At a few points in Political Ponerology, Lobaczewski brings up teleology. In the simplest terms, teleology is the idea that things happen for a purpose. That causation isn’t blind. It is for something. The purpose and function of a molecule, for instance, is as important as how it came to be—perhaps even more important.

Even though purpose is basic to our experience, modern science and philosophical materialism reject it. Maverick geniuses like Rupert Sheldrake, Thomas Nagel, Chris Langan, and Iain McGilchrist embrace it. Here’s how Sheldrake put it:

Purposes exist in a virtual realm, rather than a physical reality. They connect organisms to ends or goals that have not yet happened; they are attractors, in the language of dynamics … Purposes or attractors cannot be weighed; they are not material. Yet they influence material bodies and have physical effects. … Purposes or motives are causes, but they work by pulling toward a virtual future rather than pushing from an actual past. (Science Set Free, p. 130)

Nagel, with typical philosophical understatement, writes:

… if life is not just a physical phenomenon, the origin and evolution of life and mind will not be explainable by physics and chemistry along. An expanded, but still unified form of explanation will be needed, and I suspect it will have to include teleological elements. (Mind and Cosmos, p. 33)

Lobaczewski’s references to teleology are brief and somewhat obscure, but he is hinting at an idea that will make a lot of people uncomfortable. That periods of immense suffering serve a purpose. That there is a teleology to pathocracy. That in some sense, it might be necessary, or even inevitable.

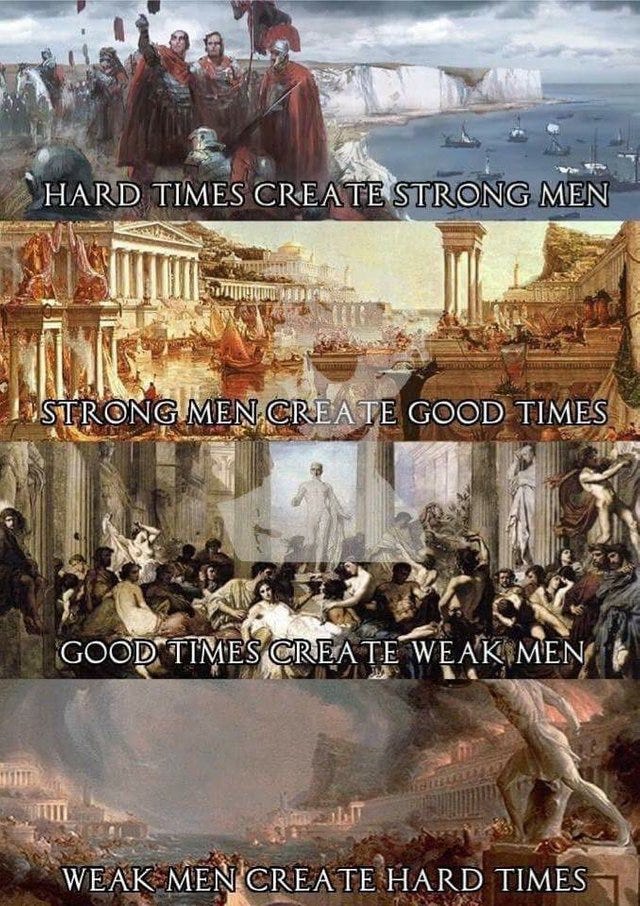

First, in the context of centuries-long societal cycles, he elaborates on how “bad times” follow “good times.” And the suffering inherent in those times is what gives new life to old values. Those values then lead to a new life. Humanity rediscovers what was lost, and is revivified in the process. Basically this, but with more words:

Here’s what he writes:

Those times which many people later recall as the “good old days” thus provide fertile soil for future tragedy because of the progressive devolution of moral, intellectual, and personality values which gives rise to Rasputin-like eras—times of deceit, bitterness, and lawlessness.

The above is a sketch of the causative understanding of reality which in no way contradicts a perception of the teleological sense of causality. Bad times are not merely the result of hedonistic regression to the past; they have a historical purpose to fulfill.1 Suffering, effort, and mental activity during times of pervasive bitterness lead to a gradual, generally heightened, regeneration of lost values, which results in human progress. Unfortunately, we still lack a sufficiently exhaustive philosophical grasp of this interdependence of causality and teleology regarding events. It seems that prophets were more clear-sighted, in the light of the laws of creation, than philosophers … and others who pondered this question. (p. 58)

Next, in the context of the practical understanding common people acquire when they live under pathocracy, he writes:

This new understanding is incalculably rich in casuistic detail [i.e. case-based reasoning, how to act in specific situations]; I would nevertheless characterize it as descriptive, even overly literary. It contains practical knowledge of the phenomenon in the categories of the natural moralistic worldview, correspondingly modified or warped in accordance with the need to understand matters which are in fact outside the scope of its applicability. This also opens the door to the creation of certain doctrines which merit separate study because they contain a partial truth, such as the teleological or demonological interpretations of the phenomenon. (p. 254)

In other words, common understandings of the type you might read in great works on National Socialism and Communism are valuable, but the writers are missing some key ingredients. They might even take a teleological or a demonological view of totalitarianism. And while there are truths in these approaches, they too lack what ponerology’s got: a clear understanding of the psychobiological underpinnings of the phenomenon.

