“A Midwestern Doctor” (AMD from now on) recently updated and republished a piece on the link between antidepressants and mass shootings. I disagree with the main argument, but I still recommend reading it for some of the points it makes, which I will discuss below. Here’s the article:

First, AMD makes a point with which I’m in complete agreement:

I and many colleagues believe the widespread adoption of psychotropic drugs has distorted the cognition of the demographic of the country which frequently utilizes them (which to some extent stratifies by political orientation) and has created a wide range of detrimental shifts in our society.

The main thrust of the article is the mostly unreported (and thus unknown) link between antidepressant use and violent behavior, including homicide and suicide:

SSRI homicides are common, and a website exists that has compiled thousands upon thousands of documented occurrences.

AMD links these reactions with drug-induced akathisia:

Akathisia, an extreme form of restlessness is defined as a psycho-motor disorder where it is extremely difficult to stay still. What this definition omits to mention is that akathisia is incredibly unpleasant to the degree that many individuals who experience it frequently commit suicide or homicide (or both). One of the earliest reports from patients with drug-induced akathisia was: “They reported increased feelings of strangeness, verbalized by statements such as ‘I don’t feel myself or ‘I’m afraid of some of the unusual impulses I have.’”

Here’s Dr. Jordan Peterson describing his own experience with akathisia when coming of benzos:

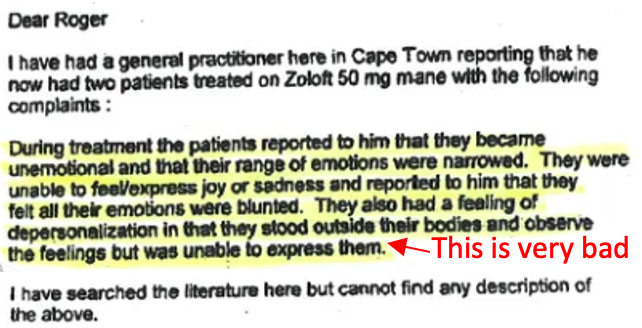

AMD also cites this revealing exchange from “a clinical investigator to Pfizer”:

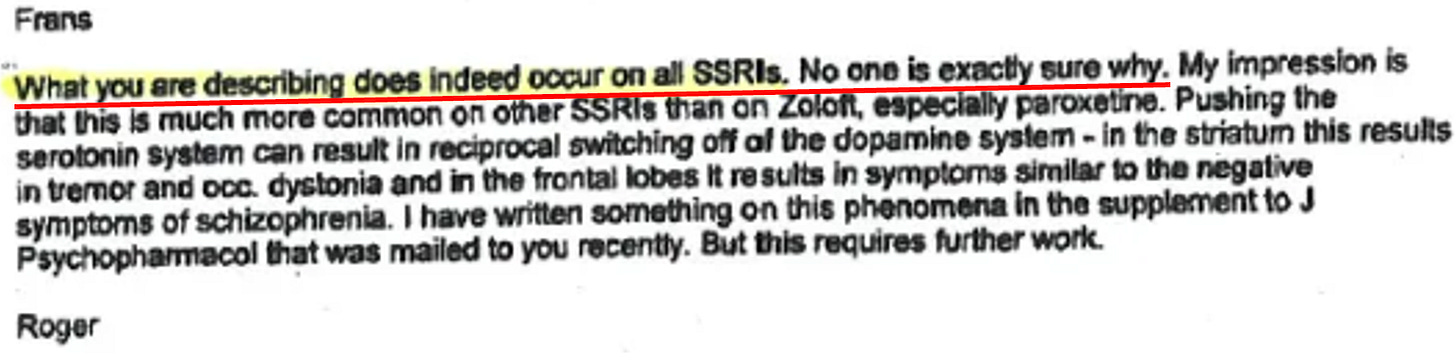

Pfizer’s response:

AMD cites Peter C. Gøtzsche on these violent outbursts:

These violent events occur in people of all ages, who by all objective and subjective measures were completely normal before the act and where no precipitating factors besides the psychiatric medication could be identified.

