Control through Calculated Ferocity

Chapter 4 of Karen Mitchell's thesis - the core attributes of the dark personality

“It is truly terrifying being up against them. It is also isolating. It is also very difficult to describe. Once you know the type you can recognise it, even when others can’t see it. They are highly dangerous people.” (Category 2 participant)

Now for the stuff we’ve all been waiting for. Chapter 4 of Karen Mitchell’s thesis summarizes the results of her study, listing each of the core attributes of the persistent predatory personality, with quotations from her various participants. But first, an important point: “the data indicate that all adults of DP are equally as exploitative, dangerous, manipulative, and self-focused.”

In other words, it’s not as if non-incarcerated predators are just “a little bit” psychopathic. No, they’re the full deal. They just differ in other ways.

The data indicate those of DP who remain out of prison are more likely to be of higher intelligence and socioeconomic status, have better impulse control capability, and are more adept at creating compelling facades, leading double lives, the ‘dark’ side of which most people are unable and/or unwilling to see, even where there may be subtle or even obvious indicators. The data also indicate higher functioning people of DP engage more effectively in underhanded tactics that prevent exposure and accountability, are better at grooming or manipulating others to support them, and are more likely to harm using methods that are subtle, ongoing and leave no evidence, resulting in emotional and mental ‘torture’ which their targets/victims struggle to recount to others.

So rather than being somehow “less” psychopathic, the successful ones are arguably just better psychopaths.