But still, what might the “partial” truths be?

Next, he writes:

Insofar as the appearance of pathocracy in various guises throughout human history always results from human errors which opened the door to the pathological phenomenon, one must also look on the other side of the coin. We should understand this in the light of that underrated law, when the effect of a particular causative structure has a teleological meaning of its own. (p. 297)

He also describes the normal people in pathocratic nations in the mid-1980s as showing “a feel for a certain teleological meaning to phenomena, in the sense of a historical watershed” (p. 317). In other words, as if some great purpose, some new meaning, were about to emerge.

In a section on how to deal with pathocrats long in power (and unwilling to give it up, lest they be lynched), he writes:

We should partially accept their feeling that they are fulfilling an historical mission or even functioning as the scourge of God. (p. 309)

Perhaps something like this: “Sure, we may be directly or indirectly killing millions, but it’s a small price to pay. Millions dead today will prevent billions from dying tomorrow! Humanity is weak, lazy, and flawed. We are purifying them, and in a generation or two (or a hundred), they’ll be thanking us for doing what needed to be done. I mean, how else could we have upped our steel production?”2

So now we have some hints.

Pathocracy seems designed to produce the ideal conditions for the rediscovery of the values we have spurned for the cheap substitute of hedonism. Humanity gets weak. It gets selfish, superficial, complacent, self-satisfied. We let our body go, and disease takes root. We become arrogant and casually duplicitous. Most likely our ruling classes are the worst offenders, but they’re not the only ones—not by a long shot.

Pathocracy can also teach us what we did wrong to lead to this in the first place. In other words, the process initiated by human failings and catalyzed by pathocracy fulfills a separate purpose: revealing the initial errors that opened the door to mass evil. We can learn our lesson. If the pathocracy is religious in nature, this process can refine the religion in question—same goes for a secular ideology.

Shafarevich closes his book on socialism with the following words:

… if we suppose that the significance of socialism for mankind consists in the acquisition of specific experience, then much has been acquired on this path in the last hundred years. There is, first of all, the profound experience of Russia, the significance of which we are only now beginning to understand. The question therefore arises: will this experience be sufficient? Is it sufficient for the entire world and especially for the West? Indeed, is it sufficient for Russia? Shall we be able to comprehend its meaning? Or is mankind destined to pass through this experience on an immeasurably larger scale?

There is no doubt that if the ideals of Utopia are realized universally, mankind, even in the barracks of the universal City of the Sun, shall find the strength to regain its freedom and to preserve God’s image and likeness—human individuality—once it has glanced into the yawning abyss. But will even that experience be sufficient? For it seems just as certain that the freedom of will granted to man and to mankind is absolute, that it includes the freedom to make the ultimate choice—between life and death. (Socialist Phenomenon, p. 300)

I think Shafarevich nails it: “the acquisition of specific experience.” A common observations of those who lived through communism in the twentieth century is that people in Western countries strike them as extremely naive in this area. They just don’t get it. And not having experienced it for themselves, they blindly stumble into it. Like a parent’s warning to his teenage child about certain suffering should a particular course of action be followed, any advice will fall on deaf ears. They just need to make their own mistakes and hopefully learn from them in the process.

This is what we’re seeing today: people falling head first into totalitarianism with a somewhat forced smile on their faces. Any warnings are met with sneers of contempt, derisive laughter, and genuine bafflement. They honestly feel we’re doing the right thing, or at least not screwing up too badly.

Lobaczewski, however, is optimistic. He thought that the experience of Soviet pathocracy was sufficient, for Russia, the world, and the West. But only because the experience was sufficient to lay the groundwork for ponerology to develop. Without ponerology—the scientific elaboration of the “practical understanding” acquired by the people who lived under communism—it won’t be sufficient, and we will be fated to “pass through” the abyss “on an immeasurably larger scale.” As Mattias Desmet points out, this time around the mass formation is practically global.

Whether Lobaczewski was right or not, we may never know. Maybe his optimism was misplaced? At the very least, it’s worth a shot, because nothing else has worked. Revolution doesn’t work. Stable social and political systems inevitably decay. Warfare is inefficient and mostly results in a depletion of any given country’s talent pool. It may be successful in regime change, but regime change without identifying and treating the root problems is either a temporary solution at best, or only makes things worse.