The events were preceded by clear symptoms of akathisia.

The violent offenders returned to their normal personality when they came off the antidepressant.

It’s not as if your chances of experiencing such an episode from antidepressants are high (e.g., a 50% chance or greater). However, as AMD points out, if even 0.1% of users of these drugs experience a violent reaction, that in itself would be strong enough a signal to warrant asking some big questions, at the very least. When it comes to drug-induced homicide, “any elevated risk in this regard should be viewed as unacceptable without any exceptions.” Again, I agree. AMD cites one study, for instance, that found that “0.65% of the patients in clinical trials became hostile on Paxil compared with 0.31% on placebo.”

Here’s a small sample of the deadly results of these types of reactions:

Male, 18 years, Prozac, sister was comatose after a car crash, violent akathisia for 14 days, killed his father four days after he ran out of pills.

Male, 35 years, Paxil, distressed by “on and off” relationship with mother of his child, stabbed former partner 30+ times to death after 11 weeks of akathisia.

Male, 16 years, Zoloft and Prozac, depressed, struggled at school, and the girlfriend left him, attempted suicide on both drugs, killed therapist in hospital after 11 weeks.

Female, 35 years, nortriptyline, distress due to husband’s drinking, killed teenage daughter in toxic delirium after three days.

Female, 25 years, Celexa and Effexor, marital distress, several suicide attempts on both drugs, jumped in front of a train with her child while on citalopram.

As to why a small minority of people have these reactions, AMD writes:

Individuals with a mutation in the gene that metabolizes psychiatric drugs are much more vulnerable to developing excessive levels of these drugs and triggering severe symptoms such as akathisia and psychosis. There is a good case to be made that individuals with this gene are responsible for many of the horrific acts of iatrogenic (medically induced) violence that occur, however to my knowledge, this is never considered when psychiatric medications are prescribed.

That sounds plausible to me, and I’d like to see research looking for causes like this. (Same goes for adverse vaccine reactions. What are the vulnerabilities? Can they be known in advance, to avoid negative reactions with long-term or fatal outcomes?)

However, AMD then makes this statement:

As far as I know (there are most likely a few exceptions), in all cases where a mass school shooting has happened, and it was possible to know the medical history of the shooter, the shooter was taking a psychiatric medication that was known for causing these behavioral changes.

Based on my own reading on the topic, this is simply untrue. AMD cites this article (inspired by a Facebook post), for instance, which begins: “Nearly every mass shooting incident in the last twenty years, and multiple other instances of suicide and isolated shootings all share one thing in common, and it’s not the weapons used.” It includes a list of dozens of murders and mass killings, including the name of the shooter and the drugs they were (allegedly) on.

Dr. Peter Langman probably knows more about school shootings than anyone. He has authored several books on the subject, and his website is the best resource on the subject on the Internet, including court documents, medical records, investigation reports, and more. In his article, “Psychiatric Medications and School Shootings,” Langman quotes a sample from the above list:

Fifteen year old Kip Kinkel (Prozac and RITALIN) shot his parents while they slept then went to school and opened fire killing 2 classmates and injuring 22 shortly after beginning Prozac treatment.

Luke Woodham aged 16 (Prozac) killed his mother and then killed two students, wounding six others.

Michael Carneal (Ritalin) a 14-year-old opened fire on students at a high school prayer meeting in West Paducah, Kentucky. Three teenagers were killed, five others were wounded, one of whom was paralyzed.

Andrew Golden, aged 11, (Ritalin) and Mitchell Johnson, aged 14, (Ritalin) shot 15 people killing four students, one teacher, and wounding 10 others.

He writes:

Based on my research, this list is wrong in many ways. Kip Kinkel (Thurston High School) did not murder his parents as they slept and he had not just begun treatment with Prozac. Kinkel first shot his father while he was talking on the telephone, and then shot his mother after helping her bring in groceries from the car. More importantly, Kinkel was not on any medication when he went on his rampage. He had taken Prozac and Ritalin in the past but not anywhere near the time of his attack (details will be discussed below).