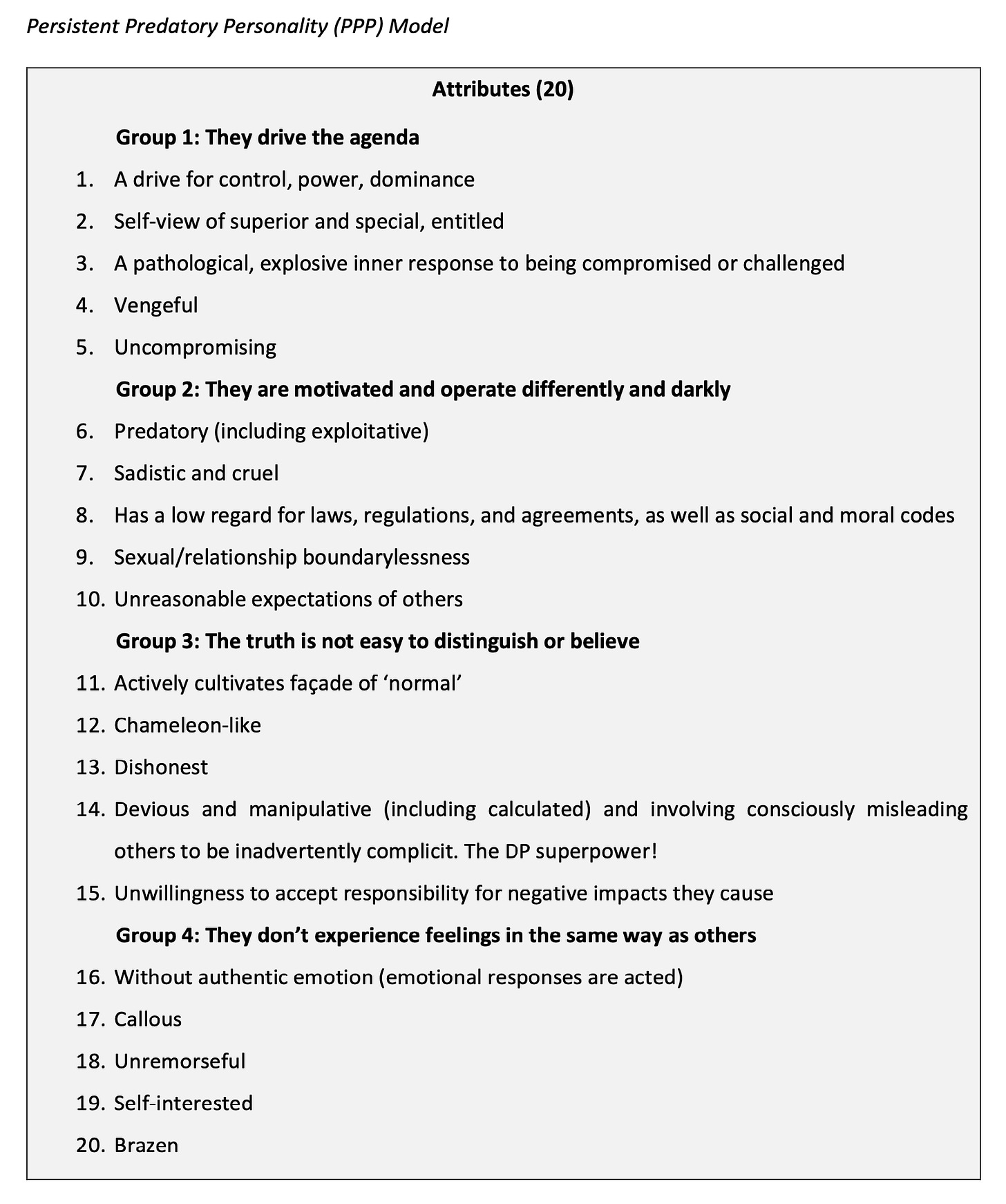

Mitchell’s analysis yielded 20 core attributes. She argues that all 20 are common to all PPPs. They differ between individual PPPs only in their specific behavioral manifestations, which depend on “context, opportunity, personal circumstance, and personal preference.” For instance, an incarcerated PPP may not be able to manifest vengeance to the degree that he would while out of prison. Additionally,

While the findings indicate that all people of DP break laws, regulations, and agreements, as well as social and moral codes, the data also show that if someone of DP is of higher socioeconomic status, they are less likely to manifest this attribute as they can pay or bribe other people to break laws and regulations on their behalf.

As noted in my prior article, Mitchell also identified 25 common tactics, as well as a handful of “differentiators,” i.e., unique and sometimes contradictory capabilities and values. Here Mitchell makes what I consider a revolutionary insight: “The data indicate researchers have developed new iterations of DP based on these differentiators rather than focussing on refining our understanding of shared attributes.” In other words, many of our current conceptions of dark personalities are probably just descriptions of subsets of PPPs with a common differentiator (or set of differentiators). The researchers who come up with such models mistake a secondary feature for an essential attribute. For example, one researcher might say that psychopaths by definition have low impulse control, when in fact they can have either low or high impulse control while sharing the same common set of core attributes.

Before discussing the 20 attributes, Mitchell has a section describing the “dark core” of the PPP—their “profoundly unacceptable ‘darkness.’” As she puts it, “all people of DP are deeply malevolent and dangerous,” and those who remain out of prison are “able to impose harm equally as destructively in covert ways while adopting strategies to avoid exposure and incarceration.” This dark core affects non-psychopaths in a characteristic way.

(For reference, Category 1 = personality researchers, Category 2 = behavioral researchers, Category 3 = expert forensic practitioners, Category 4i = non-forensic professional practitioners, Category 4ii = non-forensic corporate practitioners, Category 4iii = non-forensic community practitioners.)

She quotes one of her Category 4i participants, who lists some of the typical responses of victims/targets of DPs: suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, depression and anxiety, self-harm behaviors (eating disorders, drug and alcohol dependence, cutting), immense overwhelm and despair, feeling as if they are going “crazy,” feeling “trapped and stuck like there is no way out of ‘this hell’ except to die,” losing the ability to work, struggles attending school, strained relationships. And crucially, “Victims often do not know who to turn to for validation and support. Victims do not feel believed and start to despair at the isolation of their experience.” Mitchell expands on this observation:

The findings show that people who have not been targeted by or worked extensively with people of DP and/or their target victims find it hard to comprehend, believe, and accept the complex manoeuvring and dark motivation of people of DP.

The findings also indicate that the motivations of people of DP are so profoundly different from the rest of the population that it is challenging for those who have not been targeted, including many mental health professionals, to accept the depth of ‘darkness’ and attributes and behavioural manifestations that stem from this dark core …

Lobaczewski refers to this blindness in a couple ways, first as a product of the “common psychological worldview.” This might manifest as pollyannaish interpretations such as “Oh, he must have had such a bad childhood,” or “He must really be hurting underneath all that aggression,” “I just know that inside is a person who just wants to be loved,” or even a dismissal that he has done anything wrong. Second, he calls this phenomenon the first criterion of ponerogenesis: evil spreads when people can’t identify it for what it is.