So in a certain sense, maybe pathocrats are the “scourge of God”—agents of purification through mortification, like a human Black Death, Great Flood, or a civilization-destroying cometary bombardment.

If that idea makes you uncomfortable, here’s how I see it. It’s not as if there is some Old Man in the sky hurling comets at humanity every time they get a bit crazy, or unleashing pandemics that wipe out significant percentages of the population to “cleanse” humanity. Surely the Old Man would have more sophisticated means to separate the wheat from the chaff. No, that is the moralistic vision carried over from Plato (Atlantis) via Judaism (the Flood): cluster bomb morality.

The way I see it, it is more of a law of the universe, like: if you step into a wood-chipper, the result will be messy. Humanity is stepping into the wood-chipper, like it has done so many times before. We are behaving in certain ways that make some form of mass destruction—maybe psychological, maybe physical—inevitable. When our individual and collective actions stray too far from the set of conditions that make harmonious living possible, chaos makes its entrance. We’re simply walking the path of the pathocratic attractor.

I’ll close this one out with a quote from one of my favorite writers, Arthur Versluis. The book is about seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Christian theosophy. The subject is the wrath of God. He writes:

… even though it is our individual task to transform wrath into love, wrath has its place in the scheme of things; without it one could not be tested, nor could one transmute it into love through spiritual alchemy. … rather than striving to separate oneself from wrath, one embraces it, absorbs it, and transmutes it into love. For wrath and the wrath world has a necessary place in the cosmos, and this place is one of purification.

After all, each of us has sown discord, made mistakes, sinned. If we agree with the premise that divine mercy and divine wrath are in an ultimate sense one, the difference being in the perception of the individual soul, then perhaps we can see how to be tested and purified in the divine wrath is, finally, to be invested with the robe of glory and peace. The theosophers sometimes express this as passing the flaming sword back into paradise … (Wisdom’s Children, pp. 204-205)

Just a note here that Lobaczewski isn’t a Marxist. He doesn’t discount the idea that there might be purpose and even perhaps “attractors” at work in history, but they are not so rigid and deterministic as those envisioned by Marxisms stages, e.g., primitive communism, followed by slave society, feudalism, capitalism, and then socialism. Marx was wrong, but that doesn’t mean teleology is wrong.

Or today, “How else could we have stopped global warming?”

This is just what I needed, Harrison. And it's what a lot of people need, even though they don't know it.

Please pardon what is going to initially sound like a Personal Feels story. It's not; it's about the concept.

I've been in longterm psychotherapy since the rupture and the Cluster B awakening in my life 6 years ago. There have been times that were so difficult all I wanted to do was complain to my therapist about the pointless suffering.

He reminds me that it's not pointless. It's necessary. We must all suffer at some times in order to gain the things that your article talks about. We must be forced to think and feel our way through it. That's how we learn what is valuable and worth striving for, and how to correct ourselves when we stray from a productive path.

That’s some strong meat you’ve got here. I’ve been feeling the same, and your eloquent words were very helpful for me in getting a better grasp of the broad dimensions of our current state.

I’ve been viewing this as at least partially a purification process, coupled with what amounts to a much needed spanking for His Children by God. Lately my mind has been drawn to passages from the book of Hebrews. Chapter 12:4-13

“You have not yet resisted to the point of shedding blood in your striving against sin; and you have forgotten the exhortation which is addressed to you as sons,

“MY SON, DO NOT REGARD LIGHTLY THE DISCIPLINE OF THE LORD,

NOR FAINT WHEN YOU ARE REPROVED BY HIM;

FOR THOSE WHOM THE LORD LOVES HE DISCIPLINES,

AND HE SCOURGES EVERY SON WHOM HE RECEIVES.”

It is for discipline that you endure; God deals with you as with sons; for what son is there whom his father does not discipline? But if you are without discipline, of which all have become partakers, then you are illegitimate children and not sons. Furthermore, we had earthly fathers to discipline us, and we respected them; shall we not much rather be subject to the Father of spirits, and live? For they disciplined us for a short time as seemed best to them, but He disciplines us for our good, that we may share His holiness. All discipline for the moment seems not to be joyful, but sorrowful; yet to those who have been trained by it, afterwards it yields the peaceful fruit of righteousness. Therefore, strengthen the hands that are weak and the knees that are feeble, and make straight paths for your feet, so that the limb which is lame may not be put out of joint, but rather be healed.

And the last verse of the chapter “Our God is a consuming fire.”

It’s going to continue to heat up, of that I’ve little doubt.