, if your interest is sparked.

I wasn’t expecting Desmet to go in some of the directions he did in parts 1 and 3, but was very pleased with the direction he took. My own philosophical leanings put me on the same vector as Desmet when it comes to a non-materialist alternative that isn’t dogmatically religious. Lobaczewski, too, drops a few hints here and there that would probably put him in the same camp. For example, he is adamant about the importance of receptivity to the existence and experience of what he calls “supernatural causality” (PP, p. 17) or “supra-sensory reality” (PP, pp. 33-34), not as a matter of belief, but as the result of a truly scientific investigation (much like the scientists Desmet quotes conclude).

If we thus wish to understand mankind—man as whole—without abandoning the laws of thought required by objective language, we are finally forced to accept this reality, which is within each of us, whether normal or not, whether we have accepted it because we have been brought up that way or have achieved it through faith, or whether we have rejected faith for reasons of materialism or science. (PP, p. 33)

He’s also humble about the limits of our knowledge of even basic psychological phenomena like memory and association. He even alludes to Pribram’s holonomic theory on a couple occasions (PP, pp. 29, 142). In the notes for these references I repeatedly cited Irreducible Mind: Toward a Psychology for the 21st Century, which I recommend if you’re interested in a fairly comprehensive look at all the phenomena (like psycho-neuroimmunology, to which Desmet refers) suggesting a materialistic worldview of consciousness is inadequate to account for all the data.

To conclude this post, I’ll just add that Lobaczewki’s book is a rigorous attempt fulfill Desmet’s exhortation that “science must consider as one of its most fundamental tasks to map out the structure of the psychological experience, to clarify its laws, and to study the possibilities this gateway to the human being might open up” (PP, p. 174).

One of Lobaczewski’s hopes was that such understanding could inform the creation of a new form of government:

A system thus envisaged would be superior to all its predecessors, being based upon an understanding of the laws of nature operating within individuals and societies, with objective knowledge progressively superseding opinions based upon natural responses to phenomena. We should call it a “logocracy.” Due to their properties and conformity to the laws of nature and evolution, logocratic systems could guarantee social and international order on a long-term basis. In keeping with their nature, they would then become transformed into more perfect forms, a vague and faraway vision of which may beckon to us in the present. (PP, p. 335)2

Conclusion: Ponerologist's Log, Supplemental: Rounding Out the Picture of Mass Formation

The only psychologist to even offer a hint as to an answer to this, to my knowledge, is Kazimierz Dabrowski, but I suspect a full answer can only be found in the mystics, or in a more modern spiritual psychology such as that of G.I. Gurdjieff.

Whether his specific institutional and policy recommendations would work or not is another question—discovery requires experimentation. And those will be saved for when I eventually discuss Lobaczewski’s other book on the subject, Logocracy.

There was an interesting interview with Desmet recently on Brett Weinstein's Dark Horse podcast. They disagreed on the reductionist/materialist aspect, but in a productive way. Worth listening to.

One of the things they touched on was precisely the formation of an 'anti-group', and the danger of mass formation happening there, also. The key to avoiding that trap, according to Desmet, is to ensure strong interpersonal bonds in order to provide stability against the personal-group bonds. Horizontal connectivity preventing the purely vertical connectivity that characterizes a ponerpgenic mass, in other words. It seems to me that this contains much of the answer to the key question - how to effectively combat this situation. Simply speaking out calmly and rationally is surely important, but much more important I think is participating in and providing fora for the development of organic societal bonds, since it is the latter that will actually solve the underlying issue that led to mass formation in the first place.

Another thing he touched on, which is very similar to Gurdjieff's concept of conscious suffering, was that by enduring these difficulties and holding to our principles, our souls and even our bodies actually become stronger. Statements like that, along with other remarks eg the assault on crude materialism, make me suspect that Desmet understands far more than he states directly in public.

Wow....I need to go for a coffee and try to digest this. That was quite the summary.

Excellent work here, Harrison! Blew my mind in places.