Regarding Luke Woodham (Pearl High School), I have not found any reliable source that states he was on Prozac. I have read books, book chapters, and many articles about Woodham and not found any mention of Prozac. The coverage by The New York Times and many other sources don’t mention it. Even in his court cases where he appealed his sentence on numerous grounds, including insanity, there is no mention of his being on Prozac. Mental health professionals testified about Woodham’s psychological state, but they made no reference to prior treatment or medication. Unless other information becomes available, Luke Woodham should not be on the list of school shooters who took psychiatric medications.

The shooting by Michael Carneal, as well as that by Andrew Golden and Mitchell Johnson, were investigated by Dr. Katherine Newman and her team of researchers. They interviewed 163 people in the towns where the shootings occurred (West Paducah, Kentucky, and Jonesboro, Arkansas). This was the most thorough investigation of these shooters that anyone has conducted. Regarding Golden and Johnson, Newman’s team concluded, “There is no evidence that either boy was on any form of medication.” Similarly, though the research team explored Carneal’s mental health history, there was no report that he had been diagnosed with any psychiatric disorder or prescribed any psychiatric medication. Golden, Johnson, and Carneal should not be on the list of medicated shooters.

Thus, as far as I can determine, all five claims that Kinkel, Woodham, Carneal, Golden, and Johnson were on medication at the time of their attacks are wrong. Nor are these the only shooters for which such claims have been made.

The whole article is worth reading. Langman has another pdf listing the results of his own research on this subject: “Tally of Shooters’ Use of Psychiatric Medications and Substance Abuse.” The tally includes 68 shooters. 66%1 had no discernible past, recent, or current medication use (15% had current or recent use, defined as within a month of the attacks; 19% had past use).

This matches the results of this paper, which looked at 49 school shootings and found evidence that about half of them were either confirmed or highly suspected to have been prescribed such meds sometime prior to their attacks:

From information available, 21 shooters (43%) had received some form of mental health treatment prior to the shooting. For the remaining individuals, there was either no indication (hard to prove or identify a negative) or it was unknown (not mentioned either way). Although not definitive, this observation strongly argues against the notion that most school shooters were prescribed psychotropic medications prior to the event. Also of note twelve (24%) of the individuals had prior interactions with law enforcement (e.g., arrests, received warnings).

… There does not appear to be a strongly documented pre-event history of school shooters being followed by traditional licensed treatment providers (MD, DO, APRN) who prescribed psychotropic medications. …

Twenty-three individuals (47%) had been prescribed a psychotropic medication or were probably prescribed (e.g., reported psychiatric hospital admission even if specifics of treatment are unknown) a psychotropic medication at some point prior to the event (Table 3). When it could be determined, the psychotropic medication classes prescribed were as follows: 11 (22%) had a history of being prescribed an antidepressant, three (6%) an antipsychotic agent, three (6%) benzodiazepines, two (4%) stimulant medications and one sleeping medication. Although there were some cases where the individuals had clearly seen treatment providers within 3 months of the event (e.g., 2004 Columbia High School, 2005 Red Lake High School, 2013 Sparks Middle School, 2013 Arapahoe High School), there were also cases where the individual had made a clear decision to stop mental health treatment (e.g., 2009 Hampton University, 2017 Rancho Tehama Elementary School). For the vast majority of cases reviewed, no reasonable determination could be made regarding whether those with a treatment history were still active or compliant with treatment at the time of the shootings.

Additionally, to AMD’s point, if akathisia is the cause of violent reactions, there should be signs of such in the case of these school shooters. But as far as I can tell, it isn’t. Some shooters show indications of psychosis, but by no means all, and those that do often had a history of psychosis. AMD brings up an objection of this sort:

One of the most common arguments used to dismiss the link between psychiatric medication and violent behavior is the notion that the people who have mental illness are the ones who receive those medications, so the correlation observed may be due to the pre-existing mental illness rather than the medication. As this article has shown, many people (and quite a few readers) who were completely normal prior to the SSRI developed those tendencies after they started the medication.

Indeed, but does this apply to school shooters? Here’s another paper that influenced my previous article on the subject (along with Langman’s work):

The majority of assailants (87.5%) had misdiagnosed and incorrectly treated or undiagnosed and untreated psychiatric illness. Most of the assailants also experienced profound estrangement not only from families, friends, and classmates but most importantly from themselves. Being marginalized and interpersonally shunned rendered them more vulnerable to their untreated psychiatric illness and to radicalization online, which fostered their violence.

In my article I made the connection to personality disorders, quoting Langman’s three categories of shooters:

Psychopathic shooters are narcissistic, entitled, lacking in empathy, and sometimes sadistic. Some are abrasive and belligerent; others are charming and deceptive.

Psychotic shooters have either schizophrenia or schizotypal personality disorder, with a combination of psychotic symptoms (hallucinations, delusions, disorganized thoughts/behavior), eccentric behavior and beliefs, and severely impaired social/emotional functioning.

Traumatized shooters grew up in chronically dysfunctional families characterized by parental substance abuse, domestic violence, physical abuse, sometimes sexual abuse, frequent relocations, and changing caregivers.

Perhaps drugs contributed to some of the school shooters’ crimes. After all, while there’s no evidence that all, or even close to all, of them were on psychiatric meds, the number who were is still higher than that of the general population closest to their age range.2 But it’s by no means an essential contributing factor to the phenomenon as a whole, at least not according to those who have looked into the subject in depth. Far more important, as far as I can tell, are psychopathy, personality disorders like antisocial, narcissistic, schizoid and schizotypal, as well as psychotic disorders like schizophrenia.

That said, I want to reiterate that I agree wholeheartedly with AMD’s other main points, specifically on the damages these drugs are known to cause.

And that leads me to one final point. On another study, AMD writes:

The authors of this paper hypothesized that the violent actions following the usage of SSRIs may be explained by their tendency to trigger akathisia, emotional blunting, and manic or psychotic reactions.

One of Lobaczeski’s “ponerogenic factors” in addition to psychopathy is what he called “drug-induced characteropathy.” While he was referring to permanent changes to personality caused by drug-induced brain damage, I think we should add the temporary effects of prescribed psychiatric medications to the list. The central feature he mentions contributing to the ponerogenic role of this type of brain dysfunction: emotional blunting.3

And given the subject matter of the short article I posted on the latest school shooting, we may have to take this into consideration more as time goes on:

Testosterone Therapy Increases Anger Expression And Control In Transgender Men, Especially If Their Periods Persist

People undergoing female to male gender-affirming testosterone treatment are likely to experience increased aggression — which may be worse if their periods persist.

Interestingly, anger expression and anger control increased:

During the 7-month testosterone treatment, anger expression and anger control both increased. Specifically, there was a significant change in the feelings of anger towards other persons or objects and towards themselves.

The authors of the study say it’s important to note, however, that despite the increase in anger expression, there were no reports of aggressive behavior, self-harm, or psychiatric hospitalization.

The question for me, as with the one I have for antidepressants and vaccines: is there a subset of the population for whom anger control will not also increase, and who are at risk for increases in actual aggressive behavior?

His tally has an error, listing the percentage as 69%. The 47 listed under the “none” column should read 45.

According to the CDC, “During 2015–2018, 13.2% of adults used antidepressants in the past 30 days (Figure 1). Use was higher among women (17.7%) than men (8.4%). The percentage of antidepressant use increased with age, from 7.9% among adults aged 18–39 to 14.4% for those aged 40–59 to 19.0% for those aged 60 and over.” Using Langman’s tally, that would suggest school shooters had about double the rate compared to the general population (15%, compared to 8%).

Political Ponerology, pp. 98-100.

You are talking about the USA, right ?

Do such mass shooting occur in other countries ?

Are the said drugs supplied with similar prevalence in other countries ?

Are the shooters confined to a specific age range ?

Thank you for helping me correct my notions about the relevant facts, Harrison! I had been trusting the very reports that you just so kindly debunked.