Our unfamiliarity with such malevolence, combined with their skill at avoiding transparency, can cause us to misinterpret their actions. For example, “many small acts that together occur as ‘torture’” may seem to an outsider “may seem like one-off …innocuous behaviours when recounted to others.”

“People think that they are exotic and complex. Instead, they are simple and dangerous. … Normal people don’t get how these people toxify the world around them.” (Category 4ii)

“I guess it highlights how the face of evil is so benign.” (Category 4iii)

Key elements evident in the quotations include the difficulty for those who have not been targeted by someone of DP to understand and accept the extreme nature of the harm they cause when it is not physical; misconceptions about the true nature of people of DP; a reluctance to accept that someone they know may be so malevolently motivated; and that most people miss the signs that the targets/victims recognise that indicate people of DP. … many people do not want to believe the motivations of those of DP because it is just too awful to dwell on. … Several participants discussed the difficulty for targets/victims to be believed, the nature of harm was so bizarrely inhumane.

A more basic response to psychopathic malevolence is simply fear. Mitchell devotes a section to this response. Out of the expert practitioners, 72% reported experiencing fear in the presence of a DP; 74% reported experiencing the same while not in their presence. In contrast, only 40% of the researchers experienced such fear in a DP’s presence; and only 20% when not in their presence. “At least one researcher in the study reported they had never, to their knowledge, been in the physical presence of someone of DP.”

Specific fears ranged from concerns of the DP ruining their career, slandering them, physically assaulting them, destroying their property, sabotaging their relationships, ruining them financially, etc. As one of the 4iii participants put it: “anything is possible as a form of revenge.” Another described it like this:

“I think the sense of superiority and quiet menace has given rise to this fear. The amusement in their eyes. You can almost hear the sinister thoughts through the silence. It creates a sense of foreboding that this person will store up revenge to be exacted at a later date.” (Category 4iii)

By far the most frequently mentioned theme in the Delphi survey and follow-ups was “dangerous and harmful” (1,170 mentions). As Mitchell points out, however, this is not an attribute; it’s an outcome. The second most popular theme, and the highest-rated attribute, was “driven by control, power, dominance” (654 mentions). These were also the two highest-rated themes when participants were asked which attribute drives most DP behaviors. So if we wanted to capture the DP in the smallest possible nutshell, we might say they are dangerous and harmful people driven by control, power, dominance.

The model that emerged from the thematic analysis is the persistent predatory personality. Mitchell justifies the name like this. “Persistent,” because DPs cannot be “cured”; their sense of superiority precludes them from believing there is even anything wrong with them. “Predatory,” because, like predatory animals, they are “very different to those of most other human beings”; “they seek out the vulnerable, weaken them, isolate them, and use their pain or discomfort for entertainment, often harming or destroying them, while staying hidden and blending into the environment when they can.” And “personality,” because the model describes a discernible cluster of attributes.

These 20 attributes break down into four conceptual groupings. Here’s what they look like:

Attribute 1: Driven By a Need for Control, Power, and Dominance

The most commonly cited attribute in the study, Mitchell defines this as “an intense, all-pervasive drive for people of DP to dominate their world and the people in it using tactics ranging from the more subtle and covert to the transparent and evident.” Some relevant excerpts from the interviews:

“A constant desire or perhaps need to be in control of any situation to enable an outcome beneficial at its core to that individual at the expense of all else.” (Category 4i)

“I think why they enjoy manipulation so much is it gives them that sense of power, because they can control that other person.” (Category 3)

“They keep themselves ingrained in their victim’s life through extremely complex manoeuvring of other people, of circumstances, of facts such that the other person is eventually ‘destroyed’ professionally, reputationally, socially, and/or financially. It is a web of control and destruction which often involves many characters and situations. It can extend for years.” (Category 4i)

“DP engage in an extensive array of strategies to ensure they control their environment including sacking people; creating what I would call ‘big lies’ to undermine people who get in their way or who may expose them or who they don’t like or who they just decide to pick on; cultivating a network of supporters who will stick up for them regardless and who have a particularly positive view of the DP from the way the DP has groomed them or is getting something out of supporting the DP; by withholding information.” (Category 4ii)

Several of the participants linked this feature with sadism (a separate attribute), saying, for example, that the DP “gains a sense of power from the pain inflicted.”

Things get ugly when their control is challenged. “Loss of control for people of DP is profoundly unpalatable.” The DP establishes a set of rules for others. Noncompliance is punished; compliance rewarded.

“You learn that it is dangerous, either emotionally or physically, to ‘upset’ them and will always be walking on eggshells.” (Category 4iii)

Attribute 2: Self-View of Superior and Special, Entitled

Mitchell defines this attribute as follows: “a deeply held inner belief that they are better than other human beings and have the right to behave in any ways that please them, regardless of who it might harm or disadvantage.” As Lobaczewski puts it, they view us as from a distance, as “not quite conspecific,” i.e. like an inferior species.

“They have a cold-blooded sense of entitlement by which the world is a chess board, and all the participants are but parts to be moved around and utilised by the DP with no sense of the impact on them. They exist as objects and have little or no value in themselves.” (Category 4i)

“The perpetrator shows clear enjoyment of causing harm to multiple others yet poses as a heroic ‘Jedi knight’ type and justifies his actions in the guise of ‘fighting evil’. His entire public personality is a construct, and he utilises aliases to do harm and hide his wrongdoing.” (Category 4i)

Conning others successfully confirms this sense of superiority in their minds. Other literature references “duping delight,” and it’s not uncommon to find statements from incarcerated PPPs like, “Well, if he was dumb enough to fall for it, he deserved it.” PPPs also lack any sense of normal reciprocity or obligation.

Attribute 3: A Pathological, Explosive Inner Response to Being Compromised or Challenged

Psychopaths are often described as cold-blooded and emotionless. However, PPPs display “hot anger” in three situations: “where their view of themselves as superior is challenged, where they are thwarted in achieving a goal, and where they are ‘exposed’ or at threat of being exposed.” Participants describe this anger as “off-the scale” and “profoundly upsetting” (Category 3).

One manifestation of this takes the form of “a sudden, ferocious outburst accompanied by physical behaviours, possibly physical violence, and/or possible destruction of property.”

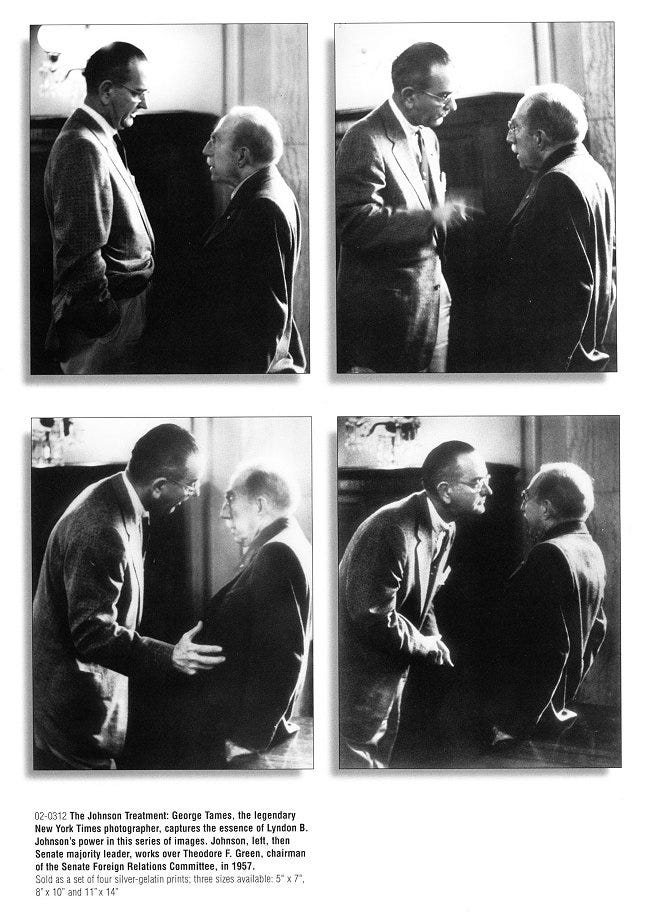

In many cases, physical use of the body is engaged, not to physically harm but to intimidate and cause fear. The findings indicate this might include standing over someone, stepping into the target/victim’s body space, moving their face closer to the target/victim’s face, or gesturing with a finger at the person’s chest. [See the image of Johnson above.]

“They stand over you. Make their body imposing. The anger is palpable, they often bring their face close to you. Point their finger at you in a stabbing motion. There is sudden silence like in the eye of a tornado and their eyes turn black and they speak slowly and forcefully, and it is extremely intimidating.” (Category 4ii)

The reference to the eyes is fascinating and deserves more research:

There is substantial discussion in the data about the deadness or coldness of the eyes and how the ‘eyes turn black’ at the point of pathological anger. This was an interesting issue to emerge from the data: the nature of the eyes when pathological anger is present. This issue is not referenced in the academic literature; however, it is referenced in the popular press and was discussed extensively in this study.

PPPs with greater impulse control are better able to restrain this response. Their vengeance may come years later and may be effected covertly. Participants describe an additional response to situations that induce their anger: intense calmness, “often accompanied by subtle body language and mannerisms that cause ‘terror.’”

“They become hyper-focussed and cold. They do not express a lot of overt rage.” (Category 3)

“A smirk and smile that said, ‘I will get what I want from you.’ That can generate fear as much as an exhibition of rage.” (Category 3)

Nonphysical forms of harm were mentioned more than twice as often (765) as physical ones (331). “The data indicate that one reason the pathological, explosive inner response is so frightening is that it seems to be universally followed by some kind of punishment or revenge.” This is perhaps why so many of the expert practitioners have felt fear both in and out of the presence of a DP. They are “programmed” to exact vengeance, and one way or another, they will attempt to get it. Which leads us to the fourth attribute:

Attribute 4: Vengeful

One of the most powerful themes emerging from the data in relation to vengeance is the certainty that a person will be harmed if they displease someone of DP and the terrifying body language and signals that communicate this to the target/victim, which the data indicate others are unlikely to understand.

“When someone does something they do not like or someone gets an advantage over them, they come on hard with public humiliation, sacking, taking legal action against the victim/s, slamming the victim publicly in some way, creating rumours about the victim.” (Category 4ii)

“He had a filing cabinet in his head and then at a time when he was not feeling on top or in control, he would literally take someone out of the filing cabinet, and he would wreak revenge on that person.” (Category 3)

“They continue to exact revenge on the victim in covert ways long after that victim has been psychologically/emotionally/financially/socially broken.” (Category 2)

“In coercive control, perpetrators can give subtle signals to their victims that they are angry and are going to punish them. It is often a movement of the head, a look in the eyes or something similarly subtle which they can give in front of others without others noticing, but the victim notices and is terrified.” (Category 2)

Attribute 5: Uncompromising

Lobaczewski several times references the psychopath’s “hyperactive” or persistent nature, as well as their “pathological egotism” (i.e. they’re never wrong and forcefully impose their views on others). Mitchell defines this attribute as “an unwillingness to make concessions or to negotiate in a manner that involves mutual consideration for the interests of all parties.”1

When they make a show of negotiating, “self-interest is always at the core of their decision-making, and any concessions or ‘goodness’ have an underlying motive.”

“Compromises are always strategic and might include faking good and demonising the other person or it might be exceptionally litigious.” (Category 4ii)

“When you are provided with new information, you revise. They do not. You can engage in a long dialogue about all the reasons why they should compromise but they have an unwillingness which is steadfast.” (Category 4i)

It was explained by several participants that this attribute is often hidden by a ‘façade’ adopted by a person of DP that may be one of, for example, shyness, gentleness, humbleness, or ‘goofiness’ … The findings show that regardless of the façade, the person of DP has a relentless willingness to maintain pursuit of their goal, way beyond when people not of DP would give up, including those who are exceptionally determined. A way of describing this phenomenon created by the thesis author and based on the data is ‘unrelenting attention to personal purpose.’

This is what we’re up against.

Next up: more PPP attributes.

Sounds like American foreign policy!

Exactly. No one believes the victim of this type of person. Thus, exacerbating the torture and increasing the isolation of a victim.

Harrison, Excellent series from what I’ve seen thus far. Because of other commitments at present I haven’t quite managed to take it all in. To that end in fact I’ll be revisiting each instalment again soon as the series as a whole relates to several projects I'm presently working on. I was particularly taken with the example provided of the estimable Lyndon Baines Johnson (aka LBJ), a man whose personality pathologies I’m very familiar with. I was a good friend of Philip Nelson, the author of what many consider to be the definitive insight into those “pathologies”, and like yourself he was a guest on my TNT radio show when it was running. (Sadly Phil passed away last year). LBJ is without doubt one of the archetypal poster boys of the PPP personality. For readers interested in Mr Nelson’s work, here’s a link. 👀👉 https://lbjthemasterofdeceit